'Why would anyone want to burn Jews?'

In spring of 1944, Martin Hecht and his family were sent to Auschwitz from village in Transylvania. 'People were dying like flies and we took comfort in the fact that there would be more room on the stools.' How did he survive and reach Israel? Third article in 'Remember Me' series

He pulled this random date out of his head in 1945, when he was asked for his personal details a moment before boarding a ship from Germany to Southampton, England, as part of a group of orphaned children who survived the Holocaust.

"Britain's condition was 1,000 orphans under the age of 16," he tells Ynet. "I was a little boy who survived the camps, I had no idea when I was born, so I made up a date. Thanks to the Romanian archives, I recently discovered my real date of birth."

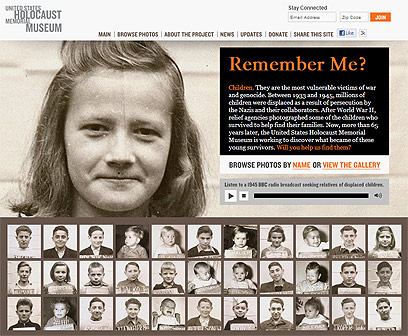

- For further information and the full list of displaced children, visit the "Remember Me?" website at http://rememberme.ushmm.org/

Hecht is finding out more and more details about his childhood and family thanks to extensive research conducted at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum as part of the "Remember Me" project, in an attempt to locate 1,100 orphaned children who survived the war and whose pictures were documented in different orphanages in Europe.

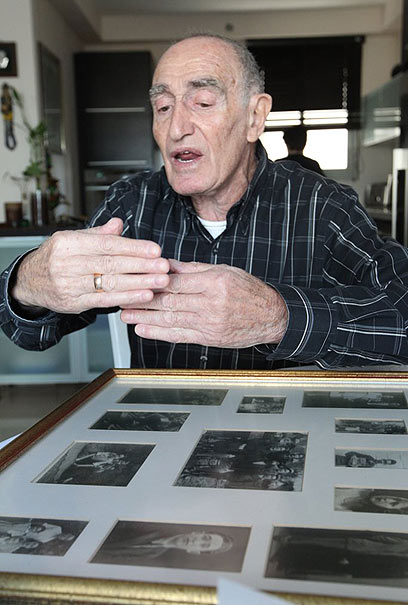

"The Germans were very organized," he says. "I was documented in every camp I was sent to during the Holocaust. The Holocaust Museum collected all that information and handed it to me."

'I was documented in every camp I was sent to.' Martin Hecht (Photo: Eli Elgarat)

Some of the material was collected by Anna Andlauer, who worked as a guide at the Dachau concentration camp site. She conducted extensive research on the orphanage at the Kloster Indersdorf monastery, where Hecht stayed at the end of the war.

Andlauer delivered her findings to the Holocaust Museum in Washington, and they became a significant part of the museum's project.

Moreover, Hecht adds, thanks to her he mustered the courage to visit Germany in 2005. Since then, he goes there every year to address students. Since then, he's willing to talk about what happened there – and about what was lost.

'What's SS?'

Hecht was born in the village of Ruskova in Transylvania into a well-established family which owned land in a village where most of the population was comprised of traditional Jews.

"The Jews were financially established compared to the non-Jews who worked our land," he says. "There was a main street with Jews' houses on both sides, and synagogues at the start and end of the street.

"We had good neighborly relations with the Christians, even though we sometimes encountered anti-Semitism," he recalls. "'Jew, go to Palestine,' the locals would sometimes shout at us – most of them of Ukrainian descent."

In 1935, the Hecht family considered immigrating to Palestine. The father of the family and four of his children, two sisters and two brothers, were granted a visa and looked into the possibility of settling in the city of Rehovot.

"My brother Moshe was the idealist. He encouraged the family to immigrate to Palestine," Hecht says. "Father decided to look into it and traveled to Israel for a visit. Two of my sisters and one brother stayed there, while my father and the youngest brother returned to the village in Romania and decided to further the visa process and immigrate with all of us."

But the war in Europe changed those plans.

While war raged in Europe and the mass murder of Jews was underway, life in the Romanian village continued, as if it were a different planet. Because of the geographical distance between the village and the city, and the fact that the village was technologically disconnected from the world, the village's Jews knew nothing of what was going on.

"There was no radio and no newspapers, and even no electricity in the village," he recalls. "The adults may have known something about the Jews' fate, but the children knew nothing. I didn't know a thing about the Germans. I had never seen Germans before."

