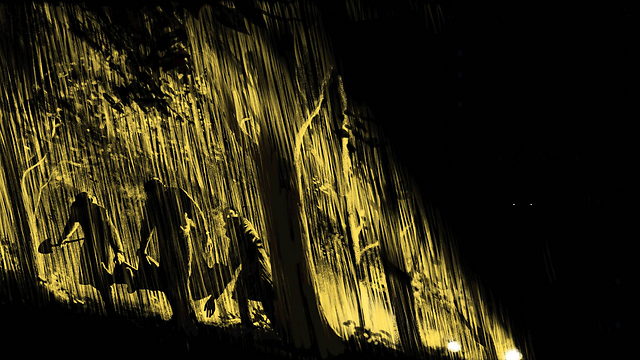

The ghosts of Saint-Germain forest

It is one of the most closely guarded secrets of the Mossad: In the mid-sixties, Israeli intelligence became embroiled in a political assassination in the heart of Paris, in a case that threatened to drag in the head of the Mossad, the prime minister and the entire country, and whose reverberations are felt to this day. Ronen Bergman and Shlomo Nakdimon are the first to open the "Baba Batra" file, and reveal those who buried the body of the exiled Moroccan opposition leader in the woods at night, doused in acid.

On a dark and rainy day in a forest near Paris, several people were digging a deep pit, throwing in the body of a man who had been strangled to death not long before. No one imagined that the ghost of the victim would haunt the Mossad for many years to come.

Ronen Bergman and Shlomo Nakdimon have re-opened the famously mysterious "Baba Batra" case to expose the unbelievable story about a kidnapping operation planned to take place at the palace of the King of Morocco, which went south and ended in an assassination in France - threatening to bring down the head of the Mossad and the prime minister of Israel.

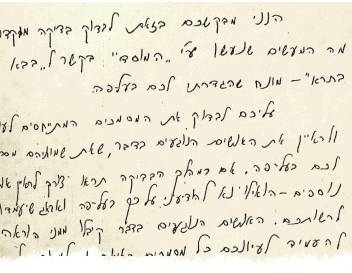

"I would ask you to hold a preliminary examination into the actions of the Mossad with regards to 'Baba Batra'- a term I defined for you verbally."

This above note was written by the third prime minister of Israel, Levi Eshkol, but it isn't in his handwriting. It was most likely written be his secretary, to whom he dictated one of the most sensitive letters in his stormy tenure as prime minister of Israel.

"You must examine the documents concerning the case and interview the people involved, whose names I gave you verbally. If during the examination you see the need to interview more people - please inform me verbally and I will make sure they are at your disposal. The people involved have received instructions from me to make all of the aforementioned documents available to you, as well as to provide you with all of the information you require of them. You are requested to write your conclusions by hand and make only one copy, which you will deliver to me.

With regards,

Levi Eshkol."

An added sentence appearing in the letter was written in a different handwriting: "We've read the aforementioned instructions and have taken it upon ourselves to follow them." Next to this sentence are the signatures of former IDF chief of staff, Lieutenant General Yigael Yadin, and the late MK Ze'ev Sherf.

This document shows the climax of one of the biggest dramas the Israeli intelligence community has ever known - and, apparently, the most serious clash between the Intelligence community and the state's leadership.

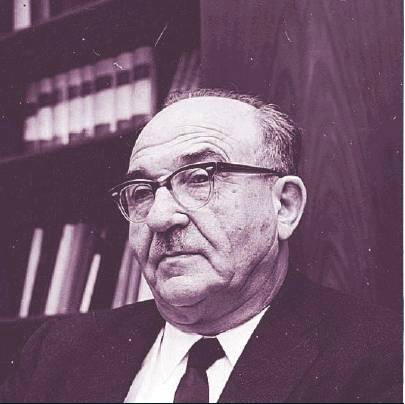

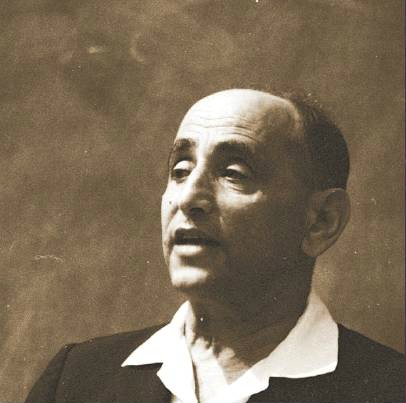

Despite the fact his name is not specifically mentioned in the document, it's clear who is at the center of the secret team's investigation: Mossad chief Meir Amit.

