Housing prices soared and the office of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu did little to address the problem, State Comptroller Yosef Shapira states in a much-anticipated report published Wednesday.

Poor government planning and disregard for the middle class played key roles in creating the current severe housing crisis in Israel, which could have a devastating impact on the entire economy, he says. Shapira found a shortage of tens of thousands of apartments, while moves to combat the skyrocketing cost of renting and purchasing a home in Israel remained mostly on paper.

Related articles:

- Israel's housing crisis: Massive price increases across the country

- Housing Ministry plan: One fifth of new homes to go over Green Line

- Tensions rise in political arena ahead of housing report

- Tensions rise in political arena ahead of housing report

The 294-page indictment of government policy warns that the middle class could actually collapse, which would have a knock-on effect on the country's economy as a whole.

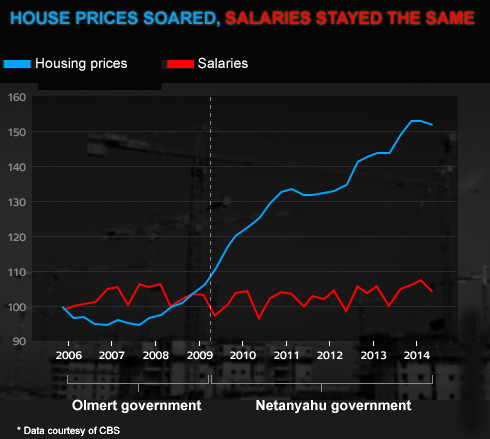

It paints a picture of long-term inefficiency leading to the sharp rise in housing prices that began in 2008, at the tail end of Ehud Olmert's term as prime minister, and continued all the way into 2014, Netanyahu's sixth consecutive year in office.

"The proportion of expenditure on rent for those in the middle deciles rose from 21% in 2008 to 26% in 2012 (an increase of 24% in housing prices), and this rate is approaching a threshold of 30%," the report states. "This raises concerns that if this trend of rising house prices continues, and the upward trend in wages is relatively more moderate, more sectors of the population will be exposed to financial risk that could impair their ability to meet these expenses."

From 2008 until December 2013, house prices have leapt by some 55% and rent prices have increased by 30%. Shapira writes that, "One reason is the lack of tens of thousands of apartments created by the limited scope of building starts in relation to the increase in the number of households."

Meanwhile, wages barely rose in that period, and Shapira writes that, "in the face of soaring housing prices, the average income for households only moderately increased."

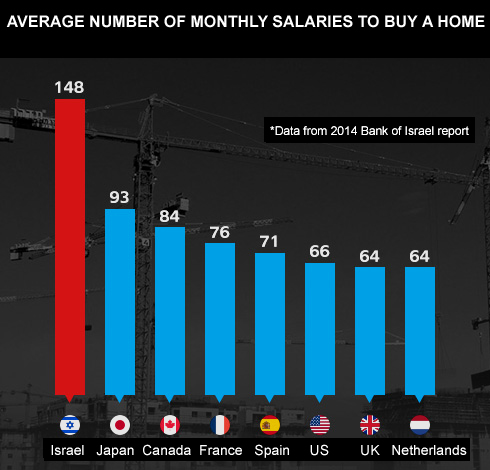

Shapiro highlights data from the Housing and Construction Ministry that shows that in 2008 (during the Olmert government), Israelis needed 103 monthly salaries to buy an apartment, while by the end of 2013 it had reached 137 salaries. It currently stands at 148 salaries, while the average in the US, UK and Netherlands is roughly 65.

The consequences, the state comptroller warns, could be deleterious for both the middle class and the disadvantaged.

"The burden of housing expenditure may have far-reaching implications for the life and well-being of the individual, and his economic robustness. If these trends continue, they could adversely affect the whole economy," he says.

Basic needs in danger

In examining housing prices, the comptroller went as far back as the 1967 Six-Day War. He found that from 1967, there were marked changes in Israeli house price index, which is also an indicator of significant volatility in the housing market. But, he notes, "from January 2008 to December 2013, there has been a real increase in house prices at a rate of 9% per annum. This growth rate is significantly higher than the rate of increase over the last 47 years."

Shapiro also focuses on those who cannot afford to buy an apartment, and therefore remain in rented accommodation. He warns that, "The increase in expenses is especially noticeable among the six lowest deciles - some 470,000 households. While this is 20% of the total households in Israel, it is about 73% of households who rent apartments."

The comptroller also also found that the proportion of net income spent on rent for the lowest three deciles (approximately 285,0000 households) stood at 30% or more.

