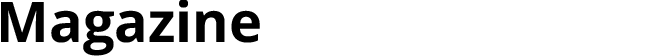

"This is an unusual day, a day like no other in terms of the hopes, in terms of the promise, and in terms of the determination, God willing and with God's blessing. Let us remember this day as long as we live and for future generations – Jordanians, Israelis, Arabs, Palestinians – all children of Abraham; we will remember and cherish this day, which is the dawning of a new era of peace."

- King Hussein at the signing of the peace deal, October 1994

Soon we'll be getting into the car that will take us from the Israeli border terminal on Allenby Bridge (King Hussein Bridge to the residents of the Hashemite Kingdom) to the Jordanian terminal – a drive of less than five minutes through two checkpoints, a long line of buses and a VIP service for those who can afford to indulge themselves. I passed through here for the first time exactly 20 years ago, with butterflies in my stomach – an emotional historic moment, three days before the signing of the peace agreement with Jordan. Back then, in October 1994, the director of the Israeli terminal, Gidi Shiklosh, ushered me outside, alone, and instructed me to simply make my way abroad on foot. "Just open the gate and step into the kingdom," he said.

At the time, I was wheeling a small suitcase and carrying a small bag into which I had placed a special present for Hussein – an album of rare photographs from the king's most private collection that were seized during the Six-Day War from the Jericho holiday home of the Jordanian royal photographer, Zohrab Markarian. One of the photographs is of a young Abdullah, Jordan's current king, carrying a suitcase on his way to an airplane; and in another of the photographs, Abdullah and his two sisters, the princesses, are playing in the palace garden. I crossed the rickety wooden bridge between the terminals with caution. Very few Israelis, only the peacemakers, made this journey back in those days, and only after "special coordination," behind the scenes were made with the palace in Amman.

Today, too, the bridge in the Dead Sea region that was built in the 19th century, bombed in the Six-Day War and then reconstructed with millions donated by the government of Japan is not intended for holders of Israeli passports. Thousands of Palestinians cross it every month, along with foreign diplomats and international aid workers. Foreign tourists and Israelis enter Jordan through the northern border terminal, in the Beit She'an Valley, or the southern gate, at the Arava terminal, where the peace agreement was signed. On that day, I recall, Allenby Bridge was abuzz ahead of the arrival of a VIP from the Jordanian side. I was asked in a firm tone to stand to one side and not dream of photographing Queen Dina, King Hussein's first wife who was on her way to the home of her second husband in the West Bank. Both have since passed away.

Related stories:

- Revealed: Peres' secret Jordan talks disguises

- Israel's most unsecured border?

- Opinion: Peace with Jordan invaluable

There's an air of expectancy at the terminal now too. Israel's ambassador to Jordan, Dani Nevo is about to arrive with his daughter, Nili, and two friends who are joining him for Shabbat duty in Amman; and waiting for him on the Jordanian side of the bridge is a convoy of bulletproof vehicles and armed security personnel. There've been shooting incidents here in the past, and no one is taking any chances. But 20 years of peace have made a mark nevertheless: The ambassador and his companions warmly embrace the Jordanian border officials; they exchange slaps on the back, greetings in Hebrew and Arabic and know the first names of one another's family members. The ambassador kisses whomever he needs to and gets into a bulletproof vehicle. Soon he'll emerge from it deep inside the fortress-like compound of the Israeli Embassy in Amman.

There's a wake-up call every morning at five: The Israelis at the embassy can't get used to the reverberating loudspeaker of the neighborhood muezzin at the Al Kaluti Mosque. An hour later, there's a second call to morning prayers, to rouse the lazy. The same mosque is the starting point every Thursday for demonstrations calling for the expulsion of the ambassador and the annulment of the peace agreement with Israel. The protestors scream and shout for 15 minutes and then go home. Last month, on the day of the final ceasefire in Gaza, some 300 Jordanian youths approached the security fence that surrounds the embassy compound; they had come to taunt the Israeli diplomats with chants of "Hamas was the big winner."

