Israel’s most dangerous enemy: Who are you, Hajj Qasem Soleimani?

Following talks with intelligence officials, including former Mossad chief Tamir Pardo, Ronen Bergman and Iran expert Raz Zimmt profile the Quds Force commander and the Iranian Revolutionary Guards’ strongman in Syria—the one person capable of dragging the IDF to its next war with a single order.

Qasem Soleimani, commander of the Quds Force and the Iranian Revolutionary Guards’ strongman in Syria, was clearly seen standing and talking to Imad Mughniyeh, who was known as “Hezbollah’s chief of staff.”

According to different reports, this operation—which was one of the most sensitive operations led by the intelligence communities of Israel and the United States together—took several months.

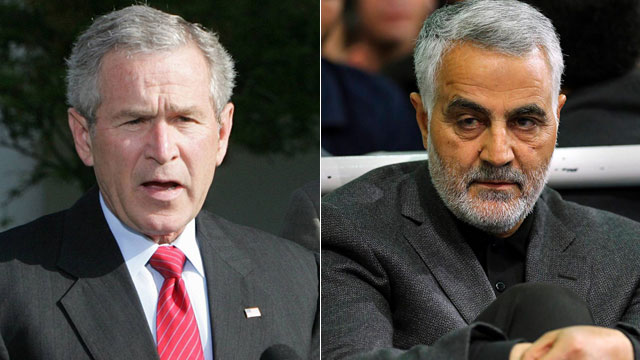

The Washington Post reported that in mid 2007, shortly after the Second Lebanon War, President George W. Bush gave the CIA his approval to launch a joint operation with the Mossad to locate and kill Imad Mughniyeh, the man who was responsible for the breakout and the results of that war more than any other person. The Americans participated because Mughniyeh was directly responsible for the death of hundreds of US citizens as well.

Hayden instructed his people to enlist all of the agency’s resources for the operation. Adam Goldman’s report in the Washington Post and Jeff Stein’s report in Newsweek outline different parts of the operation, claiming it was led by the Americans. Other sources provide an opposite equation, saying the Mossad needed the CIA’s help only in certain parts of the operation, mainly in tracking Mughniyeh down.

Either way, the operation was successful. Mughniyeh was located in Damascus and was placed for weeks under tight and highly complicated surveillance by the intelligence agencies across the Syrian capital, before the civil war era.

Until one morning, the time was right: Mughniyeh approached the car in which the bomb had been planted. The finger was on the activation button, but then it turned out that he wasn’t alone. He was seen leaning on a car, having a friendly chat with Qasem Soleimani.

The operation’s commanders wanted to seize the opportunity to kill two birds with one stone. Soleimani had been involved in numerous activities against Israel and had been responsible for the death of many Jews and Israelis. “Let’s take them down together,” the intelligence official said.

But that morning, the finger remained by the button without activating it. The reason was that the CIA is officially forbidden to carry out assassinations. It was only after the 9/11 attacks that the agency’s legal advisors generated a complex solution—a sort of euphemism—that while assassinations are forbidden, “targeted killings” are permitted in areas where the US is engaged in battle.

This trick allowed the CIA to launch an intensive assassination campaign against al-Qaeda in Afghanistan, Yemen and Iraq. Those days, however, the US had diplomatic relations with Syria, including an active embassy in Damascus until early 2012. In other words, Bashar Assad's country didn’t even come close to falling under the category of a “combat zone.”

For that reason, President Bush’s condition for the entire operation was complete certainty that Mughniyeh would be the only one to end his life. According to non-Israeli reports, the CIA and the Mossad conducted a series of experiments on the special bomb that was planted instead of the spare wheel of the Mitsubishi Pajero jeep, to ensure that only a person standing at a certain angle next to the vehicle would get killed. That morning, however, there were two people standing at that exact angle, and even hugging like old friends: Mughniyeh and Soleimani. Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, who was determined to keep his promise to Bush, ordered the Mossad to avoid taking any action. Soleimani survived. Mughniyeh was assassinated that same evening.

