Operation Entebbe as told by the commandos: Planning the mission

40 years after one the most famous commando operations in history, Sayeret Matkal's soldiers recount the events that culminated in the release of 106 hostages from an airport terminal in Uganda: The plan that fell through, late-night calls, and how such a large-scale operation was put together in only 48 hours. Part 1 of 5.

"Mission Impossible," was the Daily Mail's headline the day after the Entebbe Operation. "No country in the world would dare try such an operation, as it truly was a mission impossible," the British paper wrote. "But Israel dared—and won."

"One of the most shining examples of an operation conducted by any army," Yaacov Caroz assessed in the daily Yedioth Ahronoth, and the myth was born: That very day, the operation in Entebbe became one of the most well-known commando operations in history.

On Sunday, June 27, 1976, Air France's Flight 139 left from Ben Gurion Airport, made a stopover in Athens, and then took off towards its final destination, Paris, with 248 passengers on board. At around 12:35pm, four terrorists—two German and two Palestinian—hijacked the plane.

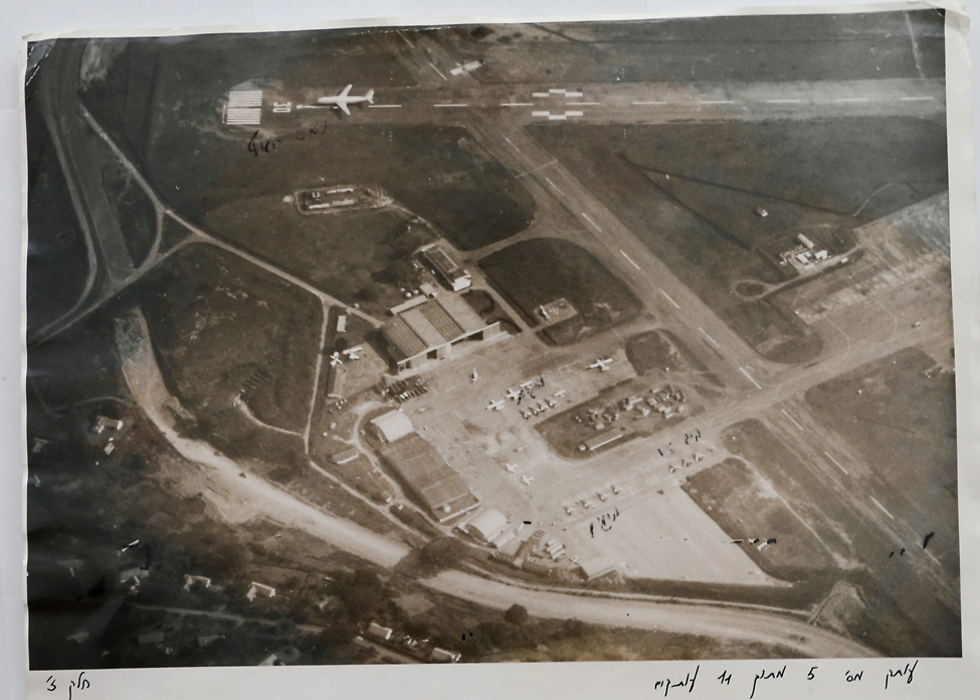

After a stopover in Libya, where additional terrorists came on board, the hijacked plane landed in Uganda. Its passengers were led to the old terminal building in Entebbe, where they were guarded by both the kidnappers and Ugandan army soldiers. On the third day, June 29, the terrorists decided to separate the Israelis and Jews from the rest of the passengers and released the latter group.

Because of the great distance from Israel, the hostile area and the lack of time, a military rescue operation seemed like an unrealistic option, if not a pure fantasy. But on the night between July 3 and 4, 1976, four Israeli Hercules planes carrying IDF commandos landed in Entebbe. Their mission: Free the 106 Jewish and Israeli passengers, as well as the Air France crew. The task force included the elite Special Forces unit Sayeret Matkal, as well as Air Force pilots, Paratroopers and Golani infantrymen, Medical Corps personnel and a fueling team.

