When he flew to Russia in order to marry me in a civil wedding he reminded me over and over that we would raise our children in Israel. "Okay, okay," I replied, "just let me learn to speak Hebrew so that I can make friends."

Shortly after my aliyah, I realized that one begins to make friends even before mastering the language – not because "Hebrew is a difficult language" but, rather, because people are quick to reach out in friendship. Blunt and direct – but full of warmth and love.

So it was. I made friends that spoke to me directly and allowed me to feel a sense of belonging, a feeling that only increased with the outbreak of the Second Lebanon War; and not only because I knew "brothers of" and "sons of" those called up north. For the first time I saw how a small nation became a large family. Most of you are used to this but I was stunned. It was then that I knew that I wanted to become a part of this nation and that I wanted to know more about Judaism.

With some basic Hebrew and a good deal of motivation I began to read all that I could on Judaism. The more I read, the more I felt that I knew this was my people. I understood the basis of Jewish family values, the nature of community, and the love for each person so deeply rooted in the tradition.

I adopted traditional practices and began to look into the meaning of conversion. I understood that it entailed a deep inner process that would produce deep spiritual changes in my life. I thought long and hard and in the end told my husband that I wanted to convert to Judaism. He - one secular person who had married another -was there to support me.

The first time I turned to the rabbinical court of the Chief Rabbinate, I was turned away. The rabbis told me I must first complete the process of becoming a citizen which I had begun with the Interior Ministry. This is a five-year process, so I had little time remaining. I used this time to learn even more about Judaism and to raise my daughter.

Once I had my Israeli ID in hand I again turned to the rabbinical court. They told me that if I earnestly wished to be Jewish then I must attend Torah study classes with my husband and attend meetings with the rabbis. I knew that I was prepared for some unpleasant times, but when I saw them demean my husband I began to think that perhaps I had made an error. The rabbinic judges saw him as a second-class Jew ("who told you that you are Jewish?" they asked him). From the moment he entered the courtroom, he was addressed with contempt; he was interrupted each time he tried to speak.

This was all very confusing for us. Twice a week we would attend three-hour evening classes. We would not see our daughter all day long and we would return home after she was asleep. The funds we had saved toward a home went toward paying a babysitter. Yet, the demeanor of the judges did not change.

Insult of rejection burned from within

Then came the final straw. The rabbis explained that if I really wanted to become a Jew, I must transfer my older daughter to an Orthodox kindergarten. I did not object. I loved the idea that she would grow up with Jewish values, but when I explained to her that next year she would have to switch to a different kindergarten rather than continue in school with her friends, she began to cry.

She was four years old and I could not find a way to console her. How could I explain that this was part of the conversion process? That in order to become Jewish I must cut her off from all of her friends.

I returned to the rabbinical court with a request: "One year. Give us just one more year with the current kindergarten." I explained that in just one more year when my daughter would begin a different kindergarten and that her friends would go off to different schools.

But the rabbis refused my request. "If you are not prepared to transfer your daughter to an Orthodox kindergarten, and to break off the connections with your secular friends, it is a sign that you do not really wish to become Jewish."

This did not feel at all right to me. I yearned to be Jewish, but both my daughter and I had many secular friends; good valuable friends who accepted me warmly when I first arrived here.

I explained to the rabbis that I started the conversion process to become a part of Klal Yisrael (the entirety of the Jewish people), and not part of a single denomination, but they did not relent. "Apparently this is not so important to you."

I was depressed for several months. Had Judaism cast me aside? I continued to observe Shabbat and the mitzvot that I had taken on, but the insult of rejection burned from within.

The solution to this conundrum actually came from an Orthodox friend who suggested that I turn to the Masorti/Conservative Movement. She explained that Masorti Judaism was committed to Halacha while also to "adjusting" to the needs of the times. "What, for example?" I asked. "Full equality between men and women, and I think they fast on Holocaust Memorial Day."

After an introductory lesson with a (female) Masorti rabbi, I immediately realized that Masorti Judaism spoke to me. I was pleased to know that my daughters could grow up within an egalitarian approach. Although I had not been involved in feminist struggles, when it came to my own daughters, it was important to me that they be raised with self reliance and not a sense of being held down by others.

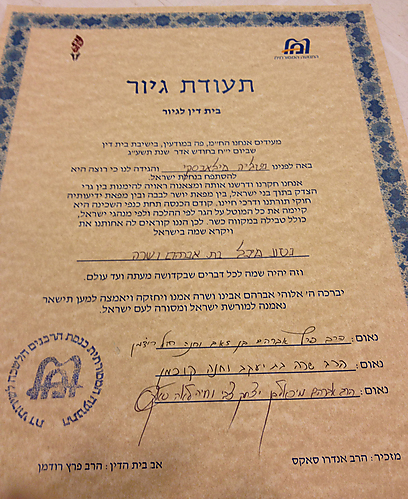

I continued to attend classes and completed the conversion process. It was deeply meaningful to me. I am happy I was able to convert with a sense of integrity, and not within a value-system I found disturbing. My daughter has since matured and her shyness has given way to tolerance. I am so pleased that I did not heed the rabbis.

It is important to me that people know that there is an alternative to the monopoly of the Rabbinate. Masorti congregants all over our country pray for the peace of Israel and send their sons and daughters to serve in the IDF. They have a passion for religion and a commitment to Zionism. They have created wonderful congregations. It is a shame that the state is demeaning by failing to recognize Masorti and Reform Judaism.

I am confident that this will change one day. I am convinced that the Chief Rabbinate will not succeed in destroying what I observed during the Second Lebanon War: One small nation that is, in reality, one large family.