The Israeli-Palestinian conflict in 2014

From failed peace talks, to Palestine recognitions across Europe, it has been a tough diplomatic year for Israel, and though the year ended with the successful attempt to block the Palestinians’ Security Council resolution, the conflict seems to be going from bad to worse.

The past year has been a turbulent one for Israeli diplomacy, particularly when it came to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and the Foreign Ministry did not always rise to the challenge with poise and rationality. From failed peace talks to a damning summer war, with constant settlement construction looming overhead – this is how history books will remember 2014 in this corner of the Middle East.

Crash landing for peace talks

US Secretary of State John Kerry's peace effort started in July of 2013 in Washington with Kerry smiling from ear to ear behind the podium of the press room at the State Department, flanked by Israeli negotiator Tzipi Livni and Palestinian negotiator Saeb Erekat.

But the optimism that accompanied the launch of the talks quickly dissolved and shortly before the clock ran out on the April 29, 2014 self-imposed deadline, talks collapsed altogether, serving as the opening shot for a string of losses for Israel on world stage, and a year of fleeting, small victories for the Palestinians.

After Fatah and Hamas announced their reconciliation, and the formation of a Palestinian unity government, Israel, unwilling to negotiate with Hamas, a terror organization bent on Israel’s destruction, matched the Palestinian move with an announcement of its own – that it will not release the fourth and final group of security prisoners that were to go free as a part of a"goodwill gesture" to Palestinian President Abbas. Moreover, Israel threatened to slap the Palestinian Authority with a string economic sacntions.

Peace talks could not survive that mutual death blow, and they came to a screeching halt, with no hope to resume them in sight.

While Livni refused to give up, holding an unsanctioned meeting with Abbas in London in May, the talks were already given up for lost by both sides to the sound of worldwide condemnation and feeble, futile calls to return to the negotiating table.

Settlements ‘poison the atmosphere’

Publicly, American President Obama laid the blame on both sides. Behind closed doors, however, US officials told Yedioth Ahronoth that the Netanyahu government’s refusal to “move more than an inch” on settlement construction is what “poisoned the atmosphere and doomed any chance of a breakthrough with the Palestinians.”

Peace Now, a left-wing NGO, reported that during the nine months of peace talks, Israel has approved nearly 14,000 new homes to be built in the West Bank and East Jerusalem – territories the Palestinians want for a future state.

While a settlement freeze was not a pre-condition for talks as it was in 2010, Israel has, according to Peace Now, set a new record for settlement expansion, owed in part to the presence of national-religious party Bayit Yehudi in the government and the appointment of hardliner Uri Ariel as housing and construction minister.

Not even repeated world condemnation – from the United Nations, the European Union, the Arab world and repeatedly from Israel’s biggest ally the United States – could make the Israeli government slow its construction in disputed territory, a theme that remained prevalent throughout the year.

War and a failure of hasbara

The summer of 2014 saw the situation deteriorate further. A constant trickle of rockets fired from Gaza at southern Israel turned into a downpour that made it all the way to Jerusalem, Tel Aviv, and even Hebron. Even before rockets could reach that far, Israel decided it had had enough, and launched a military campaign against Hamas in Gaza.

Operation Protective Edge, which lasted 50 days, claimed the lives of 72 in Israel (six of them civilians and the rest IDF soldiers), and over 2,000 Palestinians (with disputed numbers of combatants and civilians), and saw big parts of the Gaza Strip reduced to rubble.

Despite having justifiable reasons to launch the campaign – putting a stop to unrelenting rocket fire at Israeli civilians and destroying Hamas' network of attack tunnels burrowed under the Israeli-Gaza border – Israel's diplomatic corps and the IDF hasbara machine were unsuccessful in convincing the world of the validity of these reasons.

The incessant torrent of videos, photos and graphics released by the IDF Spokesman in English and Arabic seemed no match to images coming from the Strip of complete and utter destruction. The IDF Spokesman's efforts were mostly featured in the English-language Israeli press, and largely ignored by the world press.

The Israeli Foreign Ministry and its missions abroad also made an effort at hasbara – Israeli Ambassador to the UN Ron Prosor unleashed scathing remarks against the Palestinians at the General Assembly, and even played the Code Red rocket alert siren in an attempt to help the international community understand the plight of Israeli citizens under constant rocket threat.

The UN responded to speeches by both Prosor and Palestinian envoy Riyad Mansour with repeated condemnations of both sides, and after the fighting ended, announced an inquiry commission, led by William Schabas, a Canadian human rights professor who has a history of damning comments against Israel. The Israeli government decided to choose that moment to demonstrate intransigence, announcing it would not cooperate with the inquiry commission – despite calls from Schabas himself, who reasoned Israeli cooperation will allow Jerusalem to tell its side of the story.