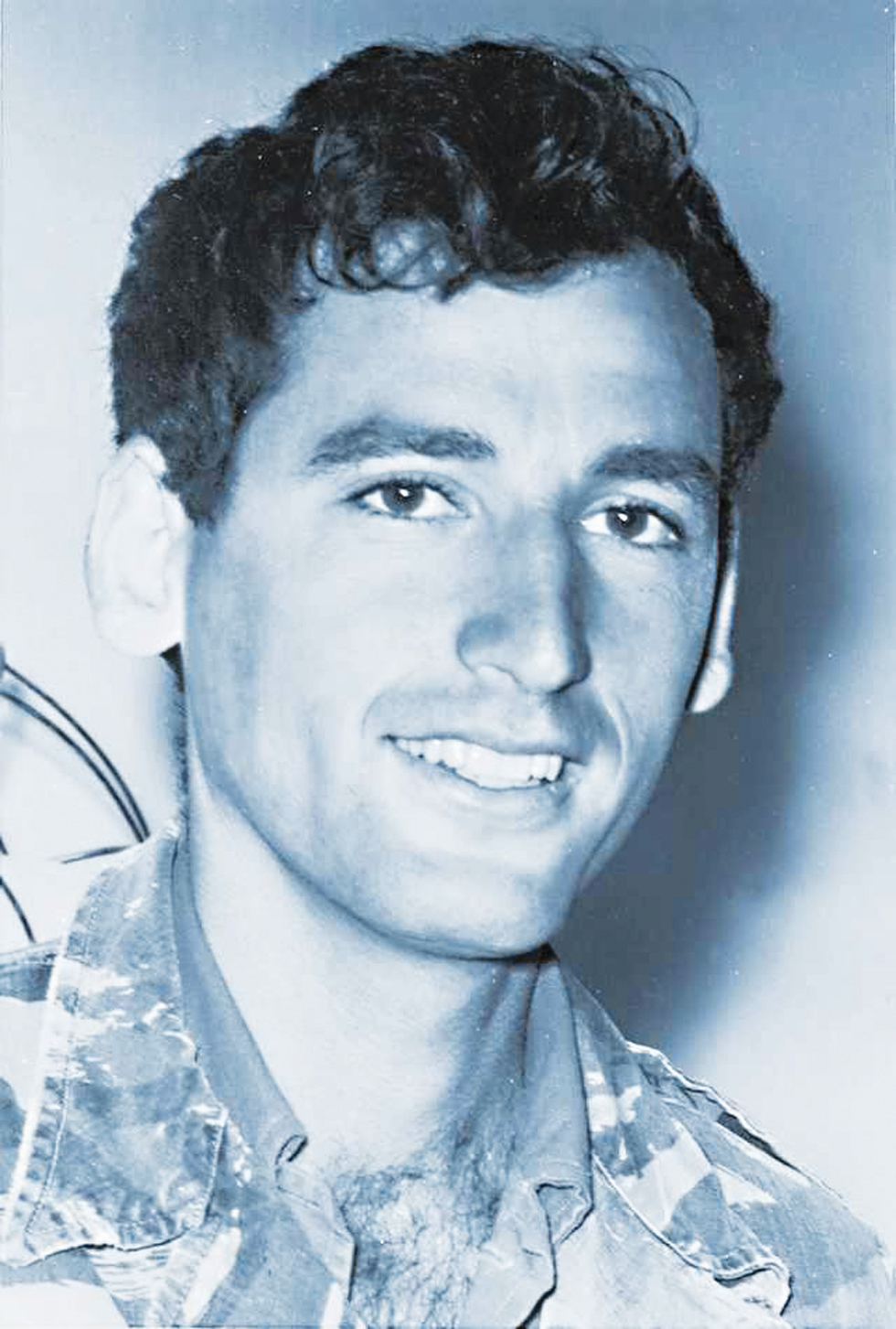

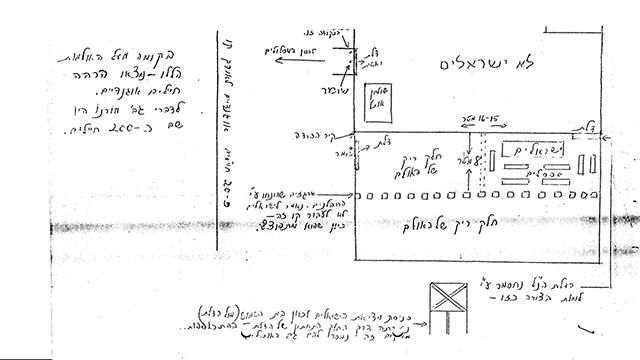

Sayeret Matkal was tasked with releasing the hostages. The force that would storm the terminal, led by Sayeret Matkal Commander Lt. Col. Yonatan "Yoni" Netanyahu, included 33 commandos: a fireteam led by Muki Betzer and another led by Amnon Peled, which stormed the area where the hostages were kept; a team led by Yiftach Reicher-Atir, which handled the customs area and the Ugandan soldiers' quarters on the second floor; a team led by Giora Zussman, which stormed the "small hall" that was used by the terrorists and where it was feared some of the hostages were kept; a team led by Danny Arditi, which handled the terminal's VIP area; and a team led by Rami Sherman, which was responsible for vehicles and cover fire.

