Cabinet meeting

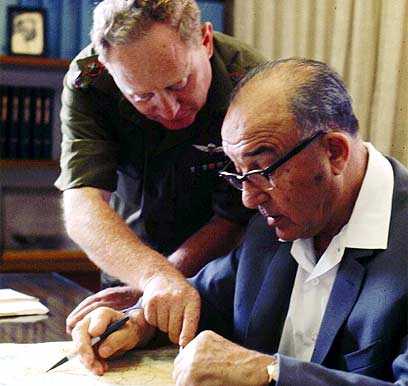

Major-General Ariel Sharon

Friday June 2nd 1967 was just an ordinary day prior to the outbreak of the Six Day War. Prime Minister Levi Eshkol, a wise man who the public had branded as indecisive, had so far withstood the pressure of the prolonged waiting period quite well. Initially, when he was informed of the large-scale Egyptian forces being deployed in the Sinai, he refused IDF chief-of-staff Yitzhak Rabin's request to call up the army's reserve units. He only agreed to raise the level of alertness for war. As one who was not eager to embark on war he took his time, yet it was at the cost of harsh public criticism.

In the meantime, he made every possible effort to prevent the war by diplomatic means. When that Friday came around, however, he knew that the time of decision had come.

Eshkol felt he'd been placed in a vice that was closing in on him from all sides. He was not a man of great decisions after all, and he never professed to be David Ben-Gurion.

Who could assure him that Egypt would not destroy the newly built nuclear plant in Dimona, as it had planned to? Who could assure him that half-a-million Arab soldiers, eager to erase the humiliation of the Sinai Campaign and the War of Independence, would not wipe out the young state that only recently marked its 19th anniversary? For himself and for the Israeli people, he was concerned about the consequences of a war against the entire Arab world.

He was being pressed from all directions. On the one hand there was US President Lyndon B Johnson, who didn't say anything unequivocal: Neither that he would open the Straits of Tiran, nor that he would press UN Secretary General U Thant to bring his forces back to the Sinai and demilitarize it again.

Waiting for America

Eshkol dispatched his eloquent Foreign Minister Abba Eban to Washington, who failed to secure an unequivocal assurance from the US that it would stand by Israel and work towards lifting the naval blockade. He also secretly dispatched Mossad chief Meir Amit. Johnson asked him to show moderation and also asked for more time. Eshkol had neither to give him.

The undecided Johnson only served as the anvil. Coming from other sides were the hammers that had been pounding at his head for the past three weeks; for example, the besieged economy. There was a shortage of oil and consumer goods, while factories and businesses were collapsing.

Coming from yet another direction were 35,000 men who had been called up for reserve duty, deployed in the sandy trenches of the Negev, Sinai and Gaza, and who had by then endured a third week of the nerve-racking waiting period and didn't know how much longer they would be able to hold out.

Then there were the cabinet ministers, headed by the Labor party's Yigal Allon, who were pleading to let the horses loose, and to let that defiant Gamal Abdel Nasser have it. Nasser had already dispatched six military divisions into the Sinai and closed the Straits of Tiran, blocking ships setting sail for Israel.

That Friday, three days prior to the war, Eshkol convened the security cabinet along with the IDF's General Staff at the Tel Aviv headquarters. The atmosphere was tense. Eighteen days had gone by since Rabin had informed Eshkol, who had been on the podium at the time watching the modest Independence Day parade in Jerusalem, that the first Egyptian forces had been deployed in the Sinai, marking the beginning of the nerve-racking waiting period.

Eshkol and Rabin with General Tal (Photo: GPO)

The security cabinet and General Staff meeting was held while Eshkol waited for the return of the head of the Mossad that night from Washington. The discussions lasted for two and a half hours, from 9 am to 11:30 am. Eshkol allowed his ministers and officers to air their views, while knowing full well that he would not declare war that morning before knowing whether America would stand by the side of its new friend in the event the USSR would get involved.