On February 23, 1966, the day on which Yadin and Sherf launched the investigation they were instructed to conduct - Amit was at the height of his power: He had reorganized the Mossad, created a harmonious and cooperative relationship with Military Intelligence, and executed a series of daring operations - most notably Operation Diamond, during which an Iraqi fighter pilot defected to Israel with his advanced Soviet fighter jet, MiG 21. When American experts received access to the aircraft they had longed to get their hands on for so long, Amit and the organization he led became far more valuable to them.

But it was another affair - which those few in the know referred to by the code name "Baba Batra" – that threatened to bring Amit down and drag prime minister Levi Eshkol into the abyss with him. To save themselves, the two launched a fierce battle, during which they also resurrected another highly charged Mossad affair.

The complete story of the internal war that split the state's upper echelons into two rival camps has never been told. Using secret documents from the Mossad and the Prime Minister's Office, and a series of interviews conducted by the undersigned over the years, we can now sketch out almost in full the "Baba Batra" affair.

It is an affair that started in the opulent palace of Hassan II, the King of Morocco, carried onward to a summit meeting in Casablanca and ended in an assassination in Paris - and then exploded in the halls of the Israeli leadership in the form of a dark and determined battle, the likes of which have not been seen since.

Chapter 1: The king and I

Israel, the early 1960s

The Mossad's main theater of operations was in Europe and its secret headquarters on the continent located in Paris. This, of course, wasn't a coincidence - France at the time was a great friend of Israel, and the two countries had strong security ties. The French, who were mired deep in Algerian mud and fighting Algeria's National Liberation Front - an underground organization fighting against the French occupation in the country - asked for the Mossad's help.

At first, the Mossad provided the French with information on the underground organization. Later, Mossad agents also provided weapons - sniper rifles, guns and explosives - for a series of assassinations carried out by French intelligence against the underground's headquarters in Cairo.

Despite the fact that the French later gave up on Algeria, they greatly appreciated the Israeli aid. Paris became a safe and convenient meeting point for the Mossad, even with sources who had no official ties with Israel.

"I was in favor of personal ties with the heads of the intelligence there," former Mossad chief Meir Amit told us before his passing. "I, the director of the Mossad, would go there in person to meet with them and create an alliance based on common interests."

The best pathway into Africa and Asia was at the time perceived to be through Paris, and the Mossad had become one of the most active intelligence services in these areas. The tradeoffs usually included Israeli military aid and training for local intelligence services (and sometimes ground-up construction). In return, the Mossad got approval to operate almost entirely freely in those countries, and gather information on the Arab countries and the activities of the Soviet bloc (information that was shared with the United States). Out of all these relationships, especially intimate and important relationships were created between the Mossad and its counterparts in Turkey, Iran and Ethiopia, which became a stage for intelligence coordination between the four regional powers.

But the Mossad had marked a more desirable intelligence target – one that was far harder to achieve: Morocco.

The reason is obvious: Morocco is an Arab country, which was in close contact with Israel's main enemies. But Morocco was moderate and had no territorial dispute with Israel. And it was headed by a relatively pro-Western king, Hassan II.

The intelligence relationship with Morocco began in 1960, when Hassan was still crown prince. A year later, after he was crowned, Israel asked Hassan to allow Morocco's Jews to emigrate. Muhammad Oufkir, who was in charge of the secret service in Morocco, finalized the deal with Mossad agents: $250 for every Jew who would emigrate. Funds for 80,000 Jews were transferred in bags of a quarter of a million dollars to a secret account in Europe.

Next, the Moroccans asked the Mossad to set up a VIP protection unit for them. Mossad men David Shomron and Joseph (Yoske) Shiner, David Ben-Gurion's bodyguards, were sent to execute the task. "The king was afraid of being assassinated," Shomron told us in the past. "He had enough enemies ... he was not sure of his life."

During these contacts it became clear that Oufkir and his faithful lieutenant Ahmad Dlimi were concerned not only for the king's life - but also for his rule. In particular, they were concerned about various attempts by Egypt and Algeria to undermine Hassan II. The Egyptians and Algerians had helped elements in the opposition, and the Moroccan embassies in these countries suffered repeated burglaries.