The operation was seen as a glowing success, but at a terrible price: Commander Yoni Netanyahu was killed, three of the hostages also lost their lives, and paratrooper Surin Hershko was left paralyzed after suffering a spinal injury. One of the hostages, Dora Bloch, who was previously taken to hospital after choking on a fish bone, was murdered by Ugandan despot Idi Amin's soldiers.

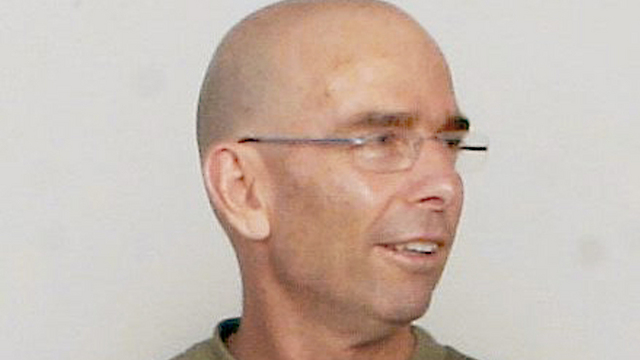

Three months ago, I invited a group of friends for a unique meeting at the Entebbe exhibition at the Rabin Center: former Mossad operative Avner Avraham, the curator of the exhibit, Akiva Laxer, one of the hostages, and Amir Ofer, one of the commandos, the first to storm into the terminal.

Ofer stressed the link between his own personal history—he is the son of Holocaust survivors—and the Entebbe Operation. As we were touring the exhibition, he recounted his experiences, telling all types of stories, with some being amusing anecdotes of what happened behind the scenes in the planning stages of the operation. For the first time, he brought his parents, who barely survived the horrors of World War II, and his daughter, to the exhibition. That moment that brought together the commando, his parents, the surviving hostage who owes Ofer his life, and Ofer's daughter, didn't leave a dry eye in the house.

While I was listening to Ofer, I was thinking what a shame it was that these stories remained in this small circle and weren't public knowledge. So I was very happy to learn a few weeks ago about a new initiative by some of the commandos to change that. In honor of the 40th anniversary of the operation, the Intelligence Heritage and Commemoration Center is releasing a book titled "Operation Yonatan in the First Person." The book is an anthology of first-hand testimonies of 35 Sayeret Matkal soldiers and officers who took part in the operation. The head of the book's steering committee is Danny Arditi; and the book was edited by Yiftach Reicher-Atir, Shlomi Reisman and Aviram Halevi.

When I read the commandos' testimonies from Entebbe, I felt that this was an important historical document, which sheds new light on that mythic operation and also on several controversies still surrounding it. After a series of meetings with the creators of the book, we agreed that, due to the importance of the topic, it's is vital that as many people as possible are exposed to the fascinating testimonies it presents. That is why we decided to publish selected excerpts from the book's testimonies this week, and, with their help, paint a picture of what history's most famous commando operation looked like.

Two different plans of action

Yoni Netanyahu received the news of the hijacking of the Air France plane while he was on his way to the Sinai Peninsula to prepare for an important Sayeret Matkal operation. Avi Weiss (Livneh), who was appointed Sayeret Matkal's intelligence officer just as Netanyahu took command of the unit, was with Netanyahu when the news came.

"While we were on our way south, we received a report about the hijacking of an Air France plane," Weiss recounts 40 years later. "The soldiers who remained at the unit's base were on alert in case the plane circled back and landed in Lod (at Ben-Gurion Airport). But as soon as the plane landed in Entebbe—about 4,000 kilometers from Israel—the high level of alert at the unit was lifted under the assumption that we weren't going to take part in this hostage situation.

“While we were on deployment in the Sinai, Muki Betzer (Netanyahu's deputy —ed.) sent reports to Yoni about the discussions at the different levels of the IDF’s high command examining different operational options to rescue the hostages. The reports we received in Sinai were laughable, and sometimes led us to scorn at the thought that the IDF could carry out an operation like this beyond the mountains of darkness (a place in Jewish tradition where the Ten Lost Tribes of Israel are believed to have been exiled by the Assyrian king Shalmaneser V —ed.)."

