Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

"The people have spoken!” one of the more famous quotes in modern politics was first said by Alain Juppe after his electoral defeat in France 97.

Related stories:

“The people have spoken. Their decision is sovereign. We all respect it... I wish good luck to those who will now govern France."

It has since been recycled albeit with less acclaim, by Clinton, Obama and Trump in turn and in different political contexts, but with the same democratic sentiment; citizens wield the power of their own destiny and country’s policy at the ballot box.

But ask anybody in Israel if they can imagine any MK in the Israeli political arena fresh off an electoral defeat uttering similar words, and they will understandably scoff.

When given an inch, will take a mile

Israelis are not good at losing in politics. Much like their beloved football, on an international level, a loss is just a loss, we are used to it. But domestically? Hell no! This is particularly true of the left wing, who should be used to it by now but perhaps their stronghold on every social and national institution from the army and police to the in-focus judiciary, allows them to continue to refuse to concede nobly in the political arena.

But for the life of me, I cannot understand why the democratic blueprint for the state does not allow for popular citizen referendum votes on mammoth matters other than territorial withdrawals.

Perhaps, because it’s hard to avoid the reality that recent demonstrations have proven Israeli citizens when given an inch, will take a mile, all the way down the Ayalon Highway.

I cannot understand why the democratic blueprint for the state does not allow for popular citizen referendum votes on mammoth matters other than territorial withdrawals.

It’s not beyond imagination to foresee independent groups of the Israeli public with special interests calling for referendums at the drop of a hat, and over even the most menial issues. A good example would be the freshly passed ‘Leven law’ (which allows for hospital directors to hang signs on the premises forbidding Hametz on-site during Passover), which the military refuseniks groups have already stated their intentions to break in a letter written in the immediate aftermath of the coalitions responsible announcement to pause a third and final reading of the judicial reform pending de-escalation talks in search of compromise. Maybe.

Last round of elections - referendum

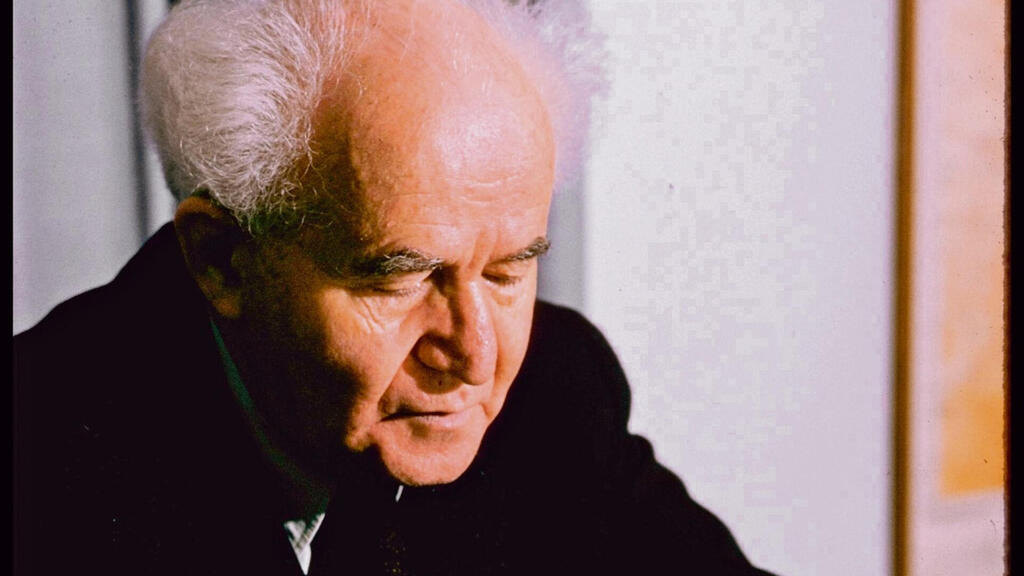

It is not as though it’s never been proposed. Ben-Gurion tried introducing referendums in 1958 to shut up the Religious Zionist party (NRP). Begin also gave it a go, only this time trying to make it a broad law that 100k citizens can halt any law pending a referendum (see my fear above). More recently, Ariel Sharon shot down calls for a referendum over Israel’s legally contentious withdrawal from Gaza.

Ironically, the only form of referendum law to be passed to date, was by Prime Minister Netanyahu's cabinet with a slim majority in 2013, in regard to decisions to withdraw from Israeli-held territory. The same law was effectively ignored by Yair Lapid when he signed the recent territorial waters agreement with Lebanon. This was not a treaty, by any means, but apparently, the High Court saw no reason to intervene and gave him a pass.

The closest Israel has come in recent history to a popular referendum vote is the last round of elections. These were universally understood to be a referendum on the political future of Netanyahu himself. The latest round of these included the number one issue on the table from the perspective of the right, Judicial reform.

International media got it

Commentary in the international media was a consensus of surprisingly accurate reporting and astute understanding that these elections were above all else, a referendum on Israel’s Leader in Chief.

“As Israelis prepare to go to the polls this week to choose their next Knesset (parliament), it is striking what this election is, and what it is decidedly not, about. Daniel B. Shapiro of CNN broke it down in all its simplicity.

"It’s not about security. A broad consensus prevails on policies that might address the challenges posed by Iran, Syria and Hezbollah. It’s not about the economy. People have their bread-and-butter complaints, but the Israeli economy continues its impressive growth, outperforming most Western economies over the last decade. It’s certainly not about the Palestinians. …No, the election is about one thing, and one thing only: Prime Minister Benjamin (Bibi) Netanyahu.”