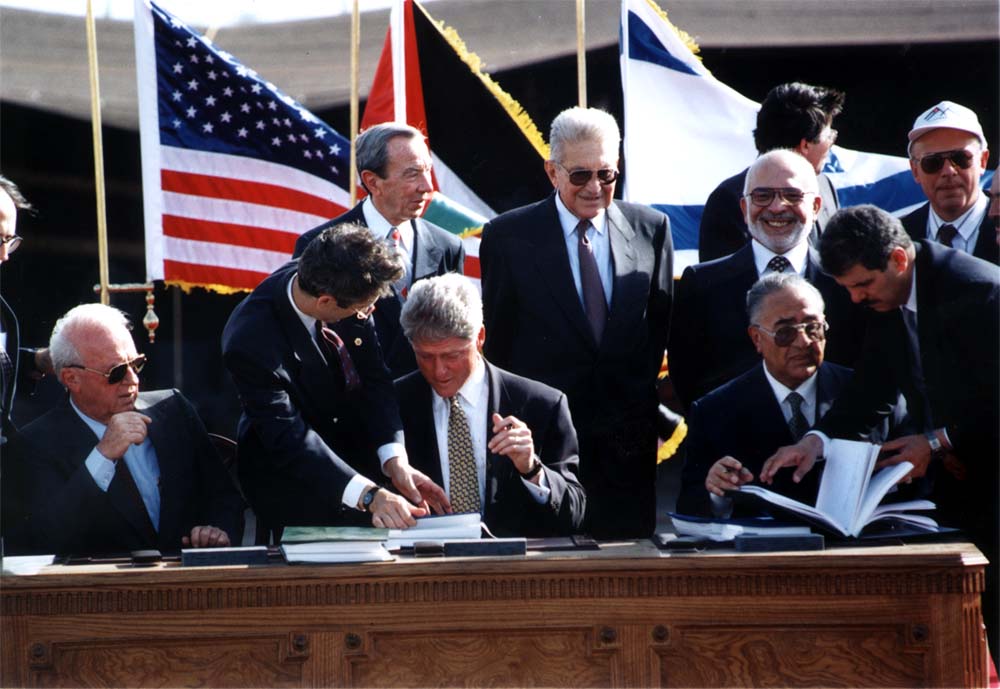

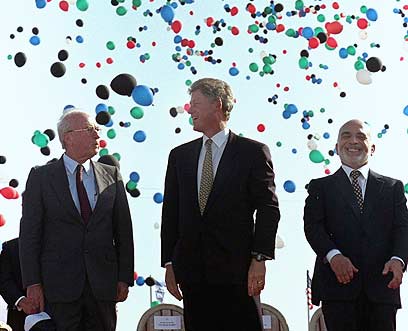

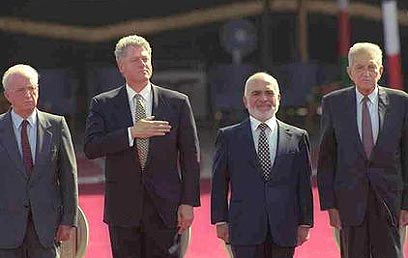

Back then, in October 1994, things looked different. Despite the bloody autumn that saw murderous terror attacks perpetrated inside Israel and the tragedy of Israel Defense Forces soldier Nachshon Wachsman's abduction, there was still room for optimism on the occasion of the signing of the peace treaty with Jordan. Israeli newspapers published features with lists of the kingdom's best restaurants, travel agents on both sides of the border welcomed the expected flow of visitors through the border crossings, Jordan undertook to do away with all anti-Israel propaganda, and Yitzhak Rabin and King Hussein exchanged warm words for one another and appeared to be truly fond of each other, and not merely for the cameras. More than 40 percent of the Israeli public stopped all they were doing that afternoon to sit down in front of their televisions to watch the hearty handshake and the balloons floating skywards.

In Jordan, too, there were high hopes for change, and an economic boost in particular – but the protest was already threatening to burst the bubble. And while the Jordanian government declared a national holiday, Jordanian security forces were deployed in the thousands throughout the country to prevent attacks on both Jordanian and US targets. In an effort to maintain order, a ban was imposed on anti-government protests; but members of unions of free professionals (lawyers, doctors and journalists, for example) hung black flags from the windows of their homes.