Israel restructured the Moroccan intelligence service, equipped Moroccan ships with electronic equipment to detect infiltrations by sea and provided training to prevent the break-ins at the embassies.

When a border dispute between Morocco and Algeria broke out, Amit flew - with a fake passport - to meet the king. The late journalist Samuel Segev wrote in his book, "The Moroccan Connection", that the meeting took place after midnight, in a tent near the royal residence in Marrakech.

"We can help and we want to help," Amit told the king.

The proposal was accepted. Israel gave Morocco intelligence information, trained pilots and supplied numerous weapons to the local army. In exchange, Israel received access to Egyptian prisoners who had been helping the Algerians and had been captured, and the option of training against Soviet aircraft and tanks, which were also used by Israel's hostile neighbors. Israel also established a permanent station in the capital - Rabat. This was the most important achievement.

The height of the cooperation came in September 1965. At that time, an Arab summit was convened in Casablanca, which discussed the establishment of joint common Arab command in future wars with Israel. King Hassan, who had very limited trust in his guests, the leaders of the Arab world, allowed the Mossad to closely monitor the conference.

Members of the "Tziporim" (BIRDS) unit - led by Zvi Malkin and Rafi Eitan – went to Casablanca, and Moroccans sealed off for them, under heavy guard, the mezzanine level of the hotel. On the day before the conference, King Hassan ordered the Mossad to abandon the site, for fear of encountering Arab guests. "But immediately after the conference they gave us all the necessary information and did not keep anything from us," Rafi Eitan said.

This information was of great importance: It offered a glimpse into the mindset of Israel's biggest enemies. At the same meeting, it later emerged, commanders of the Arab armies reported that their forces were not prepared for a new war against Israel.

The intimate, detailed and accurate information transferred to Israel from the summit in Casablanca about the shaky state of the Arab armies was one of the foundations for the confidence felt by IDF chiefs when they recommended that Eshkol government wage war two years later - in the 1967 Six-Day War.

One of the accounts relaying the "Baba Batra" affair states that "this sensational material was one of the highlights of the achievements of Israeli intelligence since its foundation."

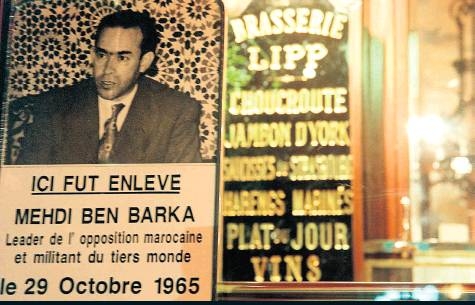

But in the intelligence world there are no free gifts, and soon after it became clear that the Moroccans wanted the debt for the information repaid as soon as possible. The target was none other than the king's sworn enemy: opposition leader Mehdi Ben Barka.

In Israeli intelligence codes, he is usually denoted by the letters "BB". Hence the nickname given by Levi Eshkol, who liked to quote religious sources: "Baba Batra" - the Talmudic tractate on legal responsibilities.

Given the damage that this affair was about to cause - it was the perfect name.

Chapter 2: Kill Mehdi

Mehdi Ben Barka was an influential leader in Morocco and the Arab world. As a leftist, he backed the revolution and the fight against colonialism, and was one of the fiercest opponents of King Hassan II. At the beginning of the 60s, he was exiled from Morocco, and later sentenced to death in absentia. At the beginning of his exile, Ben Barka and Israel established secret relations.

Dr. Yigal Ben-Nun, an historian who has for many years studied the relationship between Israel and Morocco, reveals that, "Ben Barka had a close relationship with Israeli officials, and had great admiration for the country's achievements in the fields of agriculture, regional development, and of course the military."

According to Ben-Nun, Gold Meir also sent Ben Barka a messenger, a senior member of the Mossad, and during their meeting, the Moroccan revolutionary stunned those present when he asked for money and weapons to seize power in Morocco.

"Following the meeting, Israel shied away from direct contact with him, but the World Jewish Congress gave him, with the encouragement of state officials, a monthly payment as personal assistance during his exile in Paris."

Moroccan officials never knew of the secret connection between Ben Barka and Israel, and it is doubtful that it would have changed anything. To them, Ben Barka was the enemy.