Trying to locate 1,100 orphans (Photo: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum)

In 1940, the area became Hungarian territory. The Germans left their handling of Hungary's Jews for the end. Hecht remembers the day the Germans entered the village, in the spring of 1944, very well.

"Wehrmacht forces entered the village, dragging their artillery on horses because of the conditions in the area. We saw them coming from afar and got all excited. We didn't know who they were.

"The soldiers tied their horses in the big area we owned and we welcomed them in our home. We brought them food and made sure they were comfortable. We assumed they were hungry and tired. We knew nothing of their intentions."

The intentions became clear two weeks later, when SS soldiers arrived at the village alongside Hungarian police. It was a Friday, Hecht remembers, several hours before the start of Shabbat. The force set up barriers on both sides of the main street, and brutally entered the houses one by one, clearing the inhabitants who gathered outside the synagogue.

"'Raus!' The German soldiers shouted and removed the Jews out of their homes. No one understood what was going on and why they were doing it."

Hecht and his family were transferred along with the village residents to the nearby town of Viseu de Sus, where the Jews of the area were all expelled to and held in ghettos.

It was the first time he had left his village, the first time he was exposed to modern life and saw a light bulb with his own eyes. The shock, he says, was huge.

"Three weeks later, the SS soldiers ordered us to form lines again and led us to the railway station." The Hecht family boarded the second transport out of four. That was the moment when 12-year-old Martin realized that something bad was about to happen.

'Look at the chimney, boy'

"We were put on cattle cars and they began pushing people inside until there was no room to breathe. People were pushed against each other until some of them were crushed to death. It was shocking. You have to understand, it was the first time I ever traveled on a train.

"Several hours later, the train stopped and the doors opened. We stopped at the city of Sighet, where Elie Wiesel lived. There was hardly any room on the train, but the Germans kept pushing in more and more people.

"Today I understand that it was that stage in the war when they wanted to speed up the annihilation of Hungary's Jews, because they realized they were losing the war."

'Soldiers with raging dogs shouted, 'Raus!' Auschwitz (Photo: EPA)

The train traveled for two days, while more and more people died from suffocation, hunger or diseases. Suddenly the train stopped and the doors opened – it was the Auschwitz-Birkenau death camp.

"We saw armed soldiers with raging dogs shouting, 'Raus – out!' The people from the train were told to form two lines – men on one side and women and children on the other. My three brothers and I stood on the men's side, and my mother and sisters were sent to the other line.

"Suddenly, one of the soldiers pulled my father to the other line. The four brothers were left alone. We were led to the showers, our hair was trimmed and we underwent disinfection and were taken to the huts. It was the last time I ever saw my parents and sisters."

Hecht received a striped uniform and a number on his shirt, but unlike other Auschwitz survivors, the number was not tattooed on his hand. "The situation was so chaotic that they didn't give us tattoos. The transports from Hungary were so full and quick that they couldn't keep up," he says.

Hecht and his three brothers were taken to a hut, where they were greeted by the camp's veteran prisoners. "One of them, who saw the shock on my face, asked me: 'Do you know where you are?' I said no. 'You're in Auschwitz, there's no way back from here. Everyone dies here in the end.'

"I couldn't understand what he was talking about. 'Your family was already burned a long time ago,' he said. 'Look outside, do you see the chimney? This is where Jews are burned.' And I, a 12-year-old boy, didn't understand anything. Who's burning? Who's being burned? Why would they want to kill us?"

'We carried rocks, but didn't break down'

Several days later, Martin and his three brothers were put on a train again. This time it stopped at the Dörnhau forced labor camp. "A slaves' camp," he notes.

"We carried rocks, but didn't break down. City children wouldn't have survived, but we were strong in the village and knew what manual work was all about. I was a fighter," he says.

Under unbearable conditions, without food and in the terrible cold, they worked like slaves. "People were dying like flies, and we took comfort in the fact that there would be more rooms on the stools in the hut which were always crowded.

"One day, senior SS officers arrived and announced that the small children who could no longer work would be transferred to children's homes, and they ordered the kapos to collect 500 children for shipment.

"My brother Jack and I were told to stand with the group of children when suddenly, miraculously, one of the kapos who must have pitied me because I was the smallest one there, pulled Jack and me back to the hut and took two other children instead of us. The group was taken to the gas chambers and we were rescued."

The four brothers worked at the Dörnhau camp for about half a year. One morning, SS soldiers ordered the prisoners to form lines and begin marching. The Russians were already beating the Nazis, who began transferring the remaining Jews to other forced labor camps.

