A group of soldiers clad in wetsuits heads towards the pool for a training session, jogging past the amphitheater where the graduation ceremonies take place for Shayetet 13, the Israeli army's elite naval special forces unit.

Six of the most prominent Shayetet 13 commanders, returning to Atlit especially for this interview, give the young men a quick once over and chuckle to themselves: it's a different era to those of their service.

Related stories:

- Silent soldiers: Inside the IDF's elite naval commando unit

- Barak meets soldiers, praises operation against flotilla

- Maglan, Shayetet 13, Shayetet 3 win award for achievements

We assembled the six in an attempt to understand the magic behind the unit, which three months ago again made headlines with the takeover of Iranian arms ship Klos C. On a grassy hill in the heart of the base, the six reminisce about secret operations and daring missions behind enemy lines.

Despite the passage of time, or maybe because of it, for some of them returning to Atlit is akin to coming home. Eli Glickman, today the CEO of Israel Electric Corp., even parked his car in the space reserved for the unit's commander – as if his service hadn't ended a decade and a half ago.

Roll call: There is 88-year-old Izzy Rahav, who became the unit's commander in 1950; Reserve Major Gen. Zeev Almog, unit commander during the War of Attrition; Major Gen (res.) Yedidia "Didi" Yaari, now Rafael's CEO, who led the flotilla to remote destinations in the Mediterranean; Uzi Livnat, under whose his command thousands of immigrants were brought in secret from Ethiopian; Brig. Gen. Yishayahu "Shaikeh" Brosh, under whose command the unit assassinated Abu Jihad in Tunis and sunk a PLO ship in Cyprus; and as mentioned, there is Glickman, the youngest of the bunch, who as a commander had to deal with the trauma of the disastrous Shayetet raid on Hezbollah in 1997.

They spoke about almost everything, divulging details of daring operations and speaking out against what they see as excessive coverage to the case of the dives in the polluted Kishon river. They even criticized the controversial takeover of the Turkish ship Mavi Marmara. But when we raise operations such as the assassination of Syrian general Muhammad Suleiman in 2008, or the killing of head of Islamic Jihad Fathi Shiqaqi in Malta in 1995 – they smile and say nothing. There are some things that one just doesn't talk about, operations that will remain security secrets for many years to come.

Who had even heard of us?

Secrecy, they say, was a sacred principle in their time. Unlike today, when several of the unit's operations have been revealed in highly orchestrated PR stunts, serving, among other aims, political interests. Arms ships were seized in their time as well, the retired commanders noted – dozens of them far from Israel's shores. But what was then a secret known to few is today publicly lauded, even becoming the subject of Foreign Ministry posters.

"The Shayetet was a top secret unit for many years," Izzy Rahav explains. "There was no chatter. The press didn't write about it; its development was without almost any external outside contact. The IDF in fact contributed nothing, not even the navy. We are not familiar with this kind of openness.

"Until 1959, the Shaytet didn't even have its own insignia," adds Zeev Almog. "The unit was clandestine. We only got permission to wear the 'bat wings', the marine commando's insignia, in 1959. Two years prior to that, we began training with the French marine commandos, and information about our existence began to leak out. Until then, who even knew about us?

We didn't hear anything about the ships that were seized over the years.

"In the '70s, we stopped a ship attempting to smuggle arms to Lebanon," says Brosh. "In 1982, during the First Lebanon War, terrorists tried to send out many of their weapons, and we stopped their ships from here to Italy, including Yasser Arafat's personal vessel. There are times in which political interests and the naval interests converge, and you want to release some of the details of events."

"In my time we stopped 23 ships used by terrorists, and sunk seven," Almog says, "But I had objected to publicizing the information. I said that I didn't want reprisals from Algeria or Tunisia against ZIM ships, after which we'd have to send the Shayetet to rescue them."

When we talk about raids on ships, the Mavi Marmara incident becomes the main topic of discussion. Reports about the death of the tenth Turkish civilian who was aboard and the arrest warrants recently issued for former IDF chief of staff Gabi Ashkenazi and three other officers reignite a discussion on operational failures.

"The problem begins with the fact that you're going to raid a ship that has 600 people aboard," Brosh says. "When I was the commander of the Shayetet, the PLO planned the 'Al Awda' flotilla, sending Palestinian refugees to Israel – there were CNN crews, Japanese TV teams and what not. The ship was blown up in a harbor in Cyprus, and didn't even set sail. That's how things should be done."

The flotilla shouldn't have been stopped?

"Coming at the Mavi Marmara as they did – that's contrary to the concept of irregular warfare. That's not how the Shayetet operates," Brosh maintains. "There are other solutions that will do the job, from smoke grenades to other means that are better not disclosed."

In the beginning

"We started from scratch," relates Rahav, the second commander of the Shayetet. "We were three people: Yochai Ben-Nun, Moshe Nachshon and me. It was the time of the Second Aliyah, in 1946. The British captured Jewish immigrant ships and deported immigrants to Cyprus. We received an order to sink one of the deportation ships before the immigrants had boarded.

