Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

As the IDF navigates various challenges, Israeli and international produce fills the Gaza-side warehouses of the Kerem Shalom crossing, en route to Palestinians in the coastal enclave. Peaches from Yesud HaMa'ala near the Lebanese border, premium bananas from Hof HaCarmel orchards and apricots from Zichron Ya’akov represent a fraction of the aid being transported. Israel’s humanitarian assistance to Gaza has reached new heights, including trucks laden with fruits, vegetables, gas and fuel.

IDF commanders implementing government directives understand that within hours, these supplies will reach Hamas food and energy depots in displaced persons shelters. Forklift operators in Khan Younis report that the Kerem Shalom crossing is beginning to resemble its pre-war state, with supply highways opened by Israel into Gaza.

In the absence of Israeli martial law or the Palestinian Authority to distribute food and supplies to civilians, the military knows Hamas will seize these consumer goods, deep into the ninth month of fighting. Some truck windows are shielded with iron grilles to prevent looting or disorder on their routes.

The 12th Reserve Infantry Brigade, securing Rafah’s eastern sector near the border, has adapted to these aid truck hijacking attempts, often by gunmen from smaller terrorist groups or criminals challenging Hamas. Drones and UAVs escort the trucks, while IDF snipers lie in wait at intersections. When armed groups are identified, the forces eliminate them from the air or ground, allowing the trucks to proceed. Six gunmen were eliminated in broad daylight last week.

The chaos in areas of Gaza where Hamas has not yet reestablished control and the IDF has withdrawn is so severe that Israeli forces have been shocked to witness street battles among armed Gaza factions over aid trucks in the past two weeks, even before Hamas can seize them.

Before setting out, commanders on the ground express frustration with the politicians' recent criticisms of the IDF, particularly from government members and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who have ordered a dramatic increase in aid to Gazans. The humanitarian corridor, which is granted immunity from gunfire, lies in an open, sandy expanse between the Kerem Shalom crossing and the main north-south road in Gaza, leading to Khan Younis and Gaza City.

Due to the IDF's full control over the area between Rafah, where fighting continues, and the Kerem Shalom crossing, the IDF spokesperson announced a daily humanitarian cease-fire in this corridor from 7:00 a.m. to 9:00 p.m. to assure international aid organizations of safe passage for supplies to Gaza’s civilians.

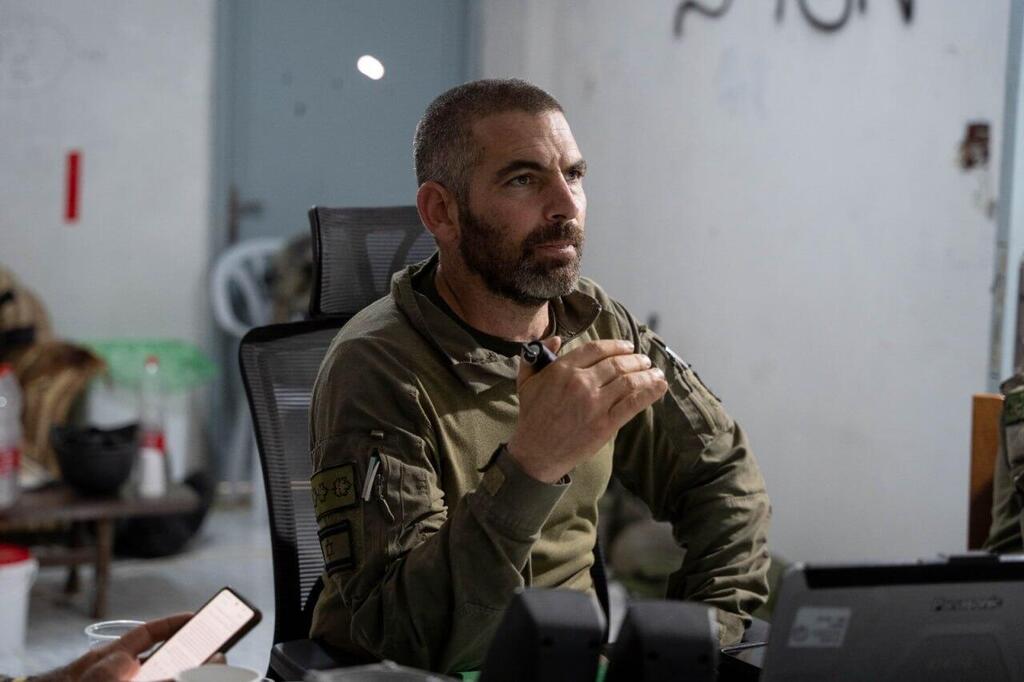

“These are two entirely separate issues,” explains 12th Brigade Commander Colonel Avri Elbaz, from a low hill near the Philadelphi Corridor, which stretches the Gaza-Egypt border.

