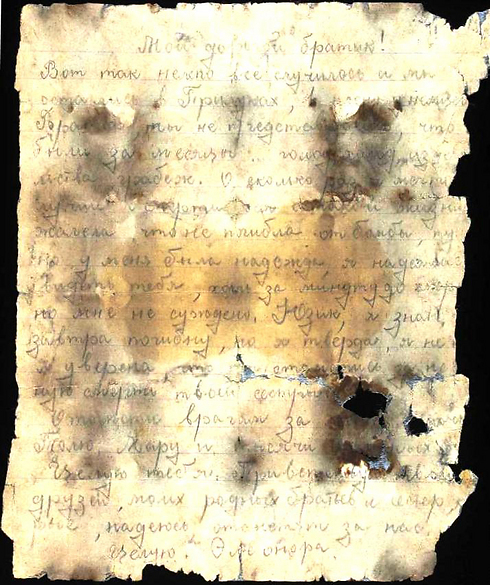

This farewell letter, which is now yellow and fading, is signed Eleonora Parmut, from the city of Priluki, Ukraine. She was 15 years old and was not expecting a miracle. It was clear to her that within hours of the ink drying on the paper, they would stand her in a line, would aim their rifles at her and her body would plunge into the killing pit.

And that is how it was. Around 6,000 Jews lived in Priluki at the end of the 1930s. Many of them fled in September 1941 when the city was seized by the Nazis. Some of those left were sent to the ghetto and others were sent to hard labor that many did not survive. In the end, the majority of the Jews remaining in the city – 1,300 men, women and children were murdered in two operations: In May and September 1942. They were lined up and shot into the killing pits. Some of them were buried alive.

But who was this Eleonora Parmut who left us this chilling letter? And what was the fate of her brother Yuzik?

Brutal and quick operation

“We will never know” says Dr. Lea Prais of the International Institute for Holocaust Research, who is attending a conference in Kharkov dedicated to the collection, research and mapping of the murder sites of the Jews from the former Soviet Union. “In Poland, Germany and France we found diaries that people wrote in hiding but from the Holocaust in the Soviet Union we found only one diary.”

The absence of such diaries is not accidental. “The Holocaust in the former Soviet Union was very brief,” she explains. “The country was occupied within several months – the operation was brutal and quick and the Jews were exterminated before they had an opportunity to develop a communal life under occupation.

"The Soviet Jews were also afraid of writing diaries. This was a result of years of the Stalinist regime where any personal writings put them in danger. They didn’t know who was going to find the diary. For the same reason they also spoke little and sparingly even during conversations with family members. Instead of diaries they left behind letters. A letter is a small thing that does not require a lot of time or thought, and I see them as a more democratic way of expression. They are the voice of everyone.”

Eleonora’s letter from Priluki was found by Dr. Prais in the Yad Vashem Archives. “Her family members lived in Azerbaijan and kept this letter and her picture like a lucky charm. When they came to visit friends in Israel, they gave the letter and the picture to a woman named Leah Basentin who in turn gave them to Yad Vashem. But she didn’t have any additional information and also didn’t know how to locate the visitors from Azerbaijan.

"In the last few years we have tried to make contact with Basentin, without any luck. Let’s hope that as a result of this article someone will turn to us. Perhaps we will be successful and find a clue that will lead us to the relatives of this girl."

“The Holocaust is the most researched topic in the world,” says Yad Vashem Chairman Avner Shalev. "In our library we have 140 thousand titles and the research will never be completed since the deeper we delve, the more we find that there was unique behavior in each place. The general pattern and the basic approach were quite similar – they gathered the Jews together and then murdered them – but for us it is important to learn how they coped. We are speaking about enormous amounts of material – diaries, and letters that will require many more years of work.”

Around one and a half million Jews were murdered in the territories of the former Soviet Union “mainly in ravines – the most famous of which is Babi Yar,” says Shalev. “The Nazis led the Jewish village to large killing pits to where they threw the slain – sometimes 10,000 people. These places have never been documented and this is the task before us now. We have identified more than 2,000 death pits and we are researching each site: who fired, in what language the order was given and the level of satisfaction reflected in the reports detailing the completed mission.”

The written eyewitness accounts speak for themselves. A report from July 16, 1941 which is categorized “Confidential Matter of the Reich” states: "In the first hours after the Bolsheviks’ retreat the local Ukrainian population undertook some praiseworthy actions against the Jews. For example, the synagogue in Dovreimil was torched. In Sambur, 50 Jews were beaten to death by an angry crowd. The Security Police rounded up 7,000 Jews and shot them as revenge for their horrific and inhuman actions."

