Protests around the Arab world

Photo: AP

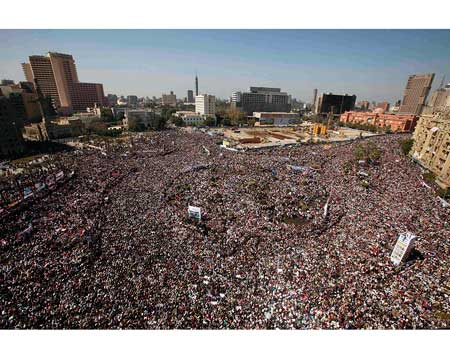

Calling for democracy in Egypt

Photo: Reuters

After weeks of nervous speculation, now we know exactly when and how the Mubarak era ended in Egypt.

The more important – and still unanswered – question is, what will the new Egyptian government (and possibly other regional regimes) look like?

Mideast Turmoil

Anav Silverman

Op-ed: As opposed to West’s hopes, Mideast anger premised on rejection of Western values

Dominating the headlines is the ostensible democratic dilemma whereby free and fair elections would bring an Islamist party to power. Contrary to the claims coming from tired (though evidently inexhaustible) post-modernist circles, the issue is not whether Arabs are seen as deserving of or inherently able to handle democracy, but rather, misgivings relating to the quality of nascent local democracies. This apprehensiveness is well-founded, given the history of weak Islamist commitment to democratic principles.

Examples of the latter abound, and relate to both how Islamists govern and for how long. The status of human and political rights under Islamist rule in Iran and Gaza, the indictment of Sudan’s president Omar al-Bashir on charges of war crimes and crimes against humanity in Darfur, and Hezbollah’s undisguised efforts to subvert the judicial process in Lebanon – after the party’s alleged involvement in political murder – all more than suggest that the fundamental protection of individual liberty that is the cornerstone of successful democracy ranks low on Islamist parties’ political agendas.

No less important is the question of the democratic, peaceful transfer of power. It is well understood that Islamist parties can succeed in gaining power through the ballot box. Less clear is whether these parties would be willing to relinquish political power at the end of their legally defined terms of office, if that were the will of the people. The concern, variously attributed to historian Bernard Lewis and to former US diplomat Edward Djeredjian, is that under Islamist rule, democracy would be limited to “one man, one vote, one time.”

Here too, the examples are discouraging. The memory of the corrupt 2009 Iranian elections is still fresh and the subsequent brutal suppression of dissent is ongoing. Just last month Hamas, lagging in the polls behind its Fatah rival, announced its refusal to participate in this year’s long overdue presidential and legislative elections announced by Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas, whose own term officially should have ended two years ago.

Arabs deserve better

None of this is to say that the Mubarak, Gaddafi, or other regimes in the region are necessarily more democratic than the Islamist governments that could replace them. Individual and political rights and regular, meaningful, free, and fair elections have long been in short supply. The use of force - reportedly including air power - against demonstrators in recent days and weeks shows how far some of the current regimes are willing to go to maintain their grip on power.

Replacing one kind of seemingly interminable non-democratic regime with another, however, will not address the demands of the publics, who deserve better. On the contrary, such a development could provide the fuel for a much larger political conflagration later.

It is too soon to say what the new Egyptian constitution and government will look like and how genuine and vigorous Egypt’s democratic institutions will be. For its part, the Muslim Brotherhood has announced that it will not field a presidential candidate in the upcoming elections, perhaps because it shares Hamas’ fear of electoral embarrassment and/or because it is always easier and often more popular to criticize from the opposition than it is to solve difficult political, social, and economic problems like those plaguing Egypt.

Less encouraging are the protesters' posters of Mubarak and Gaddafi with Stars of David on their foreheads and the recent announcement by the secular, liberal head of the Party of Tomorrow, Ayman Nour, himself a candidate for president, that “the Camp David agreement is over.” Nour reminds us that pointing the finger at Israel apparently remains an appealing populist tool in the hands of regional politicians, whether Islamist or not.

The author is a research fellow at the Institute for National Security Studies (INSS) at Tel Aviv University

- Follow Ynetnews on Facebook