About 9,300 kilometers separate Los Angeles and Berlin, and in the 1930s – long before the age of the internet, the cell phone and jet planes – the distance seemed even greater.

Nonetheless, there were those in California who had their eye on Germany, and in particular on its residents. Despite the national humiliation of World War One and the massive inflation, the country's cinema industry continued to be the most productive and developed in the world. German cinema-goers were the most educated to be found – perhaps because their love of film gave them some hope.

Germany in the 1930s had the UFA studio and groundbreaking directors such as Fritz Lang and F.W. Murnau, but many in Hollywood saw in the impoverished Depression-era German population a vast potential audience for Hollywood's output – even as the specter of Nazi Germany reared its head.

Author Ben Urwand explores the resulting cooperation in his book "The Collaboration: Hollywood's Pact with Hitler." Industry honchos made sure to not only maintain warm trade relations with the Nazis, but also to alter content in order to meet the Nazis' approval.

The most prominent residents of Tinseltown to openly oppose Nazi Germany were brothers Jack and Harry Warner – AKA the Warner brothers, descendants of Jewish Poles. The two men were notable for their early denunciation of Hitler, not only relative to others in Hollywood, but also compared to politicians.

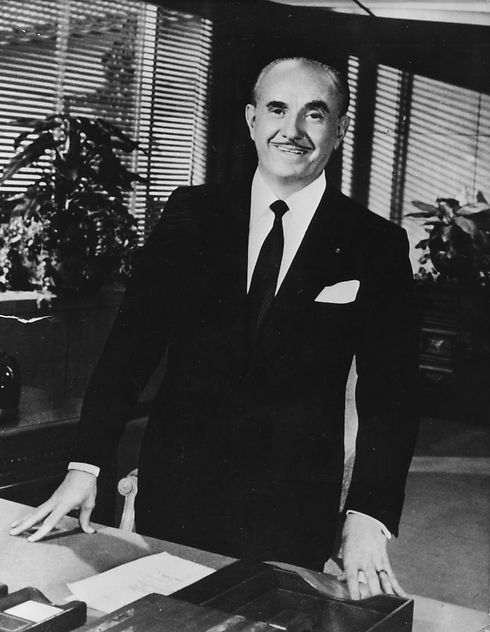

Thus the 1933 Warner Bros. cartoon "Bosko's Picture Show" featured caricatures of Laurel and Hardy, the Marx Brothers, and an axe-wielding Adolf Hitler. In the cartoon, Hitler is chasing after the American entertainer Jimmy Durante in a fictional town called Pretzel.

This depiction of Hitler is believed to be only the dictator's second appearance in American film. A few weeks earlier, he made an appearance in a cartoon titled "Cubby's World Flight". But while the earlier cartoon features Hitler as a smiling man who is friendly towards a flying bear, the Warner Bros. film clearly portrays him as a brutish bully.

The brothers' commitment to combating the Nazis became complicated when Joseph Breen, chief of the institution overseeing Hollywood's ethical codes, forbade the creation of anti-Nazi propaganda starting in 1934.

The US policy of neutrality was unacceptable to Jack and Harry Warner, who attempted to use their influence with President Roosevelt to press the issue. The brothers even offered his administration use of their studio free of charge, but were rejected. Seeing that the US was unwilling to intervene, the Warners donated funds to the United Kingdom for upgrading the Royal Air Force.

The Warners decided to oppose the Nazis by cancelling plans to purchase German studio Universum. Harry Warner, the more religious of the two, led a campaign to boycott production companies in Germany and cut all business with them.

It should be noted that the Warners were banned from Germany in 1934 as a result of the film "Captured!", whose main character is a US soldier in a German POW camp during the First World War.

Urwand also writes about a meeting with the German Consul in Los Angeles, Georg Gyssling, that led to changes in the 1937 film "The Life of Emile Zola."