A soldier called Franz proudly wrote to his parents: “Until now we have sent around a thousand Jews to the next world" and SS officer August Hepner wrote from the town Belaya Tserchov, Ukraine: “The Wehrmacht soldiers have already dug a ditch that will serve as a grave. The children were brought by tractor. They were lined up on the edge of the ditch and shot to death so that they fell within. It’s impossible to describe the howling. Some children had to be shot four or five times until they stopped.”

The research at Yad Vashem has led to the conclusion that the Holocaust in the Former Soviet Union must receive special consideration.

“During the Soviet period the Holocaust was presented as an integral part of the World War in which the Nazis murdered Soviet citizens – some of whom were Jews,” explains Shalev. “The Holocaust was not mentioned in the government educational system and harsh sanctions were applied to any researcher that dared to study this area. Some lone survivors, those whose entire families were murdered in the killing pits while they were fighting at the front, later came to the killing pits, collected eyewitness accounts and passed them on by word of mouth. Nevertheless, the authorities accused them of being traitors.”

Masha Yonin, born in St. Petersburg and now working at Yad Vashem, grew up in the shadow of this ambiguity.

“After high school I went to study in Estonia because in the city where I was born, Jews were not accepted to study the humanities” she relates. “I studied literature and Russian language and then returned to St. Petersburg, and together with my husband we joined the new Jewish movement that was set up by refuseniks. The Holocaust ripped up our roots, and we met in the refusenik underground, in private homes, to study Hebrew. Under the Stalinist regime Jews changed their surnames, were afraid to go to the synagogue, Jewish culture was wiped out, and cases of assimilation were widespread. The proof of this is in the fact that by the time the gates were closed, most of the Jews who wanted to leave the Soviet Union did not request to go to Israel but to United States.”

Unsurprisingly, the KGB did not relate positively towards the Jewish Hebrew studies in private homes.

“They used to come and turn the house upside down searching for Israeli newspapers, and if they found them they accused the house owner of undermining the state. When they confiscated the papers, they planted drugs among the bookshelves in order to accuse all present of dealing in drugs which carried a more severe punishment than nationalism. They wanted to ensure that we would receive long prison sentences, as in the case of Minister Edelstein who sat in prison, and they also wanted to humiliate the movement. They often used to say: “Who are the members of this movement? They are both nationalists and drug dealers.”

Despite the fear of being sent to prison, the movement’s members continued to meet in the Jewish underground “and alongside learning Hebrew we studied Torah, Jewish history and also about the Holocaust that was never mentioned in the Soviet Union,” Yonin relates.

“The Soviet ideology was that all are equal, that all the Soviet people suffered during the Great Patriotic War which is what they called World War II, and that the Jews were murdered like other Soviet citizens. If there was material in the library or the archive about the Holocaust it was in a closed, secret section which required a special pass from the director of that place, who in turn had to get approval from the KGB. Ninety-nine percent of the Holocaust survivors left in the USSR did not speak about what happened to them. Grandfathers were afraid to tell their grandchildren – for fear that tomorrow the grandchild would say something in school and then all the family would be in trouble and go to prison.”

In 1990, with the opening of the gates, Yonin and her extended family immigrated to Israel. She was 33 at the time and married. “A miracle happened to me,” says Yonin, getting emotional. “A friend of mine met with Dr. Krakowsky, director of the archives at Yad Vashem, who was searching for a professional archivist. My Hebrew was not good then, but within a month after making aliyah, I began working.”

The connection between the Yad Vashem and the government archive in Moscow was established a year before the gates were opened and the establishment of diplomatic relations between Israel and USSR. According to Shalev, only after the fall of the Iron Curtain did the void become apparent.

“They were eager for knowledge about the Holocaust. In the last two years, thanks to support from the Genesis Philanthropy Group and the European Jewish Fund, a quiet revolution has begun in the research and teaching of the Holocaust of Soviet Jewry.”

These activities include: Increasing dramatically the collection of materials from archives in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, the Baltic states and other places; uploading a new and comprehensive website in Russian which incorporates educational materials, virtual tours and online exhibitions; launching a YouTube channel in Russian; increasing the number of academic publications in Russian; displaying various travelling exhibitions in Moscow; publishing stories of the Righteous Among The Nations who functioned in these regions on Yad Vashem’s Russian language website; educational curricula for teachers and for youth movements and more.