"It was a very difficult winter. We were wet and dirty, we marched for a month, and each time someone fell down he was shot to death. When we arrived at the forest the Nazis began a selection process. My two eldest brothers were separated from us and taken into the woods with another group. Jack and I were left all alone.

"Suddenly we heard gunshots. They were executed."

Martin later tried to locate the place where his two brothers were shot to death, but was unsuccessful. "There was a lot of chaos and this murder wasn't registered in the archives," he says.

Window overlooking crematorium

Martin and Jack were put on another train with the prisoners, when planes suddenly appeared in the sky. They were American jets, bombing the railroad.

"A friend of mine from the village was hit by shrapnel in the jaw. I was filled with blood but wasn't hurt. The SS removed us from the wagon and ordered us to march. One of them tried to separate Jack and me. We were so weak that we couldn't resist, but thanks to the havoc I managed to slip away from my group, grasp Jack's hand again and bring him to mine. The rest were executed."

They marched for days until they reached the Flossenbürg concentration camp in the Bavaria area, where political and Jewish prisoners were held.

"They sent us into showers with a strong flow of water, which was partly boiling and partly frozen. The flow and the temperature were so strong that some of the people died on the spot."

Martin and his brother were sent into a hut near the crematorium. "We were the closest hut to the electric barbed-wire fences and the execution area and road leading to the furnaces were in front of our window. We would see people being executed by gunshots or hanging and people being led to the crematorium.

"Nonetheless, I knew that I must stay alive. I was small but determined not to let them kill me," he says.

One day, as the US Army was approaching the camp area, the SS soldiers ordered everyone to form lines. The camps' gates opened and death march began. Those who fell down were shot immediately, while those who managed to stand on both feet hoped to survive at least one more day. Martin held Jack's hand and the two clung to each other so as not to fall.

The moment of liberation was sudden. "Before we could even say Jack Robinson, we suddenly saw American tanks and soldiers coming out of them and opening fire at the SS," Martin recalls. "One of the American soldiers, who was Jewish, shouted at us in Yiddish, 'Hide behind the tank.' They had already liberated several camps on the way and knew exactly who we were."

'The American soldiers didn't know what to do with us.' Hecht (Photo: Eli Elgarat)

And so, in one moment, Martin and Jack turned from Muselmann (prisoners suffering from a combination of starvation and exhaustion) into free men.

"The American soldiers didn't know what to do with us. They tried to help and even gave us chocolate and sweets, but that was the worst – people who survived the death march suffocated after swallowing the candy because they were so hungry."

Hours after the release, the soldiers moved on, leaving the survivors free but lost.

"Suddenly we were alone, free, and had no idea what to do," says Martin. "Where does one go from here? Where are we anyway? We saw a distant house and approached it. The landlord saw us, panicked and ran away. We entered the house, ate whatever we could fine and changed our clothes, but we mostly just slept."

Several days later, additional American soldiers arrived and took the survivors, including Martin and his siblings, to a nearby city, where a Jewish community which survived the Holocaust was being formed.

The children were taken to the hospital and released after medical exams. Then they were on their way again – this time to the Kloster Indersdorf monastery in the town of Dachau – where orphaned children who survived the horror were taken.

Thanks to the nuns' sensitive care, the children began adjusting to their new life, learned how to eat and sleep and mainly how to deal with the nightmares.

Turning point

Martin and Jack sought to reach Palestine, to be with their siblings who immigrated in 1935, but were banned entry to the Land of Israel. "They told us it was impossible, that we had only one option now – to go to England."

Martin and Jack were part of the group of children, some of whom arrived from the Theresienstadt concentration camp in the Czech Republic, who boarded a ship to Southampton.

England's Jewish community embraced the orphaned children. Martin and his brother were adopted by the community members and integrated into educational institutions. His dream to immigrate to Israel was shelved and Martin settled in England.

And yet, he found it difficult to rehabilitate his life. He remained lonely, and only in 1998 he married Aida and immigrated with her to Israel. They settled in Rehovot – the city where he was slated to live with his parents and siblings had the war not broken out.

For many years, he avoided talking about his experiences during the Holocaust. His wife, Aida, says that all her attempts to get him to talk were in vain. "He would close up and wouldn't share," she says.

The first visit to the monastery in Germany in 2005 was the turning point. "As a child, he lost his entire childhood," says Aida. "Martin has a phenomenal memory of history and small details, but he forgot everything from that period.

"But when he saw the archive findings – when he saw his name on the Nazi lists in the camps he was held in and the numbers given to him in each camp, the memories came back. He realized that he had a childhood, that he had a name and that he had a date of birth – December 10, 1931."

Yitzhak Benhorin in Washington contributed to this report