Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

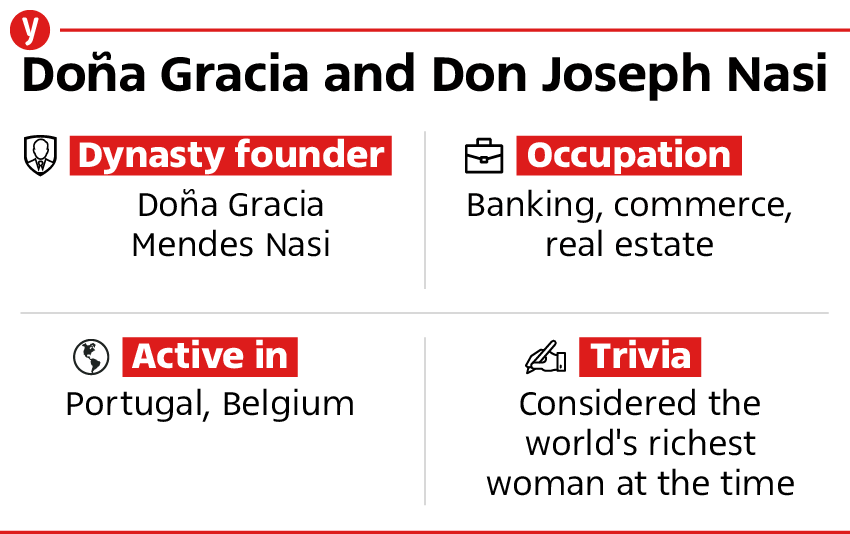

A precursor to Zionism, predating Theodor Herzl by 330 years, she saved thousands of Jews. Doña Gracia (Hannah) Nasi was a Jewish woman who directly challenged the pope. And she was the richest woman on Earth.

This widow who became a leader, was one of the most central and senior Jewish figures in recent centuries. But she’s virtually unknown to the average Israeli – she doesn’t even have a street named after her.

Irit Ahdoot, curator of the museum named in her honor in Tiberias, stresses that these accolades are neither spin, myths nor folktales. Doña Gracia’s story has been researched by leading historians and the details of her life are supported by documentary evidence.

The secret that changed her life

In 1510, just under 80 years after the expulsion of the Jews from the country, Beatrice da Luna-Gracia (Hanna) Nasi was born in Lisbon, Portugal. Her father, Álvaro de Luna, was a doctor and her mother, Felipa, hailed from the wealthy Benveniste family. Her family had always been Jewish community leaders – earning them the name “Nasi” (prince). At the end of the 15th century, like many of her fellow Jews, Felipa was forced to, at least publicly, convert to Christianity.

At the age of 12, Gracia was taken into a secret basement in the family home where her mother told her about her background and taught her Torah and mitzvot. Although not uncommon among Jewish children in Portugal at the time, it made a great impression on young Gracia, forging a potent Jewish sense of identity that, in time, would have great impact on the Jewish world.

In that cellar, when she was 18, in a secret Jewish ceremony, she married her uncle, Francisco Mendes, (Hebrew name: Zemach Benveniste). They also conducted a grand ceremony in Lisbon Cathedral with prominent dignitaries in attendance.

Mendes, who was significantly older than his wife, was considered a financial genius: An international merchant, best known for trading black pepper, he managed a bank in Portugal while his brother, Diogo managed the Antwerp branch. The Mendes-Benveniste family ranked among the richest in Portugal. Gracia loved and respected her husband. They had one daughter, Reyna. Their joy knew no bounds.

Sadly, only eight years into their marriage, Francisco died, leaving Gracia alone, aged just 26. The beautiful young widow chose to never remarry. She fulfilled her husband’s dying wishes of reinterring his remains, from a church cemetery in Lisbon, to Jerusalem’s Mount of Olives. Her own burial site is unknown to this day.

