The intensity of the tragedy hits them every day, everywhere, in every conversation and every meeting. There is no escape from it.

"A week ago I met a local social worker, aged 19, named Susan," says Yotam Politzer, an emissary in Sierra Leone for IsraAID, the Israeli international aid organization established by Shachar Zahavi that operates in dozens of disaster areas around the world.

"She said that she had just returned from a rural area infected with Ebola. She suddenly heard the sound of a child from one of the houses, approached and looked in through the window, where she saw a boy of about eight standing among a pile of corpses. 'Everyone died,' he told her. She had to give him instructions on how to leave the house without touching any of the bodies, while she called the evacuation and burial teams. Now the child is in isolation, and she hopes not yet infected; she cannot get the incident out of her head."

Politzer walks around with a thermometer in his bag. "I make sure to take my temperature three times a day. If I stop in the street and put it in my mouth, I look suspicious and people run away. So I take it in my hotel room and when I go to the bathroom. Until now, fortunately, my temperature has been normal."

Navonel "Voni" Glick, also from IsraAID, learned to adjust to a life that includes not touching anything.

"We explain to local residents that they must be careful and we also avoid touching people, the handrail on stairs or leaning on a pole on the street. I constantly keep my hands in check. If I'm out and I suddenly have an itchy eye, I can't rub it. There are protocols with instructions that you receive upon entry to Sierra Leone and they await you at the entrance to the hotel too."

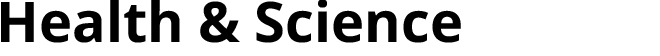

Dr. Yaron Wolman, head of Child Survival and Development for UNICEF in Sierra Leone, has not slept much in the last five months. Although he chose an unconventional career from the start, since the discovery of the first cases of Ebola in the small West African country, the young Israeli doctor has found himself, without any prior preparation, facing a medical and humanitarian war against the deadliest virus to threaten the entire world.

Every morning, just before the sun rises, Wolman stands in his office in the capital Freetown, ready for another day's work in the ongoing crisis, lasting until the wee hours. During the working day, it is standard for Wolman to face numerous difficult cases and tragic stories: babies who lost their mothers and need to find a replacement for breast milk; children found abandoned in empty houses; people who survived the epidemic but are unable to return to their homes and families because the community has banished them for fear that they are still contagious.

The three Israelis now found in the heart of the affected area are part of a broad multinational force mobilized to help prevent the spread of the disease. While many of their fellow volunteers are fleeing Africa for fear of infection - more than half of sufferers die in agony - Western countries such as Australia have closed their doors to travelers from West Africa and tourists are warned not to travel to affected countries for fear of infection, they chose to go out every morning into the heart of darkness, hoping they can help curb and even eradicate this terrible epidemic.

Soon they will receive reinforcements: Earlier this week, the Foreign Ministry announced that Israel will become involved in the international effort to fight the virus, and will send humanitarian aid to Sierra Leone, Liberia and Guinea.

The three countries will receive field hospitals, including tents, beds, coffins and stretchers, and medical and protective equipment for staff. Israeli assistance will also include the construction of treatment units on the ground; three paramedics have been recruited for this project.

"We are at war, and when I say war, it is not just a turn of phrase or expression," says Dr. Wolman. "We are at war with a terrible plague, which may become as much a part of medical mythology as Spanish flu or the Black Plague. We're headed for a disaster of biblical proportions. Everything you see in Hollywood movies about epidemics that wipe out the world is taking shape right before our eyes. Our war aims to prevent the eradication of entire communities.

"We have to set up new treatment centers and find qualified staff and equipment to protect them. These things cannot be dealt with by local governments. The world must understand what's going on and react quickly, otherwise the result will be unimaginable. It won't stop at Africa's borders."

Separated chairs

Earlier this week, the Health Ministry in Sierra Leone released worrying data, showing a dramatic rise in the number of new cases of Ebola in the country. Last Saturday, 45 new patients, half of them in the capital Freetown, were diagnosed. The day after, another 111 additional patients were found - the highest number since August."The reasons for the rapid spread of the epidemic in Sierra Leone are complex," says Wolman. "Infection occurs easily because of the religious beliefs of local residents when it comes to funerals and burials, which include a great deal of physical contact with the bodies. These rituals are deeply rooted in local culture. Added to that, there is deep public distrust of the central government. Because of this, it took several months to convince the local residents, especially in isolated areas, that to prevent the spread of the disease, they simply have to stop these funeral rites."