"This great valley in which we stand will become the valley of peace. And when we join together to make it bloom, as never before, we will build it and learn to live like we have never lived before. And we will do so, the Israelis and Jordanians, together, without the need for anyone to observe our actions or supervise our endeavors."

- King Hussein, October 1994

I met Dr. Dureid Mahasneh back then, while hopping back and forth between Eilat and Aqaba as the teams from both sides worked on the peace treaty. A mild-mannered and inquisitive man who was excited to meet Israelis, he spoke of the euphoria and high hopes and handed out his business card to anyone from our side who asked for one. Over the years, he has also visited Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. "The trust-building process has yet to be completed," he sighs as we speak now. "You didn't take the trouble to build up the peace between us in the political context, and not on the economic front too. Twenty years ago, we were all excited and built up huge hopes, and were sure we would see the fruits of the peace. But you promised and then disappeared.

"You haven't resolved the Palestinian problem; you've only made things more complicated with your construction in the settlements and the harm caused to the holy sites in Jerusalem. You spoke in length with us about plans for factories and economic projects, the free passage of goods, a free-trade zone, and what came of it all? Almost nothing. Who's to blame? As we see things, the blame falls on you, because Israel is strong and Jordan is the weak party. Over these past 20 years, we've come to the conclusion that you don't care about how we feel and what we need, and that the peace with Jordan isn't important to you at all," Mahasneh says.

Following the signing of the peace treaty, one Jordanian businessman, caught up in the excitement, opened a manufacturing plant in partnership with a businessman from Israel. They employed thousands of Jordanian workers and foremen and exported their goods to the United States. When we meet now at a private home, he asks to remain anonymous – "because I don't need to get into trouble with the opponents of the normalization," he says. The once large and successful plant, he tells me, has been significantly downsized, noting that his employees gave in to the pressure and stopped showing up to work, and that he remains practically alone in his support for peace. "The number of supporters in Jordan has dwindled to such an extent that they've stopped harassing us," he says. "In one instance, when the threats posed a danger to my life, the palace intervened and conveyed a warning to the intimidators.

"It wasn't a bed of roses on the Israeli side either," he continues. "One of my relatives was too naïve. He went and purchased two manufacturing plants in the south, and it turned out he was conned and that they sold him failing factories. When I look today at all that has happened in the years since the signing of the treaty, I come to the sad conclusion that both sides failed to build true peace between the peoples. There was an opportunity, and it was missed. I don't believe the opportunity will come around again."

Do you think we will get the chance to mark the 30th anniversary of the peace agreement, I ask him. "No one can say what will happen in a year's time even, let alone 10 years. Our region is filled with surprises and dangers. The agreement is a stable one, but the peace is not what you thought it would be and what we hoped it would be – and it probably will never be a true peace," the Jordanian businessman concludes.

"This is peace with dignity, this is peace with commitment. This is the gift that we give to our peoples and the generations to come and that will herald the change in the quality of life of our nations. It will not simply be a piece of paper ratified by those responsible, blessed by the world. It will be real"

- King Hussein, October 1994

So how does it feel to be an Israeli in Amman these days?

"I suggest you don't stay in one place for too long," advises a friend who comes to collect me to take me to her home. "Had I known you are Israeli, I would have thrown you out," says a cab driver, a Palestinian from Nablus who has family in Gaza, when I step out of his car. He guessed my origins when I got into the cab outside the Israeli Embassy compound and threw out a word in Hebrew; and when I responded, he wrapped himself in angry silence. Photographer Shaul Golan, who accompanied me on the trip, encountered a warmer welcome in the city's downtown market. His cab driver promised to look after him, and the stall owners offered him hot and cold beverages on condition he organized them work in Israel.

"I came to the conclusion that you don't understand the meaning of living with neighbors," says a confidante of King Abdullah during our conversation at a private home in Amman. "For me, the peace died twice – when Rabin was murdered and when King Hussein died. I knew that from then on, we were on a new path and that the extremists on both sides would get stronger. I fear today that no one here even thinks about peace any longer – just like the word peace has turned into a lowly concept on your side too."