Ministers' reservations

The majority of ministers expressed strong reservations about going to war: They preferred to continue looking for a diplomatic solution, despite the heavy cost that a delay may entail. Heading this camp was Mapai's Zalman Aran and the National Religious Party's Haim-Moshe Shapira.

Even if an aerial assault would succeed, they argued, it would leave the north of the country exposed to Syrian attack. Moreover, Israel would embark on a war without firm American guarantees assuring its security. "I am ready to fight," announced Shapira, "but not to commit suicide."

Shapira asked probing questions during this dramatic cabinet meeting. He had become apprehensive in light of the digging of family ditches and mass burial graves that had started in Tel Aviv's Meir Park. "What protection do our cities have against bombardment?" he asked.

Menachem Begin, who had joined the cabinet a day earlier within the framework of the national unity government asked the chief of staff: If we launch an offensive in the south, and assume a defensive posture in the east, how risky would an armored corps assault in the north be? Zerach Warhaftig asked: Does our plan call for us to attack first? Namely, I don't want us to initiate the attack.

Major-General Motti Hod, the Air Force commander who three days later wiped out 400 enemy aircraft primarily on the ground within just a few hours in a plan codenamed "Moked," tried to pacify the ministers.

"To date, the best defense was the Air Force's power of deterrence. This is the case today as well. Our fear is that we are losing the Israeli Air Force's power of deterrence. Israel cannot defend itself against air strikes from within its own borders. To defend Israel we would have to attack the bombers or (to make them) realize that they are unable to reach us.

"The Air Force is ready for immediate action," Hod continued. "We can carry out the mission. There is no need to wait even 24 hours for us to take immediate action," he said assuredly, which still left Prime Minister Eshkol and his ministers hesitant and fearful.

And then came the outburst by several General Staff major-generals who were frustrated by the prolonged wait, but particularly because they thought the government did not trust them to deliver the goods.

Eshkol at his chambers (Photo: David Rubinger)

Generals' angry criticism

Major-General Moussa (Moshe) Peled demanded answers from the government: "The General Staff hasn't received a single explanation as to why we are waiting. I understand that we are waiting for something. If so, let the secret out and we'll know what we're waiting for! It (the Egyptian army) requires another year and a half for it to be prepared for war. In my opinion it is relying on the Israeli government's indecisiveness. It is doing so out of assuredness that we shall not dare strike at it.

"Nasser deployed ill-prepared troops to the border… one thing is working in his favor and that is that the Israeli government is not prepared to strike at it. Why does the IDF's capability deserve to be doubted… There is a lack of faith in our ability and in the questions asked here and on previous occasions. What does an army need more than winning every battle to earn the government's confidence?" he asked angrily.

Major-General Ariel Sharon, who even then sparked the ire of prime ministers, was adamant: "IDF forces are more prepared than they ever were to destroy and to ward off an Egyptian assault. Our goal is no less than to totally destroy the Egyptian forces, and because of hesitation and foot-dragging we have lost the primary deterrent we had, and that was the Arab nations' fear of us…

"We are destroying this with each day that goes by …since the War of Independence we have not faced such a severe situation. We have to go for it because we have no choice… going with the superpowers is nothing but a blatant mistake. Our objective…is that for a generation or two the Egyptians will not want to fight us…"

Peled could not be placated and had no qualms about leveling criticism at the prime minister, who he thought to be overly hesitant. "We asked for an explanation, what are we waiting for?"

Eshkol summed up: "The most important thing is the military front and the victory and the solution that would enable us to break the enemy's strength while remaining with a few friends in the world, who on the day after will assist us in rebuilding our strength.

"A military victory will not put an end to the matter, because the Arabs will remain here," said the prime minister, sending the ministers and General Staff away for another tense Shabbat before the dramatic cabinet session on Sunday June 4th, where it was decided, after a seven-hour session that Israel would embark on that war, 40 years ago.

And since that shining victory, and the capture of the Sinai desert, Gaza Strip, Judea and Samaria and the Golan Heights, the outcome has been dictating Israel's agenda.