The richest woman in her time

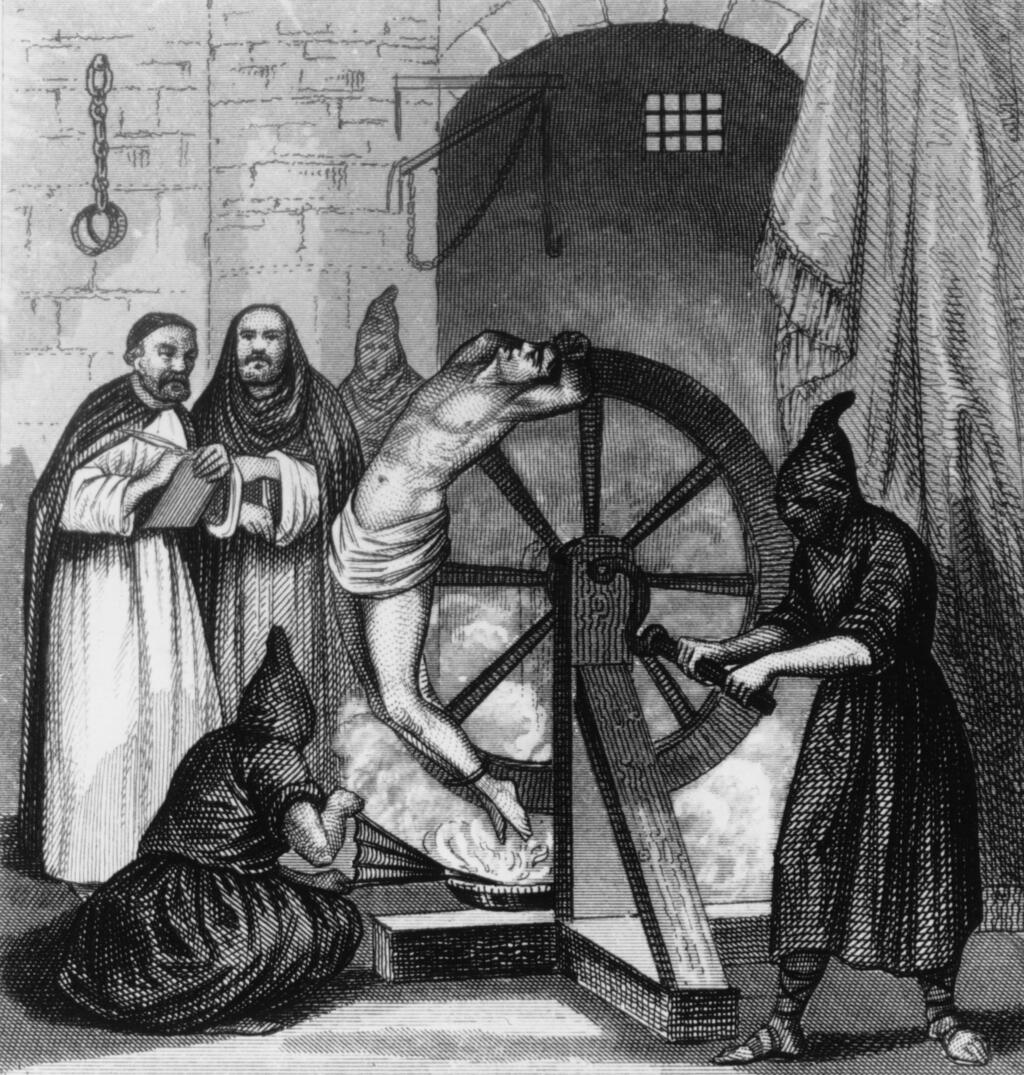

Her husband’s death was followed by events that rocked the Jewish world: The Inquisition made its way to Portugal, and the horrific execution of Conversos became an everyday occurrence. Gracia realized she had to flee the country.

8 View gallery

A medallion left by the family. Mistakenly identified with Dona Gracia, but created in honor of her daughter's betrothal

She gradually and skillfully relocated the family businesses to Antwerp. She, herself, then left Lisbon for Belgium where she was reunited with her brother-in-law, Diogo, who she had married to her younger sister, Brianda de Luna - a move almost leading to her own undoing.

The young widow firmly managed her banking, trading, property, and maritime businesses. She lived in grand palaces served by an army of servants while trading with not only the world’s greatest merchants, but also rulers and international key figures.

She then proceeded to marry off her daughter, Reyna to her nephew, Don Joseph - a man who would become one of the richest and most influential people throughout the Ottoman Empire. Scholars say that Doña Gracia was not only the richest Jewish woman in the world, but the richest woman in the world altogether - the 16th century Elon Musk was a Jewish woman.

She then proceeded to marry off her daughter, Reyna to her nephew, Don Joseph - a man who would become one of the richest and most influential people throughout the Ottoman Empire

Volumes have been written researching the work she conducted for her fellow Jews: She translated the Hebrew Bible into Ladino, founded scores of synagogues throughout the empire and supported countless families.