***

About four years later, a senior Israeli intelligence official met with a foreign colleague who knows Soleimani and even met him several times. The man described Soleimani as a brilliant person, a born leader with outstanding management skills and an ability to think outside the box. The foreign intelligence official further described him as an available and accessible commander, who is attentive to his people’s distress and shows up by their side at the heart of combat zones. The Israeli joked, “So can you get me a meeting with him?” The foreign intelligence official replied, smiling, that he didn’t think it would be possible in the near future.

The Israeli concluded from the conversation that Soleimani “isn’t someone who sits in his comfortable office, far away in Tehran, and mixes paperwork,” and that “he is a very, very dangerous man.” He was right.

A decade after that explosion in Damascus, it’s clear to everyone that if Olmert gave Bush his word—he had to keep his promise. There are, however, quite a few intelligence officials in both countries who very much regret the fact that Soleimani wasn’t taken down at the time together with Mughniyeh. The combination of operational abilities, personal charisma and courage have turned Soleimani into one of the greatest threats to Israel. And as Soleimani and Iran keep entrenching themselves near the Golan Heights, this threat just keeps growing.

Soleimani has another rare important skill: His survivability in the tough Iranian political system. About a year and a half ago, for instance, reports emerged in the media that he planned to run in the 2017 presidential election on behalf of the conservatives. It was unclear who had planted those reports: Soleimani himself, in a bid to pave his way to the top; or his rivals, as part of a plot to turn him into a new threat to the Iranian leadership.

In any event, Soleimani didn’t let this report stop him: He issued a rare statement, saying he planned to remain a “soldier” in the service of the supreme leader and the Iranian nation for the rest of his life. In other words, I am both politically strong and a loyal patriot. It seemed to work: A poll conducted recently by the University of Maryland together with an Iranian research institute revealed that Soleimani is the most popular personality in the Iranian public opinion, even more popular than Iranian President Hassan Rouhani.

He may have even gained too much power by now: According to unverified reports in the Arab media last week, there is a plan in Tehran to move him to a different position. While that may be true, it’s quite possible that Soleimani will be appointed to an even higher position. In any event, at the moment, Soleimani is Israel’s main enemy in Syria.

Mossad Director Yossi Cohen said in conversations with heads of European intelligence organizations, some of which were held during the latest Munich Conference, that Iran had managed to create a Shiite crescent “which may not be a Shiite crescent in the classic religious sense, but which will make it possible to transport a truck filled with missiles or other smart weapons from Tehran to the Lebanon coast. As far as they’re concerned, it’s a fulfillment of the Shiite Crescent vision.”

The man in charge of implementing this vision, according to Cohen, is Qasem Soleimani, “who reports directly to Khamenei (the supreme leader) rather than to Rouhani (the Iranian president), who Soleimani doesn’t feel subject to in any way.”

So who is the person who built the infrastrctures which, according to foreign reports, were bombed by the IAF in recent weeks—including the massive strike last Sunday, which reportedly destroyed some 200 missiles? Who is the general behind the Iranian deployment near the Golan Heights, the man responsible for sending a drone carrying explosives into Israeli airspace? Yedioth Ahronoth outlines the complex, sophisticated and multifaceted figure of Qasem Soleimani.

The living shahid

Over the years, the fog over Soleimani’s private life has been slightly cleared. Hajj Qasem Soleimani was born on March 11, 1957 in the village of Qanat-e Malek in the Kerman Province in southeast Iran, a mountainous area with a tribal population. He is one of five siblings. His brother, who is seven years his junior, is the director-general of the Tehran Province’s prisons.

Soleimani is married and has three sons and two daughters. One of his daughters, Narges, lives in Malaysia.

When he was 13 years old, Soleimani moved to the city of Kerman, the province’s capital, with a relative. He began working in the local water corporation to pay off his father’s debts. He was also active in sports, and according to some versions (likely those which he himself fosters), he has a black belt in karate.