Given that the UN has warned that the number of officially reported cases is about half the actual number of infections, it is no wonder that Wolman is convinced that he is on a real battlefield.

"We are on the verge of a humanitarian catastrophe. The Ebola epidemic is a huge event, an emergency unparalleled in modern times. Everything we are dealing with here is for the first time, and we actually have to build everything ourselves. Starting with methodology - what must be done and how things will be done - through to complex coordination between all the organizations who work here to the daily management of specific crises: A huge volume of new patients, abandoned orphans, a local team member who was infected and we had to turn the world upside down until a Western country agreed to take him in, and communities that do not follow the necessary precautions."

The 44-year-old Wolman, originally from Jerusalem, has been in Sierra Leone for two and a half years. After graduating from medical school in Israel and starting a pediatric residency at Wolfson Medical Center in Holon, he decided to abandon the usual path and build a career in health systems management for international organizations abroad. And so he ended up with UNICEF, an organization providing aid in disaster-struck and war-torn areas, which is active in countries such as Syria, Iraq and South Sudan - and now West Africa. Wolman's first job was in Chad.

The next stop was Sierra Leone. His life is divided into two periods: before the deadly virus outbreak and after.

"The challenge before the Ebola outbreak involved a lot of very long-term planning. After years of bitter civil war, which ended 12 years ago and caused extremely extensive destruction, there was the need for rehabilitation, including the local health care system, the establishment of proper infrastructure and the training of doctors and nurses. We worked very closely with the local health department to help rebuild from the ruins. We did a good job, and we've already started to see real achievement."

But all that changed in May 2014. "The first case of a patient infected with Ebola was diagnosed in Sierra Leone on May 29," Wolman recalls. "Since then, we have been dealing almost exclusively in combating the disease, which threatens the existence of the entire country."

The first cases began in remote areas of the country, near the border with Guinea, where the first patient in the current global outbreak was discovered. The epidemic quickly spread among the three most affected countries - Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone - partly due to the relatively well-developed road infrastructure, which exacerbated the movement of the infected population, and because the local government and medical systems were not developed enough to deal with such a complex challenge.

"Once the virus reached the capital cities, containing the infection and isolation to prevent the spread of disease became almost impossible," says Wolman.

The trickle of patients became a flood that now threatens the very existence of the entire country. According to the local health department, approximately 2,000 new patients are discovered in Sierra Leone every month. By the most conservative estimates, these numbers increase exponentially every four weeks. "We are afraid to think what numbers we may reach in the weeks and months ahead, if we cannot halt the disease."

In an attempt to locate the new patients as soon as possible, and therefore try to reduce the fatality rate, Sierra Leone has implemented a system of hospitalization for patients who are suspected of having the infection.

"Any system of health care, even those for who have not yet been diagnosed and are only suspected of having the virus, must be integral. Anyone with symptoms that could indicate the illness, such as fever, weakness, headache or diarrhea, are immediately isolated and sent to a special medical center, while awaiting the test results. Even in the center, patients are separated to prevent further infection. If the results are negative, they are released immediately. If they are positive, they are transferred to centers which only treat Ebola patients."

This is all well and good in theory. In practice, Sierra Leone's medical infrastructure does not have enough hospital beds, and the majority of patients are forced to stay in their homes, where they come into contact with relatives who have not yet been infected, simply because there is nowhere to send them.

"We are currently trying to set up special community centers where it will be possible to place and hold people suspected of having the disease and keep them away from their family until the test results arrive."

You aren't afraid of being infected yourself?

"For us, the foreign aid workers, life here is very different from the conditions endured by the local population. It is easier for us to look after ourselves. The system of protection from the infection is very simple: No touching. At any professional or social event, people do not touch one another. There is no hugging or handshaking, and we keep a distance between our chairs.

"We are very careful to convey this message to the teams who work with us. For us, with our Western culture, it is easier than it is for the locals, but sometimes it's not easy for us either. It takes time to internalize, but eventually it becomes habit."