The Oscar-winning film about the Dreyfus affair relegated the officer to a secondary role and obfuscated hiss ethnic origins. The same year saw the release of "Black Legion," in which Humphrey Bogart played an American seduced by fascism.

On the eve of the Second World War, the Warners launched a frontal attack on Hitler and his regime with the 1939 spy thriller "Confessions of a Nazi Spy." The film was something of a declaration of war, warning of Nazi infiltration in the United States. The thriller was the first film to portray the Nazis as enemies of the US and caused an outcry in both Germany and the US, which were not yet at war.

Although the plot was based on actual events, the Warners were told by authorities to refrain from making such films in the future for fear of diplomatic repercussions. Expat actresses Marlene Dietrich and Anna Sten both declined to participate in the film out of concern for loved ones who remained in Europe.

"Confessions of a Nazi Spy" was a major commercial success, despite being banned in Germany, Japan and several South American countries. Reports in 1940 said that several cinema owners in Poland who dared screen the film paid with their lives after the German invasion.

Alongside threats from abroad were domestic threats. Senators Gerald Nye and Bennett Clark, supporters of an isolationist foreign policy, decided to convene a special hearing in which they argued that Jewish power in Hollywood was no less problematic than Nazi power in Germany. They threatened to push for closing the Warners' studio. Harry Warner was called to give testimony and explained that the films were not propaganda but pure entertainment.

These discussions were brought to a halt after the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, bringing America's isolationist policy to an end. As soon as the US declared war on Japan and Germany, Hollywood studios joined suit, with the Warner brothers using their animation studio as their preferred platform.

A 1941 Soviet propaganda cartoon, "What Hitler Wants," was a possible source of inspiration for the US's new animated offerings.

When Jack Warner was recruited to the US war effort, the cast of Looney Tunes came with him. Their first official on-screen bout with Hitler came in summer 1942, with the release of Norman McCabe's "The Ducktators."

Recounting the experiences of a duck bearing a striking resemblance to Hitler, a Benito Mussolini-esque goose and another duck apparently representing Japanese Emperor Hirohito, the cartoon comes out as a companion of sorts to George Orwell's "Animal Farm" – albeit addressing the rise of fascism rather than communism.

In another duck-led propaganda piece, 1943's "Daffy – The Commando" features the titular hero fights the Nazis behind enemy lines.

Daffy's exploits continued in 1944 in "Plane Daffy," in which he has a rendezvous with a femme fatale duck, styled after famed spy Mata Hari. Their secret slogan is "Hitler stinks."

"Russian Rhapsody" came out in the same year, featuring Hitler plotting to destroy Moscow. He is thwarted by a rag-tag bunch of gremlins, apparently styled after Jack Warner and his close associates.

Bugs Bunny himself joined the propaganda drive in 1945's "Herr Meets Hare," poking fun at Germans for falling under the spell of fascism.

As mentioned, the Warner brothers were not alone in their animated war contributions. Disney, too, signed up – releasing its own anti-Nazi 'toon in 1941, "The Thrifty Pig." The film is based around the tale of the The Three Little Pigs, with the big bad wolf appearing as a Nazi.

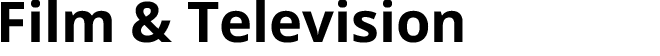

Disney came back in 1943 with Donald Duck in "Der Fuehrer's Face," which went on to win an Oscar for best short animated movie.

Following in Daffy's footsteps, Donald Duck also became "Commando Duck" in 1944, in which he went to fight the Japanese.

MGM joined the fray in 1942 with "Blitz Wolf," also a take-off of The Three Little Pigs, who this time face off against Adolf Wolf.

After Pearl Harbor, Paramount Studios brought its own star player, Popeye, into the propaganda effort, sending him off to fight against the Japanese in "You're a Sap, Mr. Jap," a film that by today's standards comes across as unabashedly racist.

Popeye followed up his success against the Japanese by joining the British in their fight against the Nazis, in 1943's "Spinach fer Britain."