Like many members of his generation, at the age of 18 Soleimani joined the battle for Ayatollah Khomeini. When the revolution succeeded and Khomeini returned to Tehran as a winner in 1979, Soleimani joined the Revolutionary Guards (known as the IRGC in the intelligence community)—the military force created by Khomeini to maintain his rule from the inside and export the revolution to other countries as well. Although he lacked any military experience, the talented 21-year-old stood out and began climbing up the organization’s ranks.

He embarked on his first command mission in late 1979, when he was sent to help crush a Kurdish separatists’ revolt in northwestern Iran. Soleimani was stationed in the city of Mahabad, most likely as part of an irregular force. He accomplished his mission, returned to Kerman and was put in charge of the local IRGC unit.

In the fall of 1980, when the Iran-Iraq War broke out, Soleimani was sent to the southern front. He apparently proved himself in the battlefield, as his next position was commander of the IRGC’s 41st Sarollah Division, which is considered an elite force. At the end of the war, the division returned to Kerman and was tasked with the battle against drug smugglers in the area.

Soleimani kept rising to the top, and apparently started making the right moves in the internal Iranian political game. In late 1997 or early 1998, he was appointed commander of the IRGC’s elite unit: The Quds Force.

“Quds is a highly confidential force. Its activities are completely disconnected from the official Iranian system, and it has built its cells across the world in a secret and covert manner, at least until the earth started moving in the Middle East,” says former Mossad Director Tamir Pardo, referring to the Arab Spring. “Its main goal is to export the revolution and encourage radical Islamic elements around the world.”

In the 1990s, most of Soleimani’s activity focused on one place: Afghanistan, Iran’s eastern neighbor. The Soviets’ departure from Afghanistan led to a growth in the power of the Taliban, a Sunni-jihadist movement which the Iranians (Shiites) saw as a significant challenge. Furthermore, the Taliban served as an incubator for the organization of another rising star in the world of global terror, one Osama bin Laden. It was another organization which the Iranians didn’t know what to make of.

Soleimani began specializing in a different type of an armed struggle, which is performed secretly and through proxies. He started operating mainly through the Northern Alliance, the Afghan opposition which was fighting against the Taliban. The Northern Alliance was also supported by the American CIA at the time. In this entanglement of two sworn enemies operating a wild guerilla organization against a third enemy, Soleimani proved that he is not only a statesman and a skilled operations man, but also a diplomat and a political tactician.

He understood, for example, that he would have trouble fighting bin Laden, so he gave him and his organization a certain freedom of movement through Iran. This freedom would later be exploited by some of bin Laden’s people in 2001 to launch the 9/11 attacks. It’s safe to assume that Soleimani didn’t shed too many tears that day.

Under Soleimani’s command, the Quds Force expanded and its missions increased. At the same time, his ties within the Iranian leadership grew stronger. One of his main sources of power is his close relationship with supreme leader Ali Khamenei. In 2005, in a meeting with families of fallen fighters from the Kerman Province, Khamenei addressed Soleimani with the rare title “a living shahid (martyr).” In early 2011, in an unusual move, the leader granted him the rank of major-general, which is identical to the IRGC commander’s rank.

“Iran is an organized country with bureaucracy and political struggles. It isn’t Hezbollah,” says Pardo. “In such a country, it is very rare to see a person remain in a considerable position of power for so long, gaining more and more strength rather than being pushed aside. Soleimani must be doing things very sensibly, succeeding in defining his authorities and power on the one hand, while making it clear to all other senior officials in the system that he is here—in the Quds Force—to stay, that he has no promotion ambitions and that he doesn’t pose a threat to any of them.”

The Quds Force’s main goal was and remains to “gain a foothold anywhere the revolution can be exported to,” as a senior Israeli intelligence official put it. That includes an all-out war against anyone who gets in the way of that revolution.

Like Israel, for example.

‘A golden opportunity’

Over the years, under Soleimani’s command, the Quds Force gained a lot of experience fighting Israel.