In this article, we will focus on two of her many activities. As mentioned above, she rejoined her brother-in-law, Diogo, in Antwerp, had him married to her sister, and together they ran the family businesses. The two however conducted further, clandestine, activities: settling Jews fleeing the Inquisition in neutral countries across the globe.

Headbutting with the pope

Michal Aharoni-Regev, who has penned a historical novel “Doña Gracia’s Gold Pendant,” explains: “Imagine you’re living in Portugal in constant fear that you’ll be killed by the Inquisition and you’re trying to flee. How would you do that? You have two chickens in your yard, two cows and a little metal workshop. Leaving behind your meager property and emigrating to the unknown would invariably spell certain death. Doña Gracia would send her agents with promissory notes to the value of the property.

"Then, using a long succession of bribes to inn-keepers, monasteries, port personnel, ship workers and captains, she’d smuggle Jews to safer places including Salonika, Tunisia, Morocco, Russia, Brazil and the Caribbean.”

8 View gallery

Michal Aharoni-Regev in a performance in memory of Donna Gracia Nasih

(Photo: Michal Sabag)

Doña Gracia’s agents were also ready and waiting at these destinations. They were tasked with receiving the promissory notes from hundreds of the thousands of exiles, granting them the full monetary value of the property. The refugees would thus be no burden to the local community and would have the chance to prosper.