After he was exiled, Oufkir and Dlimi tried to locate Ben Barka, but he was careful to conceal his location, moving from place to place using pseudonyms. Oufkir and Dlimi decided to contact Morocco's new friend, Israel, and ask it to help track down the king's enemy.

"The request to help them get rid of the object, for them, sounded natural," then-Mossad chief Meir Amit later recalled in an interview with us. "You have to remember their value system is completely different from ours. We faced a dilemma: either help and get drawn in - or refuse and endanger the national achievements of the highest order. The decision was clear and unequivocal: to be true to our principles and not get involved in helping directly, but to incorporate it into our regular joint activities with them ... And so we acted responsibly and did not cross the line we had set for ourselves. Everything was smooth and untainted."

The first task for the Mossad was to search for the man the Moroccans had had trouble finding. From information that reached the Mossad it was discovered that Ben Barka had a subscription to foreign magazines, including the British Jewish weekly, "The Jewish Observer".

As he moved around the world, Ben Barka used a kiosk in Geneva as his postal address, and occasionally used to visit the place to pick up the mail that had accumulated there for him. The Mossad gave the kiosk address to Dalimi. All that was remained for the Moroccan agents was to observe the kiosk 24 hours a day, for two weeks, until their target appeared.

But for the Moroccans, Israel's debt had not yet been paid. On October 1, 1965, they requested Mossad agents in Paris to rent them a hiding place and provide them with camouflage, makeup and fake passports. In addition, they wanted Israel to follow their target for them and advise them on how best to send Ben Barka to meet his maker.

According to the protocol of the meetings between Amit and Eshkol, only on October 4 did Amit report to the prime minister about the Mossad's involvement. To sweeten the pill of what he was about to tell Eshkol, Amit began with the good news, describing the valuable intelligence gathered by the Mossad at the summit in Casablanca. "I want to show you the information about the debates," Amit told Eshkol, and said that intelligence indicated that at that time, the armies of the Arab countries were not ready for war against Israel.

Then came the less good tidings: "What do they want?" Eshkol asked. Amit continued: "A very simple thing: Deliver Mehdi Ben Barka. We found him in Paris and King Hassan gave an order to kill him. They came to us and said: 'We do not want you to do it, but help us.'

"Ultimately, we agreed not to give direct assistance to the killers, but to help as far as is customary in the context of cooperation between intelligence services."

Meir Amit, in a conversation with us, said: "The entire process was brought to the prime minister. The prime minister was reticent - like all of us involved in the dealings of the Mossad, he did not jump for joy - but he definitely gave consent and did not reject the plan of action."

At this early stage, the Mossad chief considered the possibility of Israel "fucking about" on the issue, in other words, buying time in the hopes that the problem might dissipate on its own. "It could have meant calling 'Baba Batra' to tell him to run away."

The Mossad provided five foreign passports, which could be used to carry out the operation undetected. The aim was to provide assistance, but keep a certain distance, so that even if the assassination failed – it would be not possible to locate the origins of the passports.

The prime minister was uneasy. "It does not smell right me," Eshkol said in Yiddish.

Amit: "Nor to me."

Eskhol: "We already agreed once that enough is enough."

Amit: "I will not take a single step without notifying you ... The problem is how I get out of it, not how I got into it. The Moroccans cannot do it, it's not simple ... I wanted you to know that ... On the other hand, there is no doubt that we also cannot show (the Moroccans) that we are evading ..."

At the meeting, Amit repeats the fundamental statement that in his opinion, if Israel is involved in any type of assassination, it should be done by the Mossad and not foreign agents. "I told our guys clearly: Don’t do it, but if you do it, it should be Hebrew labor (done only by Israeli operatives). A half-hearted approach will not work. And then the conclusion reached was not to do it."

Four days went by. On October 8, Amit told Eshkol: "So far, all is well. We are able to hold on. We are 'fucking about' on the issue."

But the Moroccans had no intention of "fucking about" on the issue. On October 12, Dlimi asked Israel for fake car license plates and poison. Israel rejected the request for the license plates and suggested the use of rented cars, for which it would provide fake documentation.

On October 13, 1965, Dlimi left France to return to Morocco, and Amit took this as a sign that the entire operation had been scrapped. "Thank God, they gave up on it," he told Eshkol on the same day.