Fight for the Temple Mount

Ever since Israel captured Jerusalem’s Old City in the 1967 Six-Day War, with division commander Mordechai “Motta” Gur uttering those famous words "The Temple Mount is in our hands!" on the comms system, Israel has had control of the Temple Mount. But under its peace treaty with Jordan, control of the holy sites in Jerusalem – including the al-Aqsa mosque compound on the Temple Mount – was given to the Hashemite Kingdom.

So when Israel decided to repeatedly limit entrance to the Temple Mount to women and male worshipers over 60 with an Israeli ID, in an attempt to put a stop to the regular Friday clashes between Palestinians and Israeli security forces at the site, and eventually decided to close the compound to both Muslim worshipers and Jewish visitors after an attempt was made on the life of right-wing activist Yehuda Glick – an avid supporter of allowing Jewish prayer on the Temple Mount - it raised the wrath of the Palestinians and the Arab world.

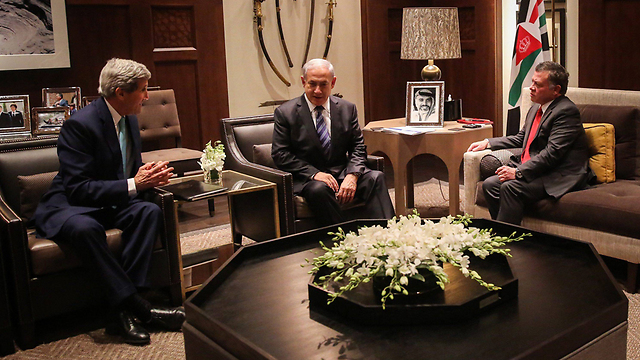

After a series of condemnations, threats and continuous Palestinian rioting, Prime Minister Netanyahu has agreed to open the Temple Mount after being called to an urgent meeting in Amman with US Secretary of State Kerry and Jordan’s King Abdullah II. And while some would view this as a smart diplomatic move on Netanyahu’s part, others, particularly inside Israel, saw it as capitulation to the Palestinians.

Recognizing Palestine

By the end of 2014, the collapse of the peace talks and the massive scope of death and destruction in Gaza following the summer war have led more and more European states to lend their support to a unilateral recognition of a Palestinian state.

Some European parliaments only managed to get as far as symbolic, non-binding resolutions urging their governments to recognize Palestine while others, most notably Sweden, officially recognized the Palestinian state, to Israel’s dismay.

While the Europeans were debating on whether or not to throw their support behind the Palestinians' diplomatic efforts, Israel decided to respond with punitive measures – the Foreign Ministry reprimanded Swedish Ambassador to Israel Carl Magnus Nesser, and recalled Israeli Ambassador to Stockholm Isaac Bachman to Jerusalem. Bachman has since returned to the Swedish capital, but the nasty exchange between Foreign Minister Lieberman with his Swedish counterpart about putting together IKEA furniture was not one of the minister’s finest moments of diplomacy.

The Palestinians have also been taking steps of their own to advance their agenda on the world stage. They submitted a resolution to the UN Security Council calling for a unilateral establishment of a Palestinian state in the pre-1967 borders with East Jerusalem as its capital, which sets a 2017 deadline for Israeli withdrawal from territories the Palestinians intend to include in their future state.

But the resolution came just one vote shy of the necessary 9-votes majority it needed to pass and was subsequently not adopted, due in part to intense effort by Israeli diplomats but owed by and large to immense pressure created by the United States to prevent the motion from passing.

The Palestinians have threatened to cut ties with Israel should the resolution fail, and made good on their threat to turn to the International Criminal Court (ICC) at The Hague against Israel. They were made observers at the ICC, a move they say gets them closer to achieving full membership. Such moves, however, will play against the Palestinians. Cutting ties with Israel can only damage the Palestinian economy – that still depends on Israel for water and electricity, among other things – and turning to the ICC can also open the door to war crime suits against the Palestinians.

Israel dodged a bullet on December 30 when the resolution failed to pass, but the 8 “yes” votes the Palestinians did get at the Security Council – including support from France, China and Russia – and the fact five of the 15 countries – including the UK - chose to abstain rather than vote “no,” will serve to embolden the Palestinians and encourage them to continue making unilateral moves on the international stage.

As the situation stands, a diplomatic resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is most likely not in the cards for 2015. A lot rides on the results of the Israeli elections in March, and on whether or not the Israeli right resumes power, this time unhindered by centrists like Yair Lapid’s Yesh Atid and Tzipi Livni’s Hatnua.

A lot also seems to ride on whether or not the Palestinian reconciliation government – a technocratic body which Hamas has since said failed at its job – decides to return to the negotiating table in earnest, and if Israel will be willing to hold talks with a Hamas-linked political body.

In light of all of this uncertainty, combined with the deeply-rooted mistrust made worse by years of fighting and failed negotiations, the Palestinians see no way out but to continue making unilateral diplomatic advances on the world stage, while Israel will most likely work to thwart any such advances.

At the same time, unless Israel chooses to freeze the highly controversial construction in the disputed territories, it will risk continued isolation while the Palestinians, ironically the David to Israel’s Goliath, will continue winning international support.