Until I actually met them two months ago, inside a nearly-empty auditorium in the middle of the summer semester, I too thought they were just an urban legend.

About half an hour before class started, the door suddenly opened and two tall guys entered. They didn't notice me. They saluted each other and walked in perfect sync toward the front rows. I immediately noticed that something about them was strange – even though they looked Korean, they didn’t dress fashionably and were abnormally quiet, unlike the average South Korean.

When one of them moved his hand, I noticed he was wearing a red pin with a familiar face on it – the late Kin Il-sung – founder and former leader of North Korea.

A week later, I noticed one of them in the library, by himself this time. "North Korea, right?" I asked, and he smiled. "Israel?" he opened his eyes wide in surprise, giving me his first human response, "If I am to be honest," he mumbled, "I don't think very good things about Israel".

Ironically, I would later learn that "to be honest" is one of the few English-language sayings almost every North Korean knows, along with the less basic but more often used "great leader". Simpler words like "family" or "water" are entirely foreign to most of them.

When I told him I lived in South Korea for about six months he couldn't hide his enthusiasm. "What does Seoul look like?" he asked, his eyes gleaming with curiosity, and eagerly took in an hour's-worth of stories about the vibrant country's accelerated development.

But the conversation was interrupted by his companion, and he didn't look pleased. My conversation buddy went silent, the two left immediately and from that moment on weren't seen on campus again.

When I tried to find out where they went, the mystery grew. "We had one student," admitted Debra, who was responsible for the university's student exchange program, "but he left in the middle of the semester. He said his father was sick and that he had to go home." She then added that he was the son of a "very high ranking" member of the communist regime, who came to Hong Kong to study international relations. She was surprised to hear about the student who accompanied him to each and every class.

Later, I would learn that the other student was actually an official government chaperone, protecting him from being exposed to western culture, and also making sure he doesn't reveal too much of what happens inside his country.

A few weeks later, when I got the chance to join a delegation that would visit North Korea, I had no doubt that I'd go there and try to understand how the country manages to control its people like that.

Ever since Kim Jong-un (son of late leader Kim Jong-il, and a ruthless dictator himself) became supreme leader of North Korea, the country has been surprisingly open to outside tourism, and has declared bringing in 1 million tourists a year as its goal.

Thart doesn't mean, of course, that you'll be able to travel freely: At any moment, three guides will be following the curious visitors, step by step, and when you leave the immigration clerks will thoroughly check every one of your selfies.

But ignoring all that, we see that North Korea is like many other countries you can visit – you can by a Lonely Planet guide there (which includes "do" and "don't do" instructions), read people's reviews on TripAdvisor.com (forget coffee for breakfast), and search for hotels on price-checking sites (just don't expect too wide a variety).

Even with the recent tendency toward openness, the border policy of North Korea still changes according to the leader's whims, tourists are limited to varying lengths of stay, and they only get to see a small number of pre-approved destinations. The identity of the tourists also matters: Chinese visitors (the government's favorite nationality) are given many reprieves and are loosely monitored, while at the other end of the scale are the two most dangerous groups of people: Journalists and South Koreans.

And if you did manage to enter the country, here's an important tip: don't make any comment distinguishing North and South Korea. The North Koreans see them all as one nation, and anyone who claims differently will be swiftly scolded. But while local propaganda might celebrate the upcoming reunification day of "our nation", in practice the government people and other elites will admit that, for them, the day South Koreans walk these streets will be a dark one.

The elites know that when workers find out that their salaries are 40 times lower than those of their southern colleagues, they'll revolt. The two countries share the border with the highest income disparity in the world, and that's why it stays hermetically closed. Every interaction northerners have with southern members of "our nation" is considered treasonous.

Trying to avoid the restrictions that journalists are usually put under, I stated that I was a student. Happily, my passport was returned to me a few days before the trip with an approved visa. Not long after, my joy mixed with worry when a short Google search reminded me of the story of two American journalists sentenced to 12 years' hard labor in 2009, after they tried to enter North Korea with tourist visas.