On October 25, Amit went to Rabat for a routine hearing, during which he tried to continue "fucking about" and gently suggested that the Moroccans postpone the assassination for a few months, "so their preparations would be more perfect." But Dlimi surprised him with the announcement that the operation "is already ongoing". Amit, facing a fait accompli, realized that they could no longer dally - and had to enlist Mossad aid for the operation.

What was the purpose of the operation for the Moroccans? It depends who you ask. According to Ben-Nun, the aim was to kidnap Ben Barka and then let him choose between two options: Become education minister in the government of King Hassan (i.e., recognition of the King's rule) or go on public trial for treason. Other evidence, including Mossad and Israeli prime ministerial records, show the intent all along was to end his life.

Chapter 3: Body in the woods

Two days later, Dlimi set out on a flight to Paris to oversee the operation. According to Dr. Ben-Nun's research, a senior Mossad official was waiting for Dlimi at the airport. They left the airport quickly and separately, and agreed to meet later, for reasons of caution, at Fort-de-Saint-Cloud, where they walked past cafes and talked for about ten minutes, while an operational unit from Mossad guarded them.

It was agreed at the meeting that an Israeli representative would, during the time of the operation, wait next to the phone in the Mossad's operations apartment in the event any problems arose.

The Moroccans, accompanied by mercenaries from French intelligence and local police, were waiting for the arrival of Ben Barka in the City of Lights. Indeed, on the morning of October 29, Ben Barka arrived from Geneva, equipped with an Algerian diplomatic passport.

Ben Barka rushed to Brasserie Lipp, a known meeting place on the banks of the Seine, where he was to dine with a French journalist. He did not know that the journalist was bait set by the Moroccan intelligence to lure him into a trap. According to Dr. Ben-Nun's research, this was the Mossad's idea.

At a bend in the road before the restaurant, two French policeman - both the mercenaries in the pay of Dlimi – asked him to accompany them. A stunned Ben Barka was quickly led to a rented apartment in a suburb south of Paris, where Dlimi began to torture him severely.

On November 1, when Ben Barka was still alive, Dlimi asked the Mossad in Paris to provide by the end of November 2 a toxin and two more foreign passports, shovels and "something to disguise the traces."

Previously, there were different versions of what happened then: some argued that the station chief Rafi Eitan cabled Meir Amit a request for instructions, but before a decision could be made on whether to provide or refuse the poison, the issue became irrelevant. Others argued that the Mossad complied with the request and the poison arrived in Paris, but it was no longer necessary.

Either way, in an apartment in Paris, Dlimi and some of his aides tortured Ben Barka, competing to see who would be more vicious. What began with cigarette burns, became electric shocks and ended with repeatedly forcing the victim into a tub of stagnant water, with Ben Barka on his knees.

Dlimi had not intended to kill Ben Barka, at least not at that stage, but only gather information about the underground and force him to sign a confession stating that he had intended to overthrow the king.

The late Mossad agent Eliezer Sharon replayed to us before his passing what he had heard from the Moroccans after the fact: "They filled a bathtub with water. Dlimi grabbed his head and wanted him to reveal information. Every time Ben Barka stuck his head out of the water, he spat and cursed the king. They held his head under the water a little too long, until he turned completely blue."

David Shomron, who was at that time the head of the Mossad station in Morocco, later heard the details about what happened in that apartment from Dlimi himself. "He died in the apartment. They were torturing him in their own way: Dipping his head in a bathtub filled with water, and checking his tailbone. When it (the tailbone) began to stiffen, they took his head out. What happened is that they skipped the test, and when they did check, it was too late."

When Ben Barka did not wake up after the last submersion, the Moroccans panicked: What would they do with the body of a known Arab leader in Paris? "When he died," recalled Eliezer Sharon, "the Moroccans wet their pants."

Following a frightened phone call from Dlimi, the Mossad sent an operational team to the apartment where Ben Barka had been killed. According to Ben-Nun, a number of people arrived at the Paris apartment with two cars of bodyguards. The group climbed the stairs to the apartment, went into the bathroom, wrapped the body and put it in the trunk of the car.

Members of the group recalled that there was a forest in the immediate vicinity used for family picnics, and decided to leave the body of Ben Barka there. They drove towards the Saint-Germain forest. They reached it at night, accompanied by guards, dug a deep hole in the ground and buried the body, after which they scattered chemical powder all over the area, which was designed to consume the body and is particularly active in contact with water. Heavy rain fell almost immediately, so there was probably not much left of Ben Barka a short while later.