Is your family in Israel pressing you to flee?

"Most of the pressure came at the start of the epidemic, while it was unclear how the disease infected people. In recent weeks, the anxiety levels have dropped a little. I think they appreciate and respect my choice. I myself do not have any doubts or hesitation. It is clear to me that I am in the right place. All my training in medicine and medical management was designed to deal with precisely these situations. There is no greater professional challenge or satisfaction."

Changing the fabric of society

Voni Glick, 28, does not have any doubts either. Glick, a project manager for IsraAID, returned from Iraq just two weeks ago. In Iraq he was distributing medicines and equipment for winter to Kurdish refugees who had fled from the Islamic State terror organization. Two days later he landed in Freetown.

"My role is to study the picture of the area, do a survey of needs, map the international players and make contact with the local government," says Glick. "Our organization's expertise lies in assisting during the post-traumatic phase. This is a very large population of people who have experienced severe trauma, who have lost family members - sometimes their entire family - alongside people who managed to survive this ordeal and cannot return to their homes in the villages because of the severe stigma that makes them outcasts in society."

"Patients who have recovered and sent home live under a dark cloud," agrees Wolman. "Some are rejected by their families and by members of their community for fear that they are still contagious. Others have to deal with feelings of guilt that they infected people close to them and who did not survive the virus. We have established a large aid network to try to help these people reintegrate into the family and the community."

Glick this week attended a dramatic meeting, as he defined it, with people who survived the epidemic. "They told us how difficult it is for them to return to ordinary life. They get some form of authorization from the hospital of 'okay, now I'm not sick with Ebola', but the population is reluctant to believe them. A patient recovering from Ebola may transmit the disease through sex for three months, and it very difficult to explain this complex situation of 'yes, I'm healthy, but I still can infect.' This results in people surviving but facing new tragedies. A husband will not allow his recovering wife to go home, a wife locks the door on her recovering husband."

Although the epidemic has already spread to the capital of Sierra Leone, the city continues to operate as normal, at least outwardly. "Life must go on," says Wolman. "People get up and go to work or go shopping in the market, simply because they have no choice. They still laugh and tell jokes. People here are very warm and friendly. This is Africa. But the city may look normal only to those who did not know it before, because beneath the surface there is a great deal of stress and anxiety."

"In front of every public building - hotels, government offices and neighborhood supermarkets - there are faucets with chlorine and washing your hands is compulsory," says Glick. "A security guard stands at the entrance to give you a disposable thermometer, which you must use in his presence. If your temperature is over 38 degrees, he immediately calls an ambulance to take you into isolation."

"Schools and kindergartens effectively closed in June," adds Wolman, "and right now it seems the children will lose an entire year. Current conduct runs contrary to the warm African culture, where there is significant support from the family, community and neighborhood. Today it is impossible to continue the relationship in such a manner. The disease has not only changed daily life, but the entire fabric of society here.

"There are many orphaned children. If the parents have died from the disease, then there is a greater chance that the children carry it. We need to find a way to take care of these children without endangering others with infection. Now people are refraining from visiting the clinics to even treat simple diseases such as malaria. A lot of women prefer to give birth at home so as not to be infected by Ebola.

"Even many members of the medical teams and caregivers won't go to hospitals and clinics for fear of infection. In the special centers to treat Ebola, the staff is well protected, but the main danger is at the regular clinics, where there has been a mass abandonment by local workers who simply fear for their lives and the lives of their families. Some of our efforts are devoted to trying to explain to them about infection and prevention."

The tsunami was easier

Yotam Politzer, 31, from Mitzpe Harashim in the Galilee, returned to Sierra Leone this week. He went for the first time in September as the projects coordinator for IsraAID in post-trauma treatment - after a trip to Tokyo to meet up with his Japanese wife.

"I've been in many disaster areas in my life," says Politzer. "In Haiti after the earthquake and later the tsunami in Japan. Usually we arrive in the country after the disaster has occurred, not in the throes of it. To arrive in a third world country while a deadly epidemic is raging is very scary.