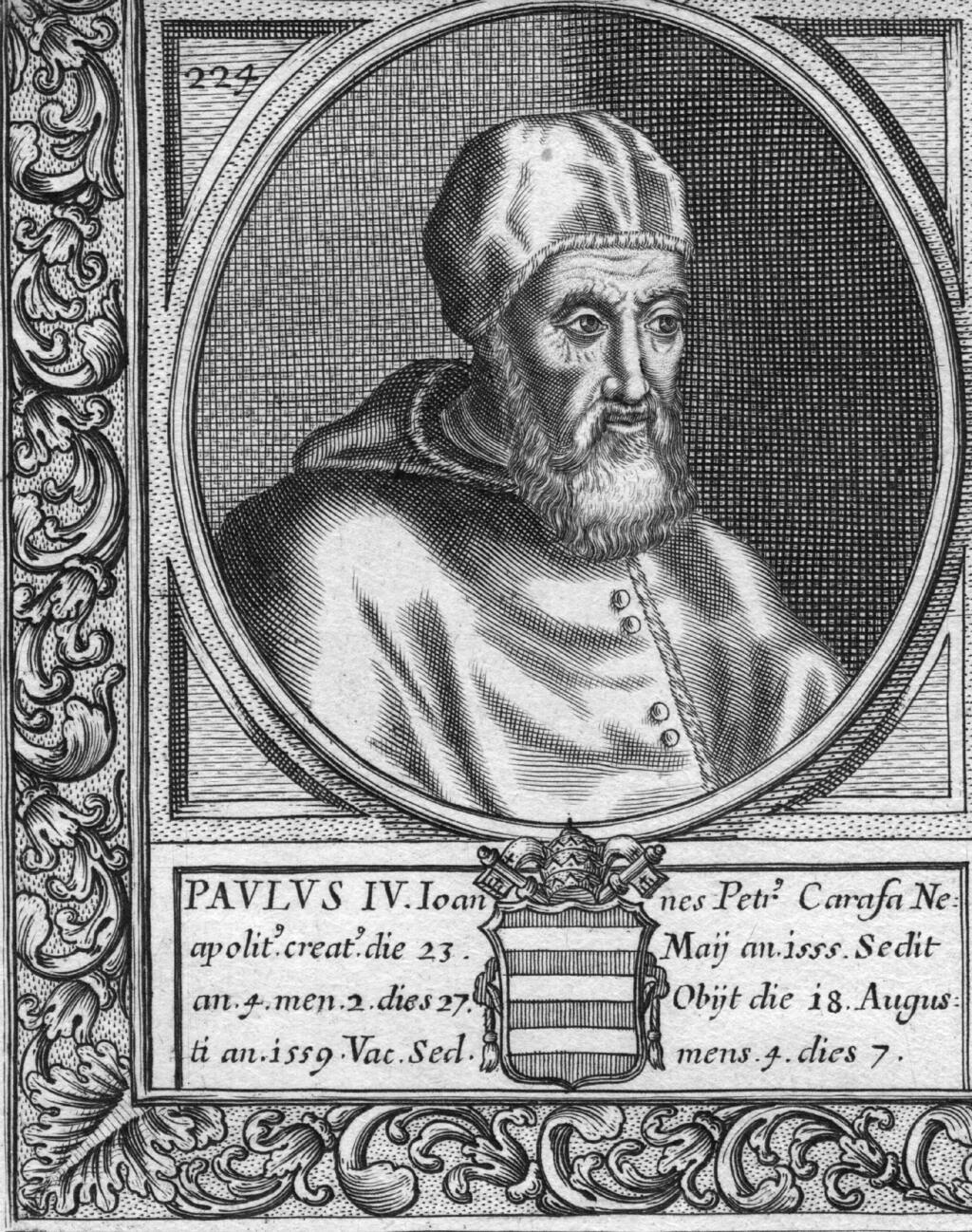

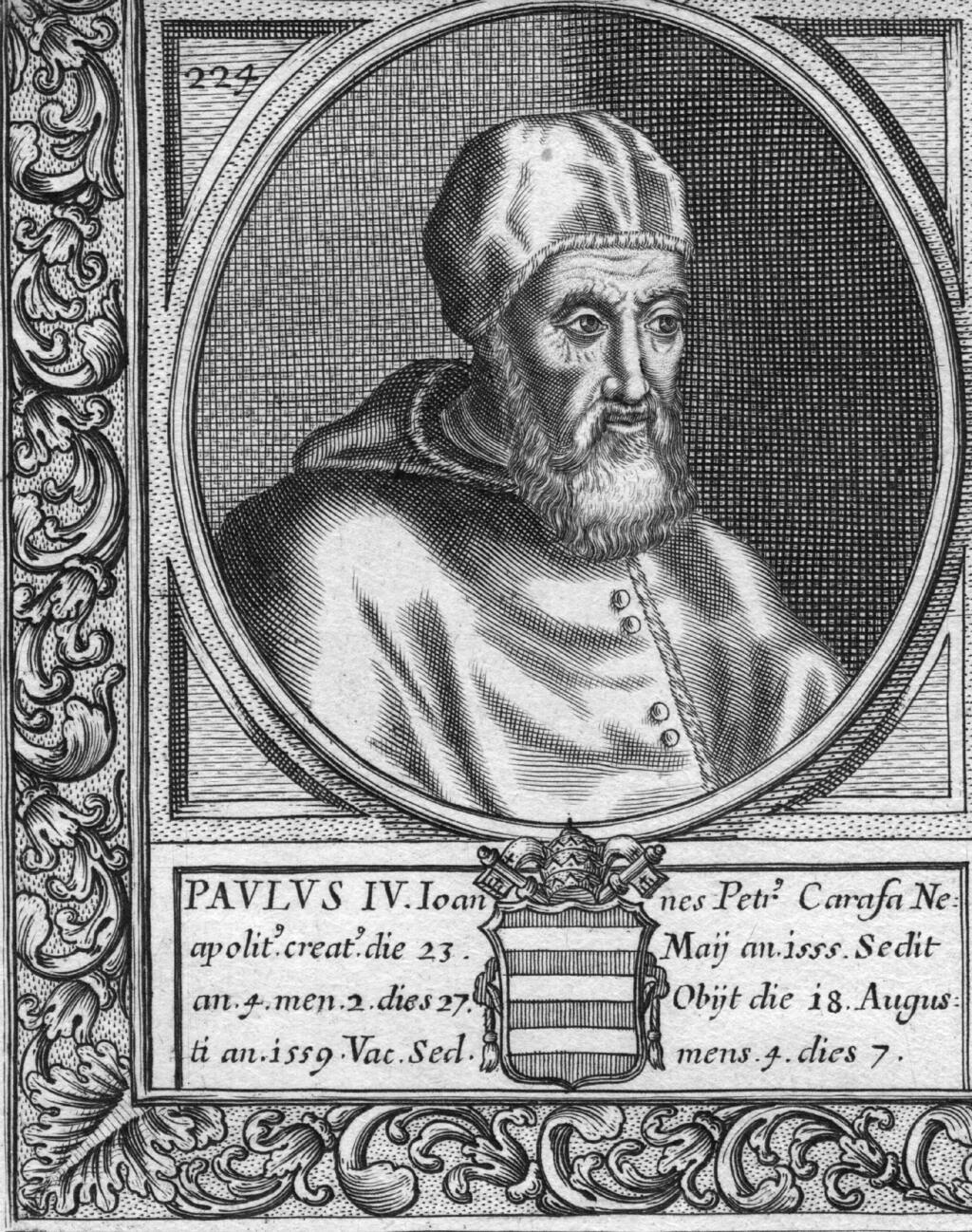

Doña Gracia's great wealth and phenomenal connections made her one of the most influential “statesmen” of the Ottoman Empire. Sulieman the Magnificent included her in diplomatic negotiations at the highest levels. One, almost surrealistic, episode was when she directly challenged Pope Paul IV, leader of the Christian world.

“At a time when most women were illiterate, didn’t hold positions and weren’t expected to have opinions, after 1,500 years of exile, a Jewish woman arose and challenged one of the most powerful people in the world," says Aharoni-Regev.

The Jewish boycott

Pope Paul IV, an avowed Jew-hater, had sentenced a group of Jews in Ancona, Italy to be imprisoned and burnt at the stake. After a confrontation with the sultan, the pope eventually had 24 Jews who refused to surrender their faith burnt in the town square. This was not unusual during the Inquisition. What the pope didn’t see coming was the sheer force of Doña Gracia and her nephew and son-in-law, Don Joseph.

The duo declared a boycott on the port of Ancona. They announced that their numerous ships wouldn’t be disembarking in Ancona, but rather would be redirected to the port of Pesaro. Maritime activity at Ancona decreased, even coming to a halt, causing the city enormous financial loss.

“Doña Gracia decided that Jews keeping their heads down had to come to an end,” Irit Ahdoot tells us. “She assembled the richest men of Ancona and declared a boycott on the pope’s private property. Ancona was bankrupt.”

8 View gallery

A painting of Pope Paul IV. Challenging one of the most powerful men in the world at the time

(Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

The Jewish boycott rocked the world. Everyone was talking about it. Numerous rabbis supported the daring step, but many Jews in Ancona, fearing for their own livelihoods, were against it. The pope promised incentives and benefits to the city’s merchants and the boycott gradually died down.

A few months later, as the boycott came to an end, ships started harboring at Ancona once again. This international incident implemented by a female leader, contending with both the all-powerful leader of the Christian world and the local Jewish community fearing its consequences, gives us an insight into the pure strength of this remarkable woman.