Three years later a road was paved at that spot. Ben Barka, it is argued, is buried under one of the traffic islands there.

The Mossad provided Oufkir, Dlimi and other Moroccan agents forged passports to leave the country. They feared that if their official passports showed that they left France shortly after the disappearance, they would face a storm from the opposition.

They were right.

Chapter 4: Isser's bomb

The French team who participated in the operation very quickly leaked to those close to then-French president Charles de Gaulle that the Moroccan security services had abducted and murdered the political leader in the heart of Paris. The French president reacted furiously: He fired a large part of the leaders of his country's intelligence services, dismantled the SDECE, France's foreign intelligence agency, and demanded that King Hassan hand over Oufkir and Dlimi. When the king refused, de Gaulle severed diplomatic relations with Morocco.

A French police investigation led to indictments against 13 people, including Oufkir, Dlimi and the journalist who lured Ben Barka to the meeting. Most of the defendants did not appear for trial, finding refuge in Morocco. The fallout from the operation has lasted to this day, 50 years later, when there is still a dark shadow on France-Morocco relations.

And Israel? The few who knew of the Mossad's involvement in the affair at first thought that the storm had passed them by. The Mossad had offered "minimal technical assistance", according to a telegram sent from the Mossad station in Paris to Amit. On November 5, Amit told Eshkol: "The Moroccans killed Ben Barka. Israel had no physical connection to the act itself".

The report Amit gave Eshkol was accurate, if one only looks at whose hands actually killed Ben Barka. It is a partial description, or at least evasive, when one considers the entire incident. However, at the same time, Amit believed the affair was behind them.

In his summary he wrote: "The situation is satisfactory ... If mistakes were made here and there, (they) were not due to inattention, but because there was no way to predict what would happen. The people in the field, who worked under the pressure of time and in the most difficult circumstances, made some mistakes, and I take all the responsibility upon myself. Despite the errors, we are still within the security boundaries we set ourselves ..."

On November 25, 1965 Amit told Eshkol: "Everything is fine."

Amit had forgotten that troubles did not always come from outside. Sometimes they erupt internally.

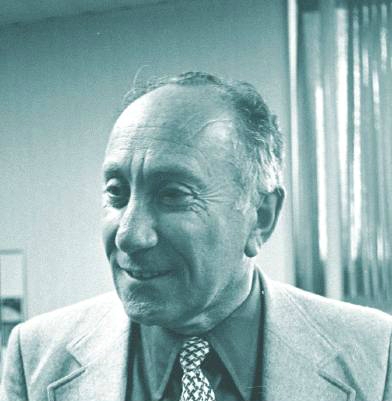

This is where Isser Harel came in.

Harel, known as the "father of Israeli intelligence", and who saw himself as the sole of the owner of the Mossad, had been forced to leave his post as Mossad chief following a dispute with David Ben-Gurion. Later, as a form of compensation, he was appointed as intelligence consultant to prime minister Eshkol. Many argue that at this stage Harel was bitter and looking for an opportunity to show that his successor at the Mossad – Meir Amit – was not worthy of stepping into his shoes. And what better opportunity could he have than the well-publicized murder case in Europe?

When Harel heard of the Mossad involvement in the affair, he turned to prime minister Eshkol. Before his death, Harel described the situation to us: "I told him (Eshkol): 'God sent me to protect you and you became terribly entangled. Amit lied to you all along. You told him not to get involved (in the Ben Barka case), and he was involved. This is very serious situation ... And it heightens your own responsibility, and now you have to resign.'

"Eshkol really begged for his life," Harel recounted. "I told him, in my opinion, you should appoint a commission of inquiry and see who is responsible for this failure, and the findings of the investigation will decide whether you continue as prime minister. And as for Amit, you should know that he did not tell you the truth. You had an advisor (referring to himself) and did not use him. Eshkol almost started crying ..."

Meir Amit, in a conversation with us: "As soon as he (Harel) took office, he began to undermine and to prove that his replacement (Amit) was inexperienced and irresponsible, and actually operated by foul means, taking advantage of his past connection to the Mossad... When he discovered the affair in question, he leapt on it like a treasure, and decided that it was the way to achieve his desired goal: to eliminate his detested successor."