Our tough conversation took place on condition I kept the man's name and particulars out of the newspaper. Like Dr. Mahasneh, he, too, was a member of the peace negotiations team. "I was young then," he says, "but I realized from the outset that despite the doves and colorful balloons that were released skyward at the signing ceremony, our relations wouldn't improve. The negotiations were tough; I caught on to the fact that Israel was only looking to gain from the agreement and that the bilateral ties between us were of no interest to you.

"You argued with us, for example, about how high the Jordanian airplanes would fly in the Israeli skies. Why is that important? You undertook to open a consulate in Aqaba to process Jordanian laborers who would work in Eilat; and in the end, you chose to employ Sudanese job seekers. There's still no joint airport for Aqaba and Eilat – despite the fact that it's included in the peace agreement – due to neglect on the Israeli side. Nothing has come of all the projects that Shimon Peres spoke about and promised. Danker, Tshuva and Stef Wertheimer spoke of 100 projects and presented plans to the king. Nothing transpired. Twenty years and tens of millions of dollars were wasted on feasibility studies. You didn't see Jordan as a true partner, and you didn't do anything to promote the ties by means of the economy."

When I ask him if he believes Israel to be solely at fault, he replies: "I don't absolve our side from all responsibility; but if you had gone for peace between the nations through economic means, and had upheld your promises and our expectations, the picture today would have looked very different."

"We have known many days of sorrow, you have known many days of grief - but bereavement unites us, as does bravery, and we honor those who sacrificed their lives. We both must draw on the springs of our great spiritual resources, to forgive the anguish we caused each other, to clear the minefields that divided us for so many years and to supplant them with fields of plenty."

- Yitzhak Rabin, October 1994

This summer, Israeli Ambassador Dani Nevo will come to the end of a particularly long stint of more than 11 years in Jordan – five as an attaché, and seven as the ambassador. He is in the know and well connected, and a well-known figure too. "However you look at it," he says to me in his home-fortress in Amman's Rabiya neighborhood, "the peace between us is truly unique. We share a long border. There exists cooperation that I won't discuss and am not completely familiar with, and don't want to know about either. There is also cooperation between the police forces when it comes to drug smuggling and human trafficking. There is economic cooperation and there are projects, even if they are being carried out under a different guise. Jordan is an Israeli interest, and vice versa – and this, too, does not sit well with certain people.

"Looking back, this peace agreement has survived a fair amount of problems and crises. We have a problem insofar as the public nature of the relations is concerned, and we find it difficult to leverage projects and encounters. Who's to blame? As I see it, the blame rests with both sides. We shouldn't have come on so strong and then disappointed. We should have started quietly, with small projects, and remained patient. But the Israeli businesspeople insisted on going for grandiose projects that weren't implemented. And on their side, the boycott against us by the professional trade unions definitely hampered things."

We end our trip just as we did 20 years ago, at the spic-and-span Zalatimo Sweets pastry shop – an absolute must for any Israeli who visits Amman. Behind the counter, Rabia, with transparent gloves on his hands, is weighing out "travel boxes," filling them with almond baklavas and pastries filled with dates and nuts. How are things in Jerusalem, he asks. He remembers me and asks about the mother-store in East Jerusalem.

Zalatimo, the father of the family dynasty who established the original shop, was born 150 years ago near the Old City of Jerusalem's Damascus Gate. All of the company's workers at its seven branches in Amman are Palestinians who fled or were expelled or declared missing, and managed to begin a new life in the kingdom. The Zalatimos make family visits, and the older ones, over the age of 35, receive entry permits into Israel. "I come and embrace the uncles and aunts, give out 'travel boxes' and take a walk around your Jerusalem, to see my childhood home," Rabia says. "I get a pang in my heart every time. I spot the Israelis who come to my store in Amman right away. I respect them and don't want political arguments. They aren't my friends. They're clients, like everyone else."

"As dawn broke this morning and a new day began, new life came into the world. Babies were born in Jerusalem. Babies were born in Amman. But this morning is different. To the mother of the Jordanian newborn – a blessed day to you. To the mother of the Israeli newborn – a blessed day to you. The peace that was born today gives us all the hope that the children born today will never know war between us – and their mothers will know no sorrow."

- Yitzhak Rabin, October 1994