A rift between sisters

We would be remiss discussing Doña Gracia without mentioning one of the most painful events of her life: Her conflict with her own sister, Brianda - a rift that almost led to catastrophe. As mentioned above, Brianda was married to her uncle, Diogo. Together, they led a happy life of luxury. Upon Diogo’s death, he left his vast fortune, along with control of his bank, to his sister-in-law Doña Gracia.

Aharoni-Regev believes that two factors stood behind this decision: Firstly, the lion’s share of the fortune was the fruit of the labor of his brother, Doña Gracia’s late husband, Francisco Mendes. Secondly: The understanding that his sister-in-law would use the money to continue rescuing Jews – something that could not ring true about his wife, Brianda.

8 View gallery

Michal Aharoni-Regev at a performance in memory of Doña Gracia Nasi

(Photo: Michal Sabag)

Doña Gracia was living with her sister in Venice. Formally, she conducted herself as a Christian. In private, however, Gracia carried on keeping mitzvot and she continued her clandestine work of helping the Jewish people. At some stage, she felt the ground burning beneath her feet and that her Judaism would be exposed. She started leaving Venice for the more liberal and inclusive Duchy of Ferrara.

Brianda, on the other hand, wanting to carry on living the good life in Venice, was overcome with rage. Compounded by their anger about her husband’s will, she turned in her sister to the authorities, reporting her as a secret Jew. Doña Gracia was immediately arrested, only to be released following Don Joseph’s intervention.

Attempt to establish a ‘Jewish State’

This episode, described on the “Ishei Rechov” (Street Names) website, ends up with Doña Gracia’s moving to Ferrara, finally announcing publicly that she is Jewish. In Ferrara, she carried on helping Jews and reconciled with her sister when the latter also eventually made the move to Ferrara.

The controversy regarding the identity of the first forerunners of Zionism, from the great rabbis Kalisher and Alkalai, through to Moshe Hess and later Herzl, generally omits Doña Gracia, the woman who lived centuries before these prominent individuals.