Adi Yaffa, the head of Eshkol's bureau, recounted to us in an interview: "Harel turned to Eshkol and said: Either you fire the head of the Mossad, or you must resign yourself. Eshkol replied that until the crime was revealed, he would not get fire anyone. An error can be corrected."

On the one hand, Isser Harel; on the other, Amit and Eshkol. The fire began to spread in the corridors of the government, the big secret was whispered by word of mouth, and soon it developed into a massive internal conflict.

Harel demanded and received from Eshkol the documents on the "Bava Batra" affair, and sat down to write a serious report about it. In a letter attached to the document, Harel wrote to the prime minister: "As I informed you already orally, the Mossad, and through it the state, were engaged in various actions connected to a political assassination, in which Israel not only had no interest, but should not have, I believe, from a moral, public and international perspective, been involved in at all."

Regarding Amit he wrote that, "he has seriously exceeded his powers ... he used bad judgment ... his report was partial, incomplete and misleading; to this day he has not reported the role of the Mossad. In light of all this, I expressed my opinion to you and to the justice minister, that it is necessary to conduct an urgent and thorough investigation of the affair, and immediately propose the establishment of a commission of inquiry."

The entanglement caused in this case was a very serious issue. In addition to Israel's involvement in the matter, no consideration was given to the danger of illegally aiding the Moroccans to carry out a criminal act on French soil, which harmed the laws and sovereignty of France and caused serious risk to its relations with Israel.

Years later, when we asked Meir Amit about the extreme accusations hurled at him by Harel, he said: "No action was taken that endangered or implicated Israel. The matter was leaked by Isser Harel, who behaved with a lack of national responsibility out of personal interests of burning jealousy. He was not driven by concern, but by unbridled vengeance."

Chapter 5: The wars of the Jews

The storm around the affair gave rise to a number of committees and secret forums set up to investigate the chain of events.

One of them, in an unprecedented way, comprised a group of senior officials from Mapai (the Israeli Labor party's forerunner), who declared themselves a committee and supported Harel. The late Mordechai Nessyahu, a senior Mapai member, recounted to us in the past: "Isser gave them (the committee members) his conclusions. He concluded that Israel should never have entered into it (the operation). It was an error of judgment by Eshkol. The entanglement was the responsibility of Amit, and, contrary to his promise, there were complications.

"The committee unanimously concluded that Amit had to go. We also made the recommendation that Isser go to de Gaulle and tell him, lest the affair was discovered and caused us trouble, but Israel drew its own conclusions and those responsible are now gone."

Several senior Mapai members turned to Golda Meir. "She knew everything," recalled Nessyahu. "She agreed with the political and moral severity of the matter, and that Amit would have to go ... we said Amit did not interest us. We did not deal with civil servants, but with the political responsibilities of the prime minister. No conclusions were drawn... we told her, 'we have to draw conclusions with respect to Eshkol'."

Golda: "Who?"

Us: "You"

Her: "I will topple Eshkol, and take his place? I would rather throw myself into the sea and will not do it."

In order to satisfy those inside the government circles, Eshkol appointed another committee to examine the events in Paris. Its members included two good friends of Eshkol, former chief of staff Yigael Yadin and Ze'ev Scharf, who would be appointed minister in the future.

The external committee determined that in several instances Eshkol was not briefed by Amit or received late updates. For example, the committee wrote: "The meeting with Albert (Dlimi's nickname) on October 25 (in Morocco). At this meeting Albert announced that he had his own process (the operation to abduct and eliminate Ben Barka) that should yield results by the end of the month. At this stage, he only needed technical support. Shah (Rafi Eitan's nickname) also asked for these measures and was promised them. When we asked the head of the Mossad about this promise, that had not received prior approval, he explained that he acted according to standard procedure. Incidentally, these measures were not used and were returned. There is no record that the prime minister received a report about this meeting."

However, the committee - not surprisingly - determined that Eshkol had actually approved the Mossad involvement in the affair, and that the actions of the two were fundamentally correct, and there was certainly no reason to oust the head of the Mossad or the prime minister.

Harel did not like these conclusions. "When I read the conclusions of the committee," he said during a conversation we had, "I told Eshkol: 'Do you not know that Amit is deceiving you and you have to quit?' However, I also told Eshkol: 'You have a way out. Say that you will set up a judicial investigative committee. Without it you will have to resign.'"

Harel launched an all-out war, in which he implied that "the echoes of the affair will come to the attention of the public and the entire party (Labor) will be tainted with the shame."