“My basic assumption,” says an Israeli intelligence official, “is that intelligence people anywhere in the world—in the Mossad, in the CIA, in the KGB or in the IRGC—are professionals who treat their job in a sensible, serious manner, free of any ideological incitement. I must say that when it comes to the Quds Force, this basic assumption has been significantly challenged. These guys, Soleimani’s subordinates, really hate us, Israel and the Jews. It’s a burning hatred. They despise us, and they come to work in the morning filled with motivation to use the day to plan how to inflict maximum damage and Jewish blood.”

The Quds Force waged most of its activity against Israel through Hezbollah. Some of the major blows Hezbollah dealt Israel in the Second Lebanon War had Soleimani’s name on them.

But Hezbollah is only part of the plan: Soleimani wishes to create much wider regional cooperation not only with religious and Shiite groups, but also with elements that have shared interests with Iran. The Military Intelligence Directorate’s Research Department refers to these elements to as “the radical front.”

The Iranians, for example, are cooperating with the Assad family members, who come from the Alawite community. Devout Shiites see the Alawites as heretics. But these religious issues have also been pushed aside by Soleimani, because Syria has something Iran doesn’t have and very much wants: A shared border with Israel.

Hezbollah and Assad are only two of the “radical front” members. The other two are Palestinian. The first one, which is relatively small in size and strength, is the Islamic Jihad organization, which Soleimani has been in close contact with for more than 20 years. The second one is much more significant to Israel: Hamas.

Hamas rejected Soleimani’s extended hand for years. The main reason was Sheikh Ahmed Yassin, Hamas’ spiritual leader and a devout Sunni, who didn’t want any Shiite hands in his battle with Israel. But as is often the case in the Middle East, this problem was solved by the joint enemy: Israel. When Sheikh Yassin was assassinated, the last obstacle in the way of a connection between Hamas and Soleimani was removed.

The assembly of the “radical front,” Israel’s most dangerous enemy today, was completed. With Iran’s backing, Hamas managed to gain control of Gaza and send a large part of country into bomb shelters during Operation Cast Lead and Operation Protective Edge; with Iran’s backing, Hezbollah launched an unprecedented missile attack during the Second Lebanon War; and with Iran’s backing, the Revolutionary Guards can see the Golan Heights’ farmers without binoculars. The proud father of all of this Qasem Soleimani.

Meanwhile, Soleimani was involved in more and more operations against Israel. Hezbollah’s Unit 1800, which was created with the Quds Force’s help and is used to encourage terror attacks inside Israel, conducted the Elhanan Tannenbaum abduction, for example. Hezbollah, in coordination with Soleimani, was responsible for the kidnapping of IDF soldiers Benny Avraham, Adi Avitan and Omar Souad in October 2000.

The kidnapping of IDF soldiers Ehud Goldwasser and Eldad Regev on July 12, 2006, which led to the Second Lebanon War, was planned by Imad Mughniyeh without informing Soleimani, who was furious about it. In retrospect, he was right: As a result of the fighting, Hezbollah’s abilities were exposed, Israel developed the Iron Dome system and other systems dealing with the threats Soleimani tried to create, and the attempts to settle the score with Mughniyeh were successful, according to foreign sources.

Mughniyeh’s assassination was followed by many other activities against Hezbollah: Mysterious bombings of arms depots south of the Litani River, attacks on weapons convoys, etc. These incidents undermined the organization’s internal stability.

The signs of pressure were particularly evident in the man who was appointed to replace Mughniyeh—his brother-in-law (who was also his cousin) and his deputy, Mustafa Badr al-Din. Al-Din started acting recklessly and sometimes wildly. He apparently started planning a series of aggressive operations against Israel and against Lebanese elements, without coordinating his plans with Soleimani or with Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah, and the two likely learned about it.

According to a report by the Al-Arabiya network, on May 12, 2006, Soleimani met al-Din at the Beirut airport for a difficult talk. Shortly after he left, al-Din’s body was found in the room. Israeli officials are convinced that Soleimani either shot him or ordered one of his men to do so. “That’s the way it is,” says a top military official. “Under Soleimani, there’s no retirement plan for senior Hezbollah members.”