"We went to the Shemen oil factory and were given limpet mines stolen from British Navy warehouses. We took a boat at night to the British ship, which was anchored in Haifa bay. I swam to it and attached the mine – but nothing happened. The mine probably fell off or water entered the mechanism.

"The next day I swam out again. This time when we got to the ship I gripped the propeller to rest, and felt something dripping onto me. A British soldier had vomited on me – and he had seen us. The ship's alarm was immediately activated, and they started shooting into the water. We still managed to attach the bomb and take off. The following morning, we saw the ship tilted on its side. In terms of the morale of the Jewish people, it was a great success."

At the end of the War of Independence, the Shayetet's first commander, Yochai Ben-Nun, asked Rahav to find the unit a permanent base. "I traveled along the coast, and found this little bay at Atlit," Rahav says. "I was amazed when I saw it – it was perfect for our needs. We moved the base here, and as you can see, it still serves the Shayetet well."

At the age of 24, Rahav replaced Ben-Nun. The Shayetet was still a clandestine and compact unit.

"I finished my course with nine other fighters," Didi Yaari recalls.

"I finished mine with 13 fighters," Uzi Livnat chimes in. "The revolution took place during the War of Attrition. Since then the Shayetet has grown and learned to do things that surpass imagination. The old atmosphere remained, but today generals, Shin Bet and Mossad ask to use the unit's capabilities.

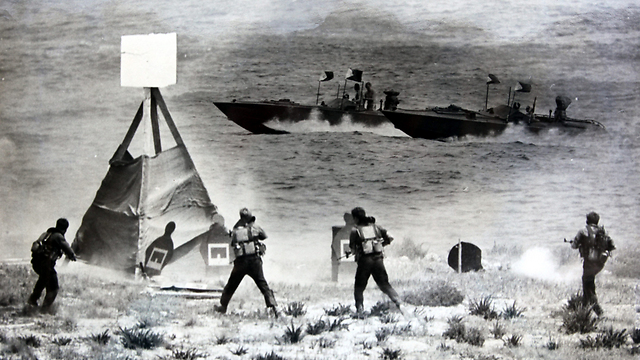

The Six-Day War was not the Shayetet's finest hour. Almog, who received command of the unit at the end of the war, terms it a "miserable failure". In his time, the Shayetet carried out a series of operations in the Gulf of Suez, including the Green Island raid on Egyptian radar posts and Operation Escort, which involved the sinking of two Egyptian torpedo boats in the northern bay.

Yaari was among the wounded in the Green Island battle, which involved both Shayetet and Sayeret Matkal troops. Commander Almog received an incorrect report that he had been killed, and quickly informed then-defense minister Moshe Dayan. Yaari comes from a prestigious family - he is the grandson of Meir Yaari, one of the leaders of the left-wing Mapam (United Worker's Party).

'No more infiltrations from the sea'

The lifting of secrecy restrictions on the unit can be linked to many of the changes in its operations. During the 1970s, the IDF failed to halt infiltrations by terrorists from the sea. There were attacks along Route 2 (the coastal road that runs from Tel Aviv to Haifa), at the Savoy hotel in Tel Aviv, and in the northern coastal town of Nahariya. And as the threat increased, the Shayetet became a unit that both initiated and attacked.

"As commander of the navy, I had a hard time convincing former chief of staff 'Raful' (Rafael Eitan) in 1979 to change the policy," Almog explains. "You don't wait for terrorists, you attack them. The Shayetet had already had vessels that could depart from Atlit and reach Tyre and Sidon (in Lebanon). We looked for locations from which we could strike at terrorists in their bases, and, together with missile boats and submarines, we began a series of operations in Lebanon, in effort to hit the terrorists in their bases. We created an unprecedented situation that not everyone is aware of - since the last terrorist attack in Nahariya 35 years ago, in which the family of Smadar Haran was murdered, there have been no more infiltrations from the sea."

During Livnat's days as commander, the Shayetet was in charge of Operation Moses, in which hundreds of Ethiopian Jews were smuggled into Israel.

"From 1981 to 1984, we conducted nine rounds of bringing Jews to Israel," Livnat recalls. "The Mossad picked them up and sailed them to the 'Bat Galim' naval ship, which was disguised as a merchant ship. In my day, the Shayetet sought to increase capabilities. There was one operation in which we sailed continuously for over 500 miles."

The unit continued to grow throughout the 1980s."The unit had entered a 'there's no limit to what you can do' mental state," Yaari says. "Shayetet 13, which is supposed to be a naval auxiliary unit, became a central unit. After all, delivered five navy commanders and an array of brigadier generals. The influence of this small unit on the navy and on the IDF is enormous.

"Much of the IDF's special nature – an army that initiates offensives, characterized by imagination and innovation – was born in the the special units, and the part played by Shayetet 13 is greater larger than meets the eye. The type of fighting that was born here influenced the entire IDF. You can find the Shayetet in Nablus and Jenin as well, because that's the war that's taking place, and you fight where you need to fight, even when the sea is not in the picture."

"In 1987, when the first intifada began, there were no commando units in the IDF," Brosh says. "The Operations Directorate asked that we operate in the territories. The demands on the Shayetet were so high, that I called the chief of staff and asked to set up units that could be brought in to replace it. That's how (elite) units such as Duvdevan, Shimshon and Egoz were founded, with the first commanders coming from the Shayetet."