"You don't really concern them," said the trip's organizer, calming me down. "They don't have the means to follow everyone, and they direct most of their efforts inward - to control the population and limit the information they can get. Their image in the world is secondary to their internal image." 24 hours later, I stood on the boardwalk of the industrial city of Dandong, China, watching the darkness on the other side of the Yalu river.

The clash of civilizations was right in front of me. On one side, a fortified and secluded country, perhaps the last refuge of real communism in the world. On the other, a well-run capitalist show, the likes of which only the Chinese machine can produce. The souvenir shops were full of tourists, who had to stay inside them for at least 20 minutes per their vacations packages. Looking at their full shopping bags, it didn't seem to bother them. The tourists are mostly Chinese, but there were also a few South Koreans, looking to take a photo from as close to the northern neighbor's land as they can get.

The two civilizations are connected by the China-North Korea Friendship Bridge, which crosses the Yalu sewage and mud swamp, erroneously called a river. Unofficial reports say that thousands of desperate North Koreans attempt to cross the Yalu every year and escape their iron rulers. Unfortunately for them, it's suicide. Even if they manage to avoid the Chinese authorities, which tend to extradite them right back to North Korea, the polluted river's waters will take their toll.

The bridge itself is owned jointly by both countries, a fact that becomes clear at night, when one side is brightly lit with colorful bulbs while the other stays completely dark.

But the North Koreans aren't suckers – they have a real park on their side, nicknamed "No Man's Park" by the locals. When the train crosses the border and allows for an up-close look, you see why: You wouldn't want to ride this giant, rusty Ferris wheel, and neither would the locals. That's why the park has stood vacant since its establishment.

Movement on the bridge is fairly lively. While dusty Korean trucks make their way to Dandong to stock up on Chinese cargo, the other side of the bridge sees a convoy of mini-buses loading tourists on, ahead of their Pyongyang vacation.

North Korea is entirely reliant on the Chinese giant, which is the isolated country's nearly exclusive trade partner. From the Chinese perspective, South Korea is capitalistic, and thus subject to influence by the United States. That's why China smothers the North in a big bear hug, and continues to stop it from opening to the world by showering it with more than half of its foreign aid budget every year. China is, in fact, the real reason behind North Korea's continued isolation from the world.

The show must go on

"Number nine!" the Korean immigration clerk pointed at me when he entered the train car, asking me to open my bag. "Shui," ("water" in Mandarin) he whispered to me, miming a sipping motion. I gave him my bottle, he sighed and drank. Then he asked if I had a camera, and when I said I didn't (elegantly ignoring my iPhone), he went on to the next tourist. So easy. Maybe too easy. Exiting the country later involved a similar procedure.

With local guides waiting at a six hour ride's distance, nothing could hide, or distract my attention from, the sites outside the train's window. There, I'd find a country that looks like it's frozen in time.

We pass by farmers relying on pitchforks and cow-harnessed carriages, cows that become thinner and thinner the farther we get from the border. When the train passes, the farmers stop the hard work of plowing the corn and rice fields for a moment. It might travel daily, but the locals still marvel at this wonder of Chinese technology, which they will probably never get to ride. Freedom of movement is a privilege here, and each journey from place to place demands special approval.

The time is 2pm, and the train stops suddenly, in the middle of nowhere. North Koreans, it turn out, take their lunch break seriously, and train workers deserve some rest too. In the fields outside the window, the farmers sit in circles and eat lunch together, and we also get a meal on a pre-packed tray. I can't finish it. In the cabin next to mine sits a young woman, a red pin on her lapel. I offer her my tray. She refuses awkwardly and points to a nearby garbage can. When I walk by an hour later, there's no trace of the tray, and a quick peek into the other cabin reveals the young woman digging into the sticky rice I threw away with her chopsticks.

Her Name is Jim Kim Su, she’s 31 years old, and, using hand gestures and gibberish, she explained to me that she lives in Pyongyang with her husband, a doctor, and their five year-old son. After I taught her to count to ten in Hebrew, Su answered a phone call, displaying a shiny Arirang smartphone, available to one out of every 12 local citizens. After we immerse ourselves in an intense game of Angry Birds, the ticket inspector notices the sounds of laughter coming from our seats. One look from him is enough for her to get up and move to another cabin. When I passed by her later I saw that her face was frozen. It was my first time meeting the North Korean fear machine.