The comptroller also warns that, "crossing this (30%) threshold points to possible harm to the ability of households to pay for basic living needs. It increases their financial risk and could lead to real harm in their standard of living". Furthermore, the proportion of the average monthly salary spent on rent rose from 29% in January 2008 (the Olmert government) to 38% in December 2013 (the Netanyahu government).

Chronic shortages

So why have housing prices skyrocketed? Shapira says that one cause is the short supply, including the lack of range in apartment sizes. An investigation showed that between 2002 and 2012, there was a gap of approximately 53,000 housing units between the number of housing starts and the number of households. Construction Ministry data shows a total shortage of about 115,000 units.

"The gap between supply and demand contributed to a significant increase in housing prices," states Shapira. His report cites a 2011 study by the Bank of Israel, which says this shortfall accounts for 37% of the increase in house prices and 75% of the rise in rent prices in recent years.

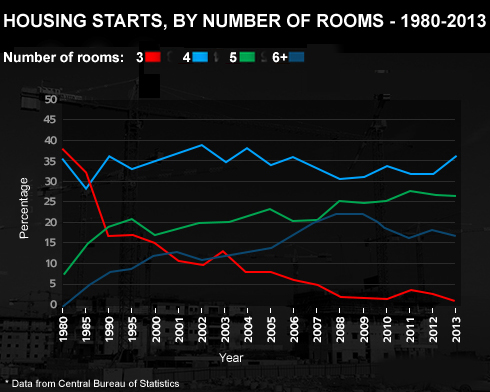

Shapira also highlighted the change in size of new apartments, which impacts on the price and affordability for home buyers. He found that only 6% of all homes whose construction began in 2013 had three or less rooms, compared with about 42% of apartments whose construction began in 1980.

The comptroller noted that the "poor supply of small apartments" throws out of balance the needs of some households and the inventory of apartments available to them. This, he says, creates "an unnecessary burden in spending on housing."

And how did the government react? From 2005-2007, the government made a series of decisions to bolster the housing market. But some of the decisions were not implemented at all and remained non-starters, Shapira writes.

"With the non- implementation of government decisions, the shortage of housing units and the lack of advance preparation for anticipated changes in the housing market that led to the start of the housing crisis in 2008, the government did not have the means to deal with the surge in house prices and deepening housing crisis," Shapira says.

Furthermore, he adds, "the lack of preparation for such crises is a fundamental flaw in the correct functioning of government."

From 2008 to 2010, Shapira says, "despite the emergence of a clear trend of sharply rising housing prices, the government headed by Ehud Olmert (who served until March 2009) did not identify this trend as a danger that demanding unique handling and did not hold any strategic discussions on the issue. Nor did it conclude that any measures should be taken to mitigate or halt the rise in prices, and never drafted a comprehensive plan to reverse this trend."

Therefore, he continues, "from 2008 to 2010, the gaps in supply and demand in the housing market grew and house prices increased by about 36% in real terms, and along with them grew the burden of expenditure on housing."

The comptroller also levels strong criticism at Netanyahu.

"Only in July 2010, more than a year after its establishment, did the 32nd government, headed by Benjamin Netanyahu, identify the need to curb the sharp rise in housing prices, and determined that there should be a housing policy that aimed to lower the price of apartments, with an emphasis on apartments for young people purchasing their first home." But these programs did not lead to a drop in prices. "Nevertheless," writes Shapira, "housing prices continued to rise in 2011 and 2012, albeit more modestly."

Shapira also cites a lack of coordination among those responsible for housing. He found that from 2005 to 2012, ministries and other governmental branches operated without oversight from a body tasked with ensuring that government housing policy was implemented.

In addition, Shapira found that programs initiated by the Israel Lands Administration (now called Israel Lands Authority) bore little connection to needs of the market.

Procrastination and foot-dragging is described in detail across the entire spectrum. Shapira found that the average time required for approval of major housing projects is about five and a half years, three times longer than the period specified in planning laws.

The time scale in the center of the country is far worse – taking an average of eight years, or, as Shapira terms it, "four times the period prescribed by law."

The report says that "a drawn-out planning process makes it difficult to achieve the flexibility in housing supply demanded. The implementation of programs is also drawn out by years, and a dozen years go by on average between the submission of detailed plans and the completion of construction."

In his summary, Shapiro writes that adequate housing is not only a real estate term, but a basic civil need.

"The government and its ministries improperly set out a national housing policy, and in many respects, the government is working without full, reliable and relevant information, and is carrying out impromptu and unplanned actions," says Shapira.

"Many of their decisions were either not implemented or had their implementation delayed. The government failed to direct home-seekers in the center to the periphery, and there were delays in the development of the periphery."

Shapira concludes by stressing that, "dealing with the housing crisis … is of national importance, and has the power to improve the social and economic resilience of the State of Israel."