Catastrophe

The Sayeret motto is "Like a bat out of the darkness, like a grenade exploding in thunder". But what was for years a source of pride came crashing down on the night of September 4, 1997. It is a night that Eli Glickman will never forget.

"For many years, the Shayetet did not suffer any casualties in its battles," he says. "Sadly, there were fighters who were killed in diving accidents, but not in operations. Half a year after I became commander, we conducted an operation in which we penetrated three kilometers from the coast of Lebanon. The force was comprised of 16 fighters carrying explosive devices. The operation left the Shayetet, for the first time in its history, with many dead and wounded."

What happened?

"Shortly before our arrival at the destination, I noticed three bombings deep inside the coast. It turned out that the Shayetet had ben delivered a fatal hit. Eleven fighters were killed, four were wounded and a Druze doctor from our rescue forces was also killed. What started out as an undercover operation evolved into a rescue operation, obviously a rescue under terrible conditions. In order to carry a stretcher, you need four fighters. When you plan an operation, you don't take into account every scenario in which someone from the forces is killed or wounded. Against all possible odds, an entire force unit had to be evacuated.

What did you do?

"These are moments that stay with me to this day. The first decision that I made, after a few seconds, was to dispatch rescue forces and helicopters. I acted on the basis of explosions because we had at that time lost contact with the forces. It was a very difficult decision. After a minute and a half, contact was made. The only one who wasn't wounded was the signal operator, and he explained to me not only exactly how severe the situation was, but that the force commander, (Lieutenant Colonel) Yossi Korkin, had been killed."

How did the disaster affect the unit?

"We changed at once. From a unit without a single casualty, we became a unit that was taking care of bereaved families. Not an easy task. First of all you have to test yourself: Did the unit fail because of you? If I'm to blame for the unit's failure, should I quit? How do you make the unit return to operational activities? How do you win back the trust of the chief of staff, and of the defense minister? I left the unit two years later. In those two years, we conducted many complex operations, more complicated even than those we did before."

Shaikeh Brosh is at a state of unease upon recalling the Shayetet catastrophe. During the incident, he was head of naval intelligence, and as part of his role, he had to prepare the intelligence background for the operation. In practice, the forces did not know that the terrorists had laid an ambush.

"I'm not ready to talk about it yet," Brosh says. "I have a much more detailed picture of what happened there, but the wound is still open, and not enough time has gone by."

'The bad taste remains'

Another difficult trauma that made headlines for the clandestine unit was the case of the River Kishon divers. For years, the Shayetet fighters had trained in the polluted waters of the Kishon, and only later was it established that there was a high rate of cancer among unit veterans. The findings led to a series of lawsuits that severely damaged the navy's reputation. "I took a blood test several days ago, and I'm clean," said a smiling Uzi Livnat. But more than anyone, Livnat knows that this is not a joking matter.

"I was the Shayetet commander when the story exploded," he says. "Suddenly I became the enemy of the bereaved families. It's as if I, who dove with the fighters, was responsible for what happened to some people. I think there were a few harsh exaggerations."

"Didi, who was then the navy commander, remembers how many tests we conducted to confirm that the dives didn't bring on the morbidity."

Yaari points out that, "there was a commission of inquiry. Its mandate was to determine whether there is a causal relationship between dives and the morbidity." Yaari says that the inquiry found no higher cancer rates among the divers than those who did not train in the Kishon.

"There were two professionals who were part of the commission of inquiry who came to the conclusion that there was no connection between the dives and the diseases," Brosh adds. "But Judge Meir Shamgar, who headed the committee, recommended that we act as if there were a causal relationship. We would be the last ones to stop our sick fighters from receiving treatment."

Yaari recalls moments of soul-searching in the wake of the commission findings.

"How was I to act as the commander of the navy? I dived in the Kishon quite a bit myself. We formed an assessment group - people who dived in the Kishon both as citizens and as members of the military. We put them through 18 different tests, and sent the results to lab in the US. Their answer was that there were no unusual findings. So what's left from that case? Mostly a bad taste in the mouth."

'We protected our very existence'

Do they have any second thoughts? Even today, long after they left their lives as commandos behind, they believe wholeheartedly in their way.

"Do I regret anything?" Yaari asks. "I have some doubts about whether I should have conducted certain operations in this or that way, but I have no doubts whatsoever regarding the essence itself."

"We protected our very existence as the State of Israel," Glickman says. "The question that stood before us was whether we conduct the operations, or have more attacks on Route 2. Our conduct towards the fighters was always open – the education the fighters undergo allows each of them to express themselves before heading out for an operation. Each fighter can say what's on his mind, even in the presence of the Shayetet commander, the commander of the navy and the chief of staff."

"Investigations and briefings were based on a democratic culture," stresses Almog. "But one shouldn't mix up the democratic atmosphere and the absolute belief in the righteousness of our way."

"We changed the terrorists' agenda," Brosh concludes. "Instead of terrorists spending 99 percent of their time planning and preparing their next steps for attacking us, we put them on the defensive in their own bases."