But many senior commanders around Soleimani began losing their lives too: Islamic Jihad’s Mahmoud al-Majzoub in 2006; Izz El-Deen Sheikh Khalil of Hamas in 2004; his deputy and successor, Mahmoud al-Mabhouh, in 2010.

According to non-Israeli reports, the flames of this activity reached Soleimani’s doorstep. General Ali-Reza Asgari, one of Soleimani’s colleagues and a former commander of the Quds Force in Lebanon, went missing in February 2007. According to the non-Israeli reports, Asgari defected to the US, in an operation which Israel may have been part of, and shared everything he knew about Soleimani and his organization with the Americans.

Later, mysterious assassins operating in the heart of Tehran began killing Iranian nuclear scientists. While the Iranian nuclear program isn’t under the IRGC’s command, its security definitely is. Some Iranians argued that these failures were the result of mistakes made by the Revolutionary Guards, but Soleimani, who remained strong and highly connected, wasn’t affected.

And then something happened which no one—not even in Israel—had expected: The Arab Spring and its collapse, followed by the meteoric rise of the Islamic State (ISIS). Soleimani soon became a key player in worldwide political processes.

“Soleimani’s professional life can be divided into two periods,” says Pardo. “Up until the Arab Spring, he commanded a force which was perceived by most of the world’s countries as a terror group trying to create disorder wherever it could to promote a certain interest. He was very active in Syria, Lebanon and Turkey, but at the end of the day his main purpose was terrorism.

“But following the shock that hit the Middle East, and the emergence of ISIS later on, the man changes direction. He becomes a real player, skillfully using the secret infrastructure he has built for so many years to achieve overt goals: To fight, to win, to create a presence, to build a significant military infrastructure—for the purpose of producing international gains for Iran.”

When ISIS’s throat-slashing videos began spreading on social media, Iran and Soleimani suddenly seemed slightly less demonic. And when Soleimani started acting against the Islamic State, some people even claimed that he had joined the forces of light.

“The nuclear agreement provided Iran with rehabilitation,” says Pardo. “It was a golden opportunity as far as they were concerned: Both a popular war on ISIS and they suddenly turned into a state any other state, and Russia and China intensively resumed the economic relations with them immediately. Suddenly, there’s nothing wrong with being friends with the Iranians, because ISIS is achieving unusual success in the battlefield, and my enemies’ enemy is my friend.”

Vladimir’s partner

Soleimani’s war on ISIS also helped him tighten his relations with the new boss in the neighborhood: Vladimir Putin.

Putin didn’t care about Soleimani’s past or about the amount of blood on his hands, and Soleimani was invited to the Kremlin as an official guest. It was the first in a series of meetings, some secret, aimed at coordinating the operation to keep Assad in power.

According to a senior Israeli intelligence official, “Soleimani’s visit to Moscow in the summer of 2015 was what convinced the Russians to intervene in Syria, as the Syrian ground offensive began in October 2015. He was basically the one who convinced them that in order to save Assad, they must intervene.”

“Soleimani became the Russians’ partner,” says Pardo. “In this sense, he is very different from Imad Mughniyeh, who remained undercover and whose picture was never published. Soleimani has become a very public figure in recent years. This is happening only because the Quds Force’s activity is perceived as legitimate from a certain point.”

In the first stage of the war, the purpose of the Iranian involvement was to prevent Damascus and strategic strongholds in northern Syria from falling into the rebels’ hands—and essentially preventing the Assad regime’s collapse. In the next stage, which began around September 2015, the Iranians helped the Syrian regime expand its areas of control and stabilize its rule.

In the first stage, the Iranian involvement in Syria amounted to several hundred advisors and several thousand Shiite fighters from Hezbollah, who were joined by Iraqi Shiite militias and Afghan and Pakistani fighters recruited by the IRGC in return for a monthly pay and different financial benefits. The forces operated under the umbrella of the special “Syria corps” created by Soleimani. For the first time in the Quds Force’s history, it became in charge of thousands of other Iranian and Shiite fighters, who are not an organic part of the force. Soleimani is, in fact, commanding an army of his own.