In first class, I meet four athletes coming back from a sharpshooting contest in Germany. “We did all right,” one of them says with a smile, not elaborating. North Korea worships its athletes, and they get to live in very comfortable conditions – including fancy apartments in the middle of the capital and frequent trips overseas.

One of the four, who spoke fluent English, even told me that he experienced the highest possible honor in one reception, standing just a few meters away from the great leader. I accidentally touched his lapel pin and was immediately rebuked: “Careful!” By law, North Koreans must take care of the pin featuring the leader’s face, as well as his portrait photo, sent to every house in the country each year.

“Have you ever eaten at McDonald’s?” I asked. “No, but as I understand, I’m not missing much,” he smiled. “And what’s your favorite Korean food?” I asked. “Kimchi,” he answered, meaning fermented vegetables with a variety of seasonings. “And the drink?” “Soju”, he named the country’s most popular alcoholic beverage. “The government even gives out bottles on special occasions, like the leader’s birthday.”

We continue talking in relative freedom, but every time a bystander passed by us he spoke up, throwing out an anti-American sentence. After the danger passed he went back to his normal tone of voice.

“You talk with hatred about America, but hold a Coca Cola bottle in your hand,” I say. “It’s not the products and it’s not the people – it’s the governments," he answers, "We hate the American government, but I have friends from the US and I like their politeness. I also meet many Israeli athletes and it’s clear that on a personal level I don’t have a problem with them, even though, to be honest, I don’t have a positive opinion regarding Israel. I hear on the news that you’re firing rockets. Like us, you suffer from having an evil image in the world."

On the bus ride to the next destination we meet our tour guides, Ms. Lin, Ms. Jin, and Mr. Lee, for the first time. Mr. Lee sits next to me. As the only Westerner in the group, I've been marked as a potential troublemaker and am closely accompanied throughout the trip. They even make sure that I bow to the statue of the great leader.

Unlike the two female guides, Mr. Lee didn't speak much, and if it wasn’t for the risk he took by taking me to a local bar the next night, I would've been convinced that he was an undercover government agent. But there, over a glass of Chivas, I learned that when it comes to sensitive questions, he chooses silence over lying. He asked about average salaries in Israel, the plastic surgery market in Seoul, and most importantly – wondered if I could get him any hand sanitizer.

It's a legitimate request in a country where running water is a rich man's privilege. For example, while a maintenance man waters the gleaming lawn around the luxurious "Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum" (our guide adds, "which was built in just ten days!"), the line of locals gathering water from a nearby pump stretches long. North Koreans generally divide into two classes: Those carrying jerry cans, and those carrying black briefcases – the status symbol of the upper middle-class.

And what's my status there? Let's just say that Mr. Lee refused to introduce me to a local beauty sitting beside us at the bar. "It will never work," he said, laughing. "We don't mix. We're a homogenic country and preserving racial purity is important to us."

A snotty welcome

The Yanggakdo Hotel, where we stayed, is located on an isolated island in the middle of the Taedong river which crosses Pyongyang, and is meant for foreigners and rich locals only.

This "Alcatraz of fun", as it's nicknamed by tourists, offers attractions like a spinning restaurant on the roof, a casino, a bowling alley, snooker tables, and a swimming pool. The TVs in the rooms have access to BBC and Al-Jazeera, but occasionally these are blacked out, probably during reports about a certain country.

Want to tell your friends at home about your experiences? The fact that the country's people don't have internet access doesn't stop the hotel from putting an emailing computer in its entrance. You'll need to recite it to the typist, who'll make sure to run it by the censors first.

Luxury and poverty intersect here as well: From the creaking elevators that stop on dark floors, through the fancy porcelain taps that don't spray out any water, the empty trays at the breakfast buffet, to the rotting apples at the prestigious superstore.

The next day, we travel to an elementary school, two hours' distance away from the capital. Jin tells us that today is a national holiday – child day – and when one of the students asks why the school is open on a holiday our guide answers with surprising honesty. "The teachers and students were asked to report because a group of foreign tourists are coming to visit."