The Wall Street Journal and CBC and even the Guardian made the same correct observation.

Fast forward 4 election cycles… and Bibi is still at the helm and as far as referendums go, that is about as definitive as it gets, with the possible exception of having simple a YES or NO checkbox under the question "are you fed up with Bibi yet?” on the ballot slip.

The same law was effectively ignored by Yair Lapid when he signed the territorial waters agreement with Lebanon. This was not a treaty, by any means, but apparently, the High Court saw no reason to intervene

Actually, going back only as recently as 1996-2001, citizens had the option to do exactly that. One vote for the party and one for the prime minister was they way things were done for a while.

The unavoidable irony is, that it was Ariel Sharon’s (initial) right-wing government in 2003 that enacted the law to get rid of the previous separate election for prime minister, and the post was returned to the leader of the party successfully forming a coalition government.

So much for that.

In another part of the world

But it did get me thinking about recent referendums I did get to vote in, in another part of the world similarly undergoing one political earthquake after tsunami in recent years and draw some interesting comparisons and conclusions. These took place in the United Kingdom, or ‘United’ at least for the time being still.

First, was the Scottish Independence Referendum in 2014 where the good people of Scotland (from where I hail myself) voted to stay part of the union with England, Wales, and N. Ireland.

A year later the SNP (Scottish nationalist Part) won the local elections for the first time taking 95% of the government seats up for grabs and thus the largest majority enjoyed in any country by a single political party during peacetime ever (I think!).

Go figure. A referendum defeat to the anti-independence campaign known as “Stay” while apparently having 95% support flattening the opposition albeit a year later. Obviously, many factors contributed to the referendum outcome, but here are two takeaways for me at the time.

The first, is that there are matters of state which simply do not succumb to party loyalty. This is simple enough to understand and in the context of Israeli politics would lend some credibility to the logic of those arguing that judicial reform is not a matter of binary right- or left-wing politics.

This lends credibility in turn to the right-wing argument that fear-mongering is handicapping the majority's desire for meaningful judicial reform.

My second realization fundamentally changed the way I approached my own voting, going forward and it goes something like this. Wishing for something is not the same as wanting it. Or, in other words, as the saying goes “be careful what you wish for”.

Let me explain. If you were to canvas ordinary Scottish citizens today (‘canvas’ being the British political equivalent to a startup's investment ‘Pitch’), a guaranteed utopian Scottish independent state, thriving, wealthy and successful, you would be hard-pressed to find any ‘Stay’ votes.

But the reality is that fear of political and social consequences often overrides our real desires. Wishing for an outcome is not the same as having the drive to implement it. You can wish for your country’s independence but stop short and shy away from the journey it takes to gain it, opting for a safer status quo. This is translated to a ‘Stay’ vote but was far from being an ‘anti-independence’ vote.

Again, in the context of current Israeli affairs, this lends credibility in turn to the right-wing argument that fear-mongering is handicapping the majority's desire for meaningful judicial reform.

The high court will never allow a referendum

This takes me to the second referendum I voted in, Brexit, where the same forces were at play albeit with vastly contrasting outcomes. This time, the desire for independence from the EU was strong enough to overcome the fear of any consequences. If anybody who voted in that referendum denies feeling any apprehension about the day after, they would be lying. But Self-confidence and belief were strong, and the desire to fight was there.

David Cameron’s elected government was staunchly against breaking the EU partnership yet lost that referendum and while the SNP’s local election’s entire mandate was a Scottish Independence white paper, they lost their referendum also.

Of particular interest to anyone wishing to compare the behavior of Israel’s high court to that of other western democracies, is that both the SNP and the Conservative party were allowed to use their government funds to distribute material explaining their own and position viewpoints and positions in a democratic display of engaging the country to exercise their voting right.

A basic right not afforded to the current Israeli government by the High court that both muzzled the prime minister from discussing the matter and bolted the coffers of the Hasbara office firmly shut. Something which recently came to light, when Hasbara mister Galit Distal was challenged as to why the government’s own narrative was so poor in comparison to the opposition, by the popular journalist Ayala Hasson on prime-time TV.

Either way, the concluding story is of two governments, voted in by the people, who lost two referendums voted in by the people. With all this in mind and circling back to Israel again, we should probably be asking a few questions.

Namely, does having 64 mandate majority right-wing coalition automatically prove that most citizens are pro-judicial reform in its current state? And, would it not be logical to hold a popular referendum on the matter?

And then, will an Israeli popular referendum even prove definitive, or will the fear factor demoralize the voters' desire to see their political desires through to the end? Will citizens regrettably settle for a status quo that they are unhappy with but at least does not instill the fear of anarchy, pilots refusing to show up for duty, the grounding of the airport, and union strikes?

Moshe David Rubinstein

Moshe David Rubinstein I posed these questions to political activists from both my own camp on the right, and my friends on the left and it really did sum up the very ironic and idiotic reality which has led us here in the first place. For once we all agreed on one thing.

The high court will never allow a referendum.

Oh well, back to blocking roads then!

Moshe David Rubinstein is an Israeli and UK citizen, permanently residing in Central Israel having moved from Manchester, in 2009. A High-Tech Entrepreneur and advocate for Israeli startups, he frequently speaks on behalf of the Israeli innovation eco-system on the international business stage, inviting investors and businesses to explore innovative synergies.