When Iran moved to the next stage, it boosted its forces, likely with 1,500 to 2,000 fighters, some of whom took an active part in the fighting and reached impressive achievements.

Meanwhile, Soleimani became a sort of celebrity and kept documenting himself on the ground in real time, to ensure that the people in the Kremlin (and perhaps in Jerusalem too) know who is shedding blood for Assad. In June 2017, for example, he was documented near the Iraq-Syria border alongside fighters from the Fatemiyoun Division, which is comprised of Afghan fighters; in November 2017, he was documented on a visit to the Deir ez-Zor area—the place where Israel destroyed the Syrian nuclear project— which was liberated from ISIS. At the time of this visit, by the way, Soleimani was mourning the death his father, but he wanted to convey that duty comes before personal issues.

The months passed. The Syrians, together with the Russians the Iranians, started scoring more and more successes, until Assad's regime was completely out of danger. Now, Soleimani was able to move on to the real goal he had come there for: Entrenching an Iranian military force opposite the Israeli border.

The new Shiite crescent

Soleimani wasn’t the one who created the Iranian presence in Syria. Hezbollah already had bases in Syria for many years—depots for missiles and other sensitive weapons—but Soleimani was the one who realized that if Tehran made the right gamble on Assad in the civil war, Iran would be able to ask for anything it wanted in return—including a presence opposite the Golan Heights.

While fighting ISIS, Soleimani established a highly confidential Hezbollah unit under the command of Jihad Mughniyeh, Imad’s son. Samir Kuntar, the murderer of the Haran family who had become a symbol in Lebanon, was part of the unit too. One of the goals was to create terror against Israel.

According to non-Israeli reports, the establishment of this unit was closely monitored by the Israeli intelligence. In January 2015, the Military Intelligence Directorate’s sensors followed a convoy of vehicles patrolling along the Israeli border with Mughniyeh Jr. and the Iranian general training him. Air Force planes hit and killed the two of them.

This time, Soleimani made an exception and retaliated: Hezbollah fired antitank missiles at IDF vehicles on Mount Dov. Two IDF soldiers were killed in the incident and seven were wounded. Mughniyeh was replaced by Samir Kuntar, who was also killed later on in an alleged Israeli assassination.

In the past six months, as ISIS and the rebels have been losing, Soleimani and his friends have begun recalculating their route vis-à-vis Israel. This was also the background for the dramatic downing of an Israeli F-16 plane by a Syrian missile in February 2018. The previous time an Israeli plane was shot down was in the First Lebanon War.

The plane was launched after an Iranian drone infiltrated Israeli airspace, an incident Israeli rightly saw as a red line being crossed. It’s important to understand the context of this operation, however. In the months before the drone was launched, two activities attributed to Israel by foreign sources hit Soleimani where it hurts.

The first took place on September 7, 2017, when an Iranian and Hezbollah missile factory was targeted. The factory was in construction stages in Masyaf, within the protected compound of the Scientific Studies and Research Center (SSRC), a sort of Syrian Rafael.

The second operation took place about two months later: Someone launched an airstrike on a set of buildings that was going to be used as accommodation and training facilities for some of Soleimani’s Shiite militias.

These mysterious bombings likely led to a decision: This time we’ll retaliate and rephrase the rules of the game.