“In Rafah, we haven’t stopped for a moment, and on this corridor, we attack at night when necessary, targeting enemies but not the trucks themselves. I caution my soldiers against turning this into a static operation like in the West Bank. Delivering humanitarian aid is our mission, but this is still a combat zone. The situation here is dynamic, and we must not get used to static scenarios like checkpoints in the West Bank.

“There’s no treading in place here. We must remember we are always prepared for unexpected hostage situations and move cautiously in areas where we suspect captives are held in Rafah, to avoid endangering them.”

The Egyptian flag waves proudly on the other side of the Rafah crossing. A large complex of warehouses, terminals and two-story office buildings — most of these structures are damaged or burned to a crisp from the IDF's takeover at the beginning of the operation.

Inside the compound, IDF forces have erected tall concrete walls, some exceeding 50 feet, as part of their defensive measures. Egyptian soldiers are not visible, but their observation equipment is noticeable atop yellow masts overlooking the area. Following the orders of their commanders, Egyptian soldiers have been moved several hundred yards south after an incident last month in which an Egyptian soldier was killed by IDF fire.

Egypt’s conduct here is perplexing: on one hand, there is full coordination with Israel before and during the war, despite Cairo's public political condemnations. On the other hand, Egypt has long turned a blind eye to Hamas' armament, allowing tens of thousands of weapons to flow into the territory.

According to reports, Egypt permitted Hamas to place hundreds of rocket launchers along the border with Sinai, aimed at Be'er Sheba and fired at Tel Aviv without hindrance. Egypt also allowed trucks to deliver various weapons daily into Gaza, not just through the extensive underground smuggling tunnels. In this sense, Egypt has played a double game with Israel and Hamas, regardless of the ruling regime in Cairo.

The work of locating tunnels here is meticulous and slow, often without intelligence, covering small sectors one at a time with giant drills and bulldozers searching every reported line for Hamas' so-called "metro" network, which was their lifeline.

A month and a half into the Rafah operation, commanders push back against criticism of a standstill, even within the IDF. There is a significant gap between the political echelon's perspective of Rafah as Hamas’ last and toughest stronghold and the reality on the ground. Five brigades are currently fighting here, slightly fewer than at the operation's peak, and the four local Hamas battalions are not much different from other Hamas battalions encountered throughout Gaza.

"Rafah Brigade is seasoned and known for its booby-trapping capabilities. It’s the 'demolition brigade' that has rigged many buildings and tunnels, so we operate here wisely and cautiously, even if it seems slow, to ensure the safety of our forces," agree Colonel Elbaz and his counterpart in northwest Rafah, Nahal Brigade Commander Colonel Yair Zuckerman.

In the eighth week of the Rafah operation, the IDF has identified 25 tunnel entrances along the Philadelphi Corridor, stretching over 9 miles from the Tel al-Sultan neighborhood on Gaza's southernmost coastline to the Israeli border near Kibbutz Kerem Shalom.

In the seven months leading up to the IDF's arrival in Rafah, after delays imposed by the political echelon, the local Hamas brigade had learned from past encounters. Numerous explosives, some of types previously unseen by commanders and soldiers elsewhere in Gaza, are hidden in branching tunnels and deep shafts. It will take more time to secure and destroy the 25 tunnels found so far and to locate the rest.

"This will continue for at least another six months, requiring our constant presence on the Philadelphi Corridor, as it is a slow and complex operation," describe the senior commanders of the operation.

"In the Netzarim Corridor, which is about half the length of the Philadelphi Corridor, it took us more than three months to locate and destroy 12 kilometers (7.5 miles) of tunnels beneath the corridor separating Gaza City from central and southern Gaza," they emphasized. Colonel Elbaz added, "Hamas has adopted Viet Cong tactics here, with slow and hidden combat from tunnels and bunkers to try and draw us in for a prolonged conflict."

Therefore, it can be cautiously estimated that the Philadelphi Corridor will soon resemble the Naetzarim Corridor: permanent IDF outposts, constant presence and raids into adjacent Rafah neighborhoods to deepen the impact on Hamas. The "day after" question concerns the mechanism to end the prolonged fighting, which some estimates suggest will continue for at least another two years.

Will Egypt agree and will the U.S. fund billions of dollars for Israel's initiative to construct an underground barrier against tunnels along the Philadelphi Corridor, similar to the one along the Israel-Gaza border?

Even simpler issues, such as deploying non-Hamas-affiliated Palestinian police to operate the Rafah crossing, remain unresolved. "Holding the Netzarim Corridor for three months earlier this year proved to me, militarily and professionally, how critical it will be to maintain control over the Philadelphi Corridor to complete our missions here," emphasized Nahal Brigade Commander Colonel Zuckerman.