"And what about the people in the blue jumpsuits mining rocks by the side of the road," I point out, "are they here for us as well?" She says "They are volunteers," and doesn't go any further. We join in on an English class, and I ask to swap in for the teacher.

Where am I from? Israel, do you know it? "Of course."

What do they think of us? "Not good, war."

Where is Israel on the map? They point at Yemen.

Where in the world would you like to travel? "Egypt, the Pyramids."

One of the students asks, "And what about the United States?" Ms. Lin then quickly interrupts, saying "Okay guys, we have to go, the children have many more classes today."

Even though our next destination is in the school's vicinity, we go all the way back to Pyongyang for lunch. Restaurants, after all, are a rarity outside the capital. "I'm starving!" said Ms. Jin. Realizing the irony in what she just said, she giggled awkwardly. Estimates say 3.5 million North Koreans starved to death during the 1990s, and hundreds of thousands are in similar danger today.

It's doubtful if the return to Pyongyang was a wise decision by the guides, because right outside the restaurant's parking lot, we saw an active black market. Dozens of products scattered across the floor, with people buying and selling openly. Some of them were even uniformed soldiers, carrying bags of vegetables, coal, candy, and even South Korean cosmetics.

If not for the government vehicle that arrived a few minutes after we did, you might think that even the government had made peace with the phenomenon. "No pictures!" warned the character coming out of the vehicle, as we entered the restaurant.

Our next stop was the "Grand People's Study House" – the central library where English lessons are given to any citizen at no cost. Surprisingly, we enter in the middle of a screening of the film "Gladiator". Generally, Hollywood movies are banned in North Korea, but for purposes of teaching English some of them get special approval. "The Lion King" also got in.

I ask Insayan Kim, 31, who comes here once a week to learn English in order to help with her job as a computer technician, if she knows these are American movies. "So what?" she shrugs. Her favorite movies are "Troy" and "300", because "There's history in them. I like films you can learn something from, and that's why I like our local films, that are meant first of all to send a message, to educate people."

I ask her about romantic movies. "We don’t have things like that here," she answers. "If there's a romance between a man and woman, it will always come to serve a larger love story, between the citizen and the state and its great leader."

At the book stand, we're presented with a fossilized copy of "Gone With the Wind". A look at the ticket shows that the last time it was taken out was in 2012. The tables in the music room have double-cassette radios from the 90s.

The librarian promises us that everything here is "made in the Republic." I turn one of the radios around and see a sloppily slapped-on sticker covering the familiar Sony logo. Workers have prepared tapes for us with some Cantonese hits, probably trying to play to the crowd's tastes. When I ask if they have any Western hits they tell me that there's a Beatles copy, but you have to order it several days in advance.

Ms. Lin's face shines when she tells us that our visit to the famous Pyongyang metro was extended, and that we'll get to see "not one, not two, but six different stations!" As opposed to other destinations in our tour, the metro ride is a real opportunity to interact spontaneously with locals. In the fourth station, I witness the state's fear mechanism once again.

In one of the packed cars, I sit across from an older, friendly-looking man. He's wearing a white hat that features the words "Made in China." I point to the words and then to my colleagues, and say that we're also "made in China." A young woman sitting by the man translates to him, and a smile spreads across his face, and then to the rest of the train car.

Suddenly, a young man gets up from the other side of the bench and takes away the old man's hat. He points at the writing, points at me, spits out some words in Korean and throws the hat back into the man's lap. God forbid a foreigner notice a Korean wearing something with another country's writing. The embarrassed grandpa looks scared and hides the hat between his knees. He gets off at the next station. The man who screamed at him wasn't a soldier or police officer, just a regular citizen, who smiled at me a minute earlier.