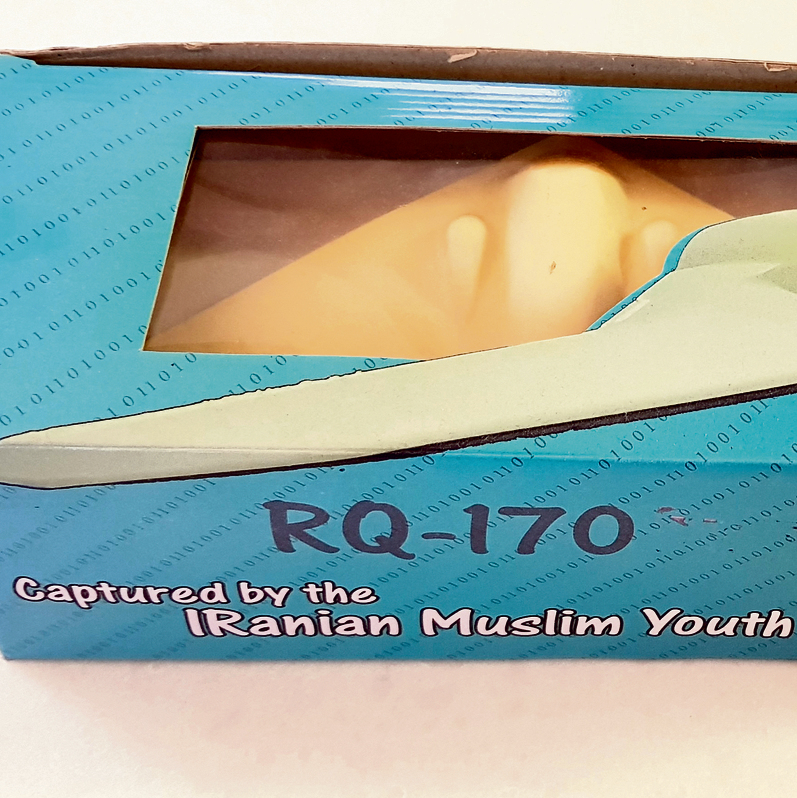

On February 10, on the night between Friday and Saturday, an Iranian drone was launched from a control center in the T-4 airbase. The drone was built based on an American stealth drone, which crashed in Iran in late 2011. The crash was marketed in Iran as a great victory, and the Revolutionary Guards’ souvenir stores in Tehran even sold a model of that drone.

The Iranian drone that was sent to Israel wasn’t an intelligence drone, but a drone carrying explosives. Defense establishment officials believe the plan was to detonate the drone in an open area or in a place of little importance, “only to signal to us, after the strikes attributed to Israel, that they have the ability to respond deep within Israeli territory,” says a senior security source.

After that dramatic night, Soleimani said that “Iran won’t settle for sending drones into Israel, but will work to wipe the Zionist entity off the map.”

It wasn’t a mere statement. Soleimani ordered a significant reinforcement of the Iranian aerial system in Syria, which is operated from a closed compound in the T-4 base, including a fleet of suicide drones, like the one destroyed over Israel. This system was damaged in the bombing attributed to the Israeli Air Force about three weeks ago.

Meanwhile, it’s quite likely that the name “Qasem Soleimani” was mentioned several times in recent months in meetings held between Mossad Director Yossi Cohen and his colleagues in the West.

“We have often heard in the past about a religious Iranian desire and an ideology to create a ‘Shiite crescent,’ an extensive area of influence under their values and activity,” Cohen told them. “How do you define a Shiite crescent? Well, in my opinion, as soon as Iran has the ability to send a truck with arms and advanced weapons from Tehran to Beirut, on a road, undisturbed, and if they want, all the way to Rosh Hanikra—it means Soleimani has succeeded in creating this Shiite crescent.”

The Mossad chief asserted that edging Iran out of the Middle East was his organization’s main goal. “Iran, which is located 1,500 kilometers from Israel, has succeed in creating an actual border with Israel, while Israel has no border with Iran,” Cohen told his colleagues. “First from Lebanon and now from Syria too, they can operate directly against Israeli communities and strategic targets in Israel. This is a very serious strategic threat faced by Israel.”

Dr. Ronen Bergman, a senior correspondent for military and intelligence affairs at Yedioth Ahronoth and a contributing writer for the New York Times, is the author of 'Rise and Kill First: The Secret History of Israel's Targeted Assassinations.'

Dr. Raz Zimmt is an expert on Iran at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS), at the Alliance Center for Iranian Studies at Tel Aviv University and at the Meir Amit Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center.