A senior officer in Military Intelligence, who was never interviewed by the media, recalled that the threat to Eshkol's rule was so great at the time, that a very senior IDF officer entered Amit's office at the Mossad headquarters, laid a gun on his desk and said that Amit should "end the affair in a manner expected of an officer." Amit, according to this story, "did not get the hint" and returned the gun to its owner. The source of this story said that he had heard it from the officer who laid the gun on the table and that he believed him, but was not actually witness to this terrible moment. We found no additional references to this particular story.

Either way, it is clear that these were hard times for the Mossad chief, who found himself up to his neck in the assassination and subsequent efforts to cover it up. When we asked him, Amit, who used to elaborate greatly about his feelings, summed it up thusly: "I felt frustrated and under great pressure."

Chapter 6: Striking back

At a certain point, when Harel's harsh attacks did not subside, Eshkol and Amit decided to fight back in similar fashion – using a secret affair that could cast a shadow on Harel. Amit told his close associates: "He (Harel) will not drop the subject of his own accord ... unless it is hinted to him that in his past there is enough material to undermine his claim that he is 'the moral guardian' of the Mossad."

And there was indeed "enough material". They were referring to a case, first disclosed by Ronen Bergman in Yedioth Ahronoth in 2006: In 1954, then Mossad chief Isser Harel sent his people on their first overseas assignment. The goal was to kidnap an IDF officer in Paris, who was suspected of trying to sell secret documents to Egyptian intelligence and return him to Israel for a trial. Somehow, the kidnapped man died en route to Israel, and, on Harel's orders, his body was dumped at sea. Harel also gave the order to hide the documentation of the affair deep in one of the Mossad’s vaults and to never discuss the matter again.

But there was one man who whispered the details of the affair into Amit's ear, when he replaced Harel. When Harel's pressure on Amit to resign grew, Amit recalled that he too had a card up his sleeve.

Amit demanded the file on the kidnapping and passed it to the person acting on behalf of Eshkol in the affair. That person summoned Harel for a meeting.

"What do you think would happen if the echoes of this affair caught the attention of the public?" the man asked Harel. "Isser, don't you think that such a serious matter certainly requires a thorough examination and intense investigation? Of course we will keep the story quiet, but we are not the only ones who know it, and it's truly outrageous, the things that come to the attention of journalists these days."

"I was the one who demanded a thorough investigation at the time," Harel said angrily to the man, and repeated this in a conversation with us, 30 years later. On the other hand, Harel understood all too well what would happen to him and his reputation if he continued to pursue his interest in Ben Barka. Shortly afterwards, he resigned as intelligence advisor to the prime minister.

Isser Harel has a completely different version of the circumstances of his resignation, and claimed that it was in response to the conclusions of the committee of inquiry on the Ben Barka affair and Eshkol's refusal to fire Amit.

Meir Amit is unconvinced: "Harel did not resign for reasons of conscience over the incident in question," he told us, "but because it was implied that if he continued to stir the pot, there was a serious risk for himself, as he had been involved in questionable incidents, and his 'righteousness' would be destroyed ... He resigned when we put the file on the murder of Jews on the table."

Military censorship imposed a media blackout on the Ben Barka affair, and in December 1966, the editor of the yellow magazine "Bool" was arrested and imprisoned for trying to publish the little he knew about the affair. But in France - despite the fact that books have been written, movies made and documents revealed about the affair - it is repeatedly revisited every few years; a wound that cannot heal.

In 1973, Oufkir was shot dead with one bullet, either by suicide or murder, after being exposed as part of a conspiracy against the king. According to one version of events, he died in a gunfight that broke out between him and Dlimi. The latter was that he was killed in 1982 in a car accident, which, according to assessments, had been staged.

French intelligence suspected at the time that Israel was involved in the case, but made no great efforts to find it due to its support for Israel. But when the IDF launched its surprise attack on Israel's neighbors in June 1967, de Gaulle responded sharply and ordered an absolute arms embargo.

In an extreme speech he delivered in November of that year to the French parliament, de Gaulle said the Jews “at all times (see themselves as) an elite people, sure of themselves and dominating.” Two days later, he ordered the expulsion of Mossad's representatives in France and the closure of the organization's headquarters.

It was the first time that the Mossad had been thrown out of Paris because of the assassination.

It was not the last.