We have crossed more than half of the Philadelphi Corridor, and the IDF's operational control is complete. We did not see tanks or Namer APCs on the route, as they are mainly engaged in urban areas. Here, lighter forces are primarily in action. Movement was swift, with open Hummers on the way in and the highly agile Eitan APCs on the way back. Thousands of Gazans have already returned to the neighborhoods that the IDF has captured in Rafah, and commanders report no significant resistance from the local Hamas brigade.

The intensified operation in the heart of the urban area may conclude soon. Some brigades that will withdraw are preparing for a potential broad confrontation with Hezbollah, and the military will transition to the so-called "third phase" of the war, involving recurrent raids, including in Rafah.

Meanwhile, reports from Gaza on Thursday indicated that the IDF conducted a surprise raid on the Shijaiyah neighborhood in Gaza City, with many residents fleeing the area. This followed an appeal by IDF Arabic spokesperson Lt. Col. Avichay Adraee, urging residents to "immediately evacuate south along Salah al-Din Street to the humanitarian zone."

Last week, IDF Chief of Staff Lt. Gen. Herzi Halevi visited Rafah again and received backing from the brigade commanders regarding ammunition management, despite delays in arms shipments from the U.S. and the possibility of a full-scale war in the north.

"Do you have a dilemma about resource allocation? Take the heavy barrage bombs to the north; we'll manage here with what we have," one of the brigade commanders told the army chief. "Hamas here is already significantly weakened, a fairly fragmented guerrilla group."

Some brigade commanders are still grappling with the shock of the initial blow Hamas managed to deliver to Israel on October 7. "It was one of the best commando raids in military history. We never thought this could happen," they said.

They told the army chief to also consider "the cornerstone: the human element," as a critical component of military doctrine. The 12th Brigade, for example, was not supposed to be here at all, and the operation in Rafah was initially planned to include two regular divisions to be more decisive and swift. However, due to Cabinet constraints, the mission was ultimately assigned only to the 162nd Division with a different composition than originally planned.

Current IDF teams consist of 8-12 fighters, down from the 16-18 seen in the recent past. Reserve force turnout in Rafah is around 80%, down from 100% or more during the first four months of the war. Additionally, a small percentage of regular soldiers have been withdrawn due to mental health issues.

"We manage our ammunition and human resources efficiently. Naturally, there's wear and tear, but it's dynamic. During intense mission periods, we bring in more personnel and release them for breaks during calmer days," described Colonel Elbaz.

"Destroying Hamas? The level of satisfaction matches the expectations. It's like removing a car’s spark plug – it will certainly immobilize it, but it will still be there. So, it will take a long time, but we can handle it," he added.

Nahal Brigade Commander Colonel Zuckerman spoke about the rotation within his forces, one of the few fighting continuously since the outset of ground operations in late October. "In the Rafah operation, I always have one battalion out for a break to refresh and improve readiness; currently, it's our reconnaissance unit."

Of the approximately 3,000 members of the local Hamas brigade, IDF forces have killed or injured about 700 fighters so far, according to the 162nd Division's estimates. The rest have fled north, mainly to nearby Khan Younis, or remain as small guerrilla cells, lurking in tunnels and consisting of no more than three or four fighters. The local Hamas battalion in the area deploys anti-tank ambushes, snipers and explosives with remote surveillance cameras in every major neighborhood.

"We have defeated the battalions in the neighborhoods of Shabura, Yibna, Brazil and M.P.K., with the last remaining one being the northwest battalion in Tel al-Sultan, currently being handled by the 401st Brigade," say sources in the 162nd Division. "There are areas in Rafah we haven't entered yet, like the northern outskirts of the city."

Lieutenant Colonel Oz Mualem, commander of Nahal's 931st Battalion, gave his troops a seemingly simple task at the start of the operation: find the first tunnel within 24 hours.

"We have entered the land of tunnels," he explained. "There are tunnels 360 degrees around us, in all directions and at different depths underground. If you're not careful, you'll advance and get hit from a hidden shaft you missed. My soldiers not only quickly found the first tunnel but also managed to kill the terrorists inside using special means.

"There is an enormous amount of explosive vests and IEDs here that we didn't see in Shati or Jabaliya, so we're not rushing like we did there to avoid endangering the soldiers. It's frustrating to return to a place you've fought in and suddenly encounter a new minefield, but that's why we're doing this smartly, based on our experience."

His commander, Colonel Zuckerman, agreed. "Those who exaggerated the story of Rafah probably didn't want us to get here. Hamas' center of gravity here is the tunnels. They are very intricate, but we will get to them. The enemy isn't waiting for us, but their booby-trapped houses are."