"The main reason that dozens of people in Sierra Leone continue to be infected every day is the harsh living conditions and poverty. They live in shacks, 10 people to a room, and if one of them is infected, everyone is infected. The situation would be much worse if we abandoned the Africans. When certain countries prohibit refugees from Sierra Leone from entering, they do not realize it is a mistake. They will find a way to enter, and then the danger is far greater, for the entire world. We have to help, not shy away."

"The only way to stop the epidemic is to get up and help," agrees Wolman, "but it is easier to mobilize assistance for victims of a tsunami than a country hit by the epidemic. It's not easy to find qualified people who will help combat the virus. We need to find people with a teamwork mentality, who are ready to run a marathon, not a sprint, and are not in it for a reward. It is also very difficult to find sufficient quantities of protective equipment. The global industry, which is used to producing several thousand protective suits per year, is now required to immediately provide millions of units. It is difficult to find equipment of sufficient quality and get it out here."

Save for treating patients and removing dead bodies, the bulk of the work of the medical staff is devoted to explaining infection prevention methods. "There is a huge public relations campaign about how you should act during this period and what to do if there is suspected infection," says Wolman. "The situation today in the capital city is better than it was a few months ago, but it is not easy to change patterns of behavior. It's a process that takes time. Today there is an increase in the number of patients who come on their own initiative to be tested, but a large number of patients still refrain from seeking help."

Unlike the situation in the capital, ignorance still prevails in the villages, says Glick. "People understand that the infection is achieved through body fluids, but because you only start to experience the symptoms after 21 days, you may not know if your neighbor is a threat. When someone starts to get a temperature, the villagers refuse to send him to the hospital or for isolation. They ask, 'If you say there is no cure for Ebola, what's the point in getting him out of the house?' Others say, 'Anyone going to hospital never comes back, so maybe the problem is in the hospitals who don't know how to treat the disease?'

"In the villages you find a lifestyle that really invites infection, such as how they handle the bodies. Among the hospital staff, doctors and nurses and technicians are dressed in protective suits, but the people who purify the bodies for burial are working with their bare hands. We contacted the religious organizations, Muslim and Christian, and we even recruited the community radio stations to explain that in light of the gravity of the situation, it is now permitted to bury the dead in a different way. Do not wash the corpse of an Ebola patient or lower it into the ground with your own hands, but wrap it in a sealed bag, pour in large amounts of chlorine and bury it in the ground as soon as possible."

"The epidemic presents great challenges for the medical emergency teams, but also the opportunity to have an influence," says Wolman. "The major bottleneck is people. We need skilled medical and logistics staff, who can set up the treatment centers needed here. Israel has an excellent reputation for the deployment of field hospitals during an emergency. Hospitals of this kind, with all their equipment, would really help here. "

"During a workshop for the medical teams that was held last week, the nurses said that they are afraid to get up and go to work in the morning," says Politzer. "For several months already they have been treating patients, most of whom they know, and they are in need of support on a regular basis. We are copying the models of workshops for cancer patients and for bereaved parents that were developed in Israel. Working with the body through drama and music very much connects to their culture and we are building a new model for exercises to release anxiety - touch without touch. Africans are very warm, hugging and touching, and now they cannot even shake hands."

"We meet people in very difficult situations," says Glick, "and we want to hug them to express sympathy and give support. But the rule is 'no hands'. We are not allowed to hug or shake hands – it is very hard to treat someone without touching them. "

Weekly beer

Ostracism is not unique to the local population. Aid teams are also often met with aloofness and suspicion by those who hear where they work. Wolman says that employees of foreign aid teams, evacuated to their home countries for fear of infection, are shocked to learn that their family and friends do not welcome their return.

"We heard stories of colleagues who were told explicitly not to return home. On Friday, one of my colleagues cried as she told me that her family did not want her to visit."

But even in the ongoing state of emergency and despite fears of the spread of the epidemic, foreign aid teams find time to rest and relax.

"There is something surreal about our lifestyle," says Wolman. "On one hand we are in a humanitarian catastrophe, on the other hand this is not a war, and there's no shooting on the streets. Despite the chaos, there is still a sense of control.

"We need to find time to preserve our sanity. So at least once a week we go out in the evening, a group of strangers, to eat together in one of the few restaurants still open and drink a beer. To try to create a sense of normality, we have clear rules and regulations: on these evenings, we do not talk about Ebola."