“We started to photocopy materials from the Special Commission on Nazi War Crimes which had collected reports on what happened to Jews in each and every place. The library directors had no idea what materials were being housed in their archives because they were not permitted to see them,” relates Yonin.

She was the first from Yad Vashem to go to Belarus, and discovered the personal questionnaires of more than 12,000 Jews in their archives. “It turns out that the Nazis required that each Jew fill out a form in order to renew his passport, including pictures and fingerprints. I opened one file and then another, and there was no end to these surprises. This was a period of discoveries. Even the archive director had no idea what treasures were hiding there.”

The Belarus visit was also a strong personal jolt for her. “My father came from there,” she explains. “I found something that was connected to his aunt who was murdered in the ghetto. Her Russian husband locked her in the house so that she would not be found, and one of the neighbors, who was a policeman, reported to the authorities that a Jewish woman was hiding in that house. In the archive I found his letter informing on her.

“We searched thoroughly – until we discovered the fate of each Jew – who died, who fled to the eastern parts of Russia and was able to survive and who went to fight on the front and returned or died there. And so we were able to connect the pieces of the puzzle which until now was full of holes.

"But the picture is far from complete. In the area of the former Soviet Union, between one and a half to two million Jews were killed and we have only 25,000 names and personal stories. We clearly understand that we will never succeed in finding everyone, because in the eastern parts of the Soviet Union entire families were murdered without anything being recorded.”

Don’t cry for us

Dr. Lea Prais, together with her colleague from the Genesis Philanthropy Group, found more than 200 letters in the archive. Many of them, like the letter of Eleonora, aged 15, express the desire for revenge.

“We don’t like to stress the part about revenge since generally we want to be perceived as cultured people," says Prais, “but it is impossible to deny the fact that in their final letters upon parting from this life, the Jews expressed anger, humiliation and a desire for revenge. Some of the letter writers did not know what awaited them, but in the project 'The Untold Stories – the Murder Sites of the Jews in the Occupied Territories of the Former Soviet Union,' we will present parting letters from those who perished. They knew that they were going to be murdered and they were totally helpless."

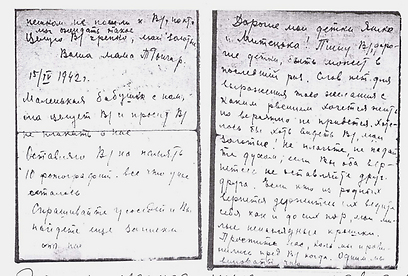

Each letter represents a mystery that is not always possible to unravel, like the one from Tomer and Aharon Guntser from Vinnitsa, Ukraine, to their two sons Yasha and Matya who were serving in the Red Army.

“I am writing to you both, my dear children, perhaps for the last time. There are no words that can express our passion to continue living but it is clear that this will not be. We would want at least to see you, my dear ones,” their mother writes to them. “Don’t cry. Don’t be sad. If both of you return from the front, don’t abandon each other. Forgive us if we ever hurt you. Our only sin is that we did not walk to where you are, but who could have imagined that this is what was going to happen?

"Your dear Grandma is with us. She sends you kisses and also asks that you don’t cry for us. I am leaving ten pictures to remind you of us. That is all that is left.”

And the father writes to his sons: “I am leaving you this letter, perhaps my last. Tomorrow we are going to the stadium; if they will leave us there, then I will write again. In meantime I will say goodbye to you. Be happy and healthy. Behave well and remember us and what we are going through. Continue to grow and be good. Look out for and protect each other. If you are still alive, it is a sign that you will continue to live. Yours, Father, Aharon Guntser, with love and kisses.”

The day after writing the letters, the Guntsers were taken to the stadium in Vinnitsa and from there by trucks to the killing pits where they were murdered.

“After much hard searching we discovered that one son died in a battle and did not get the parting letter from his parents, but the other brother survived and did get the letter,” recalls Prais. “We tried to find him, but it turned out that his wife is not Jewish and she didn’t want to hear anything about Yad Vashem, Israel or the Holocaust.”

The information about the family of Eleonora is also short on details, but Prais focuses on the photo of her where she is holding a book.

“Three years ago I was in Paris at an exhibition arranged by the municipality displaying photographs of Jewish children sent to the camps, particularly to Auschwitz, and all of them were memorialized while they are reading. I also have a picture like that, from first grade holding a book in my hand. To me, that is a typical Jewish pose.”