Making things right again

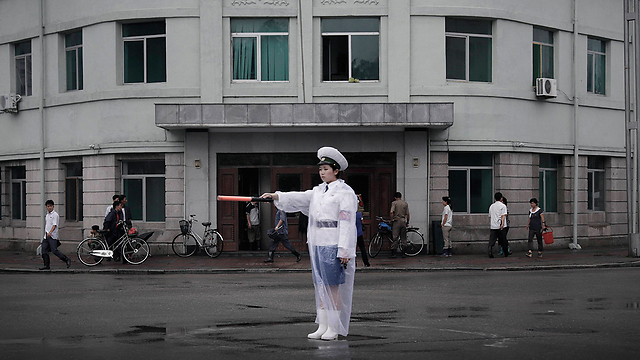

Wherever they go, North Koreans are obligated to act in a properly representative fashion. They're required to have a military haircut – one of 14 approved by the government. They aren't allowed to display joy and happiness even when they're at the amusement park, in one of the bumper cars, eating a piece of stale bread in lieu of cotton candy.

At the "Central Youth Hall", a type of Pyongyang YMCA meant to nurture young talents, we're greeted by an 11-year-old guide. Looking frightened, she opens with a salute. Ms. Lin leads us to a short recital where two young girls play the piano. The concert was flawless - each note in place, each blink synchronized, but to my surprise there was no applause in the end. When our tour group started clapping enthusiastically, the girls smiled in awkward surprise. It seemed like the first time they got any recognition for their skills.

Afterward, another Western student, himself a gifted pianist, pointed out the state of the piano keys – they looked bent, probably as the result of being hit powerfully. "A person who plays like that doesn't really enjoy what they do," he said.

In the calligraphy room, a young girl pulls a paintbrush across the canvas to create an anti-jealousy message that's derived from Juche, the ideology composed by founder Kim Il-sung. Juche rests upon the country's principle of political, economic, and military self-reliance. Thus, no jealousy is needed – we have everything, and outside there's nothing.

At the local kindergarten we meet a group of snot-nosed kids with slumped shoulders. I talk with Ms. Lin, while the kids dance in a circle, perfectly synchronized. Suddenly, a girl grabs Ms. Lin by the hand and invites her to join the dance. Ms. Lin pushes the girl away and aims an angry look at the kindergarten teacher, who's supervising it all.

The teacher immediately corrects the mistake, grabs my hand and leads me to the circle – not looking directly at me even once. She was given a task – me – and now she must follow the instructions.

Later, In Kaesong, which is in the demilitarized zone between the Koreas, it seems that both sides of the secure border know how to make the difficult situation a little more profitable. South Korean travel agencies sell different tour packages to the area, including an ecological tour between the mines and spy games in the underground mazes.

In the northern side (after the obligatory visit to the gift shop), a fierce-looking soldier will accompany you closely into the balcony, giving you a peek at the South Korean observatory across it.

When I ask Mr. Lee if he doesn't feel a pinch of sorrow when he sees the modern South Korean building, compared to the simple shack we're in, he stays quiet. Eventually he says "You know, money isn't everything in life. The south might enjoy prosperity and development, but they've lost their identity, their values, their tradition."

The border fills with tourists, but as the only Westerner around I get the most attention – including close inspection by a local propaganda photographer, who'll probably create great treats out of this "atonement tour".

"Israel?!" shouts the fierce-looking soldier when he finds out where I'm from. "You're doing to the Palestinians the same thing the US did to us! You're bombing innocent people. Israel has nuclear weapons, and so do we. What do you think of that?" he asks defiantly. "I wish the world didn't have any nuclear weapons in it," I answer. "We also want humanity to enjoy peace, but the state of the world doesn't allow it," he retorts triumphantly.

The Israel issue proves to me that Pyongyang can contain a certain variety of opinions (even if most are negative). For instance: Dr. Kumasi Lee, 28, a heritage site researcher who stayed in the room adjacent to mine in the traditional Korean hotel where we spent the night after the border visit ("traditional", meaning no hot water, and no lights at night). He came to Kaesong, the ancient capital of the united Korean kingdom, as part of his post-doctorate. "So you speak Hebrew?" he asks me when I tell him I'm from Israel. "Are you from Tel Aviv?" he surprises me again.

I ask him where he got this knowledge, and he answers "I'm a scientist, and you Jews are geniuses."

In the morning, we get back on the train to China. Only after we cross the friendship bridge do I allow myself to relax and sigh. What a relief – true freedom.