"Her final resting place was deliberately made to disappear. There was a fear that Gracia’s greatness would elevate her to a special, holy status, that of a False Messiah and that pilgrimage to her gravesite would turn into a cult of its own"

Like Herzl, Doña Gracia and Don Joseph understood that the solution to the suffering of the Jewish People was founding a Jewish settlement in the Land of Israel or, as Natan Shor, Land of Israel scholar, puts it: “It was the first attempt to establish a ‘Jewish State’ on the shores of the Kinneret’.”

They approached the sultan to obtain a “kushan” (Ottoman land deed) in the region. They prove unsuccessful in procuring such a deed for the holy city of Jerusalem, but they did manage to lease land in the holy city of Tiberias.

Doña Gracia and her son-in-law sent money to the region, built homes, inaugurated a synagogue, and start building a wall around the developing city.

As denoted in “Ishei Rechov,” history repeats itself. The Arab laborers constructing the wall refused to accept the new “Jewish State” program, went on strike and began an uprising. Building the wall came to a halt. Don Joseph complained to the pasha in Damascus who sent military forces to suppress the rebellion. The two rebel leaders were hanged and the laborers got back to building the wall.

Did the Jews fulfill Doña Gracia’s dreams?

The answer has to be no. Now aged 50, an advanced age for the day, Doña Gracia’s strength was flagging. The Jews did not respond enthusiastically to her calls. “Jabotinsky said ‘You can take the Jew out of the Diaspora, but you can’t take the Diaspora out of the Jew’” Aharoni-Regev says. “The Jews found it hard to leave behind everything and come to the Land of Israel. They were tired of their wonderings and were accustomed to their lives in exile.“

Following Doña Gracia’s death in 1569, a letter was sent to all Jewish communities, asking them to keep seven days’ mourning in her memory. “There are two women in Jewish historiography who were bitterly mourned: Miriam, the sister of Moses, who died in the desert; and Doña Gracia, who died in Istanbul," says Irit Ahdoot. She further explains that all the property of Doña Gracia and Don Joseph disappeared after their deaths, the authorities taking control of it.

Following Doña Gracia’s death in 1569, a letter was sent to all Jewish communities, asking them to keep seven days’ mourning in her memory

Surprisingly, no one knows. Ahdoot has her own explanation: “Her final resting place was deliberately made to disappear. There was a fear that Gracia’s greatness would elevate her to a special, holy status, that of a False Messiah and that pilgrimage to her gravesite would turn into a cult of its own.“

Although Gracia lived to 59, considered advanced at the time, Ahdoot proposes she may have been poisoned: In the period leading up to her death, she traveled extensively proving that she was strong and healthy. Ahdoot believes that Pope Paul IV, who suffered great defeats at the hands of Gracia, was responsible for her death.

The stumbling block for nationwide recognition

Sadly, this formidable woman never made it into the Israeli collective memory. Ahdoot believes that being a woman of Sephardic background was the stumbling block. “History is written by men who play down women’s contributions, however great they may be.”

We have no portrait of Gracia. There is an image engraved on a family medallion that has been misattributed to Gracia. It turns out that it was fashioned on the occasion of the engagement Brianda’s daughter, Gracia La Chica, named as such to distinguish her from her great aunt. Two such medallions are on display in museums in Rome and New York.

It’s almost impossible to know. In his autobiography, the Italian Jewish doctor and general, Guido Aaron Mendes (died 1965; his grandson, international orthopedic surgeon, 86-year-old Prof. David Giorgio Mendes-Nasi lives in Israel) claims descent from Doña Gracia. Ahdoot and Aharoni both reject the claim as Doña Gracia’s daughter, Reyna, and her husband Don Joseph were childless.

Although Reyna’s niece, Gracia La Chica, did produce descendants, it would be near impossible to find them. Ahdoot and Aharoni-Regev say that the name Mendes is as common in South America as the name Cohen is in Israel. Hundreds of thousands, possibly millions, of Jews over the centuries have been called Mendes - a name adopted to better integrate into Christian society. It’s hard to say which ones are descended from Gracia La Chica.

Both Irit Ahdoot and Michal Aharoni-Regev are keen to convey to us that this great Jewish leader should not only be researched, but she should be lived - that her story should be studied in Israeli schools, that she be memorialized on the country’s sites and streets.