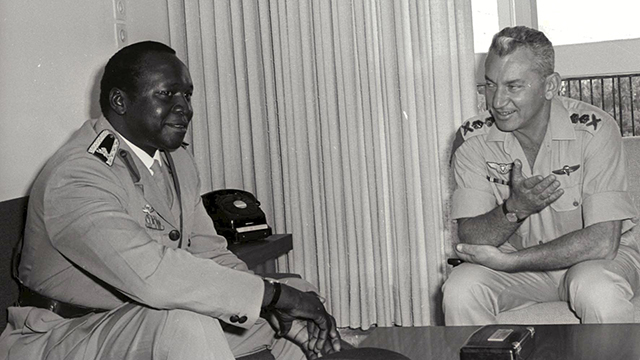

Muki Betzer, who would later go on to become the first commander of the elite Air Force commando unit Shaldag, knew Entebbe well. At an early stage of planning the operation, he met with Ehud Barak, who was at the time the assistant for operations to the director of Military Intelligence and one of the planners of the operation.

"When I walked into Ehud's office, there were already several officers from the different corps there," Betzer recounts. "'Well, Muki, what can you tell us about the Ugandan soldiers?' Ehud asked me.

"'I only trained them for four months,' I responded. 'Had I kept training them, they'd be better now.' Everyone laughed.

"'And yet?'

"'They're scared of their own shadow, and generally they're not very motivated. And, in this case, I really think they're not motivated to fight.' That's how the planning for Operation Entebbe began.

"As the representative of Sayeret Matkal, Ehud tasked me with preparing the plan to storm the old terminal building where the hostages were being held. The Solel Boneh construction company gave us the blueprints for the building, but we were still missing vital pieces of information. After the meeting, I called Yoni and told him about the establishment of the team. We agreed that if it seemed things started moving forward, I'd let him know and make sure he's flown in from the Sinai."

Weiss recounts, "On Thursday, July 1, early in the morning, we rushed in Yoni's car back from the Sinai to the unit's base, a six- or seven-hour drive. After getting things ready at the unit, I left with Yoni and other officers for Beit Hazanhan (a conference room in Ramat Gan —ed.), where we met with Dan Shomron (the head of the Infantry and Paratroopers Branch at the time and the commander of the rescue operation —RB, LBA). There, we met with Betzer.

“At that meeting, Dan Shomron presented us with the two main ideas under discussion: Parachute a military force into Lake Victoria, arrive at the beach, take over the terminal in Entebbe, free the hostages, and transport them by land in vehicles that would be captured during the takeover to Kenya; or arrive at Entebbe with a large military force in eight Hercules planes, take over the airport, rescue the hostages, and fly them back to Israel. At this point, at least to me, these ideas sounded borderline delusional."

Nevertheless, both plans were being discussed seriously. Michael Aharonson, a recently-released Sayeret Matkal commando, was at the time working as a military instructor in neighboring Kenya.

"Before the Friday of that week, Ehud Barak arrived in Kenya," Aharonson recounts. "I thought one of his objectives was to calm down the Kenyans. But he, on his part, didn't volunteer any information to us. At that point, we were informed that the plan currently being discussed to free the hostage was to parachute Shayetet 13 (a special ops Israeli Navy unit —ed.) commandos with rubber boats into Lake Victoria, have them make their way to the airport in Entebbe—which was located right on the lakeshore—raid the terminal, and release the hostages.

“While we were discussing the plan, we received a question from back in Israel: Are there crocodiles on the lakeshore? I was told two Shayetet 13 commandos were making their way to Nairobi. I rented the only car I could find, a tiny Fiat 127, and went to the airport to pick up the two—one of them being Shayetet 13 deputy commander at the time, Hanina Amishav. We drove for hours all the way to the lakeshore. We got our answer as soon as we arrived there. There were crocodiles, and they were massive Nile crocodiles who were lying in almost endless parallel rows along the shore, as far as the eye could see."

Even before that discovery, the raid plan with the Hercules planes began gaining momentum. The Sayeret Matkal commandos were called to the unit.

"We were called to return to the unit in a phone call at midnight, on the night between Thursday and Friday," remembers Amir Ofer, at the time a first sergeant in the Amnon Team. "I was already asleep when the phone rang. My parents answered, knocked on the door and told me, 'It's for you.'

"On the line was Yael, the secretary: 'Be here by 8am.' I immediately made the connection that this had to do with the hijacking.

"I asked her, 'Are we going far?' and she said, 'You're going very far.' My mom was in the room at the time, heard me ask 'going far?' and put two and two together. Then she became pale. Her look said it all; I told her not to dare breathe a word of this."

Preparing for the operation

Additional forces joined the Sayeret commandos’ preparations. "Air Force personnel disassembled the inside of the plane and put it back together so it could carry the troops and the fuel. This is something that just getting operational approval for usually takes half a year, and they did it in three days," explains Amnon Peled, then a captain in the unit and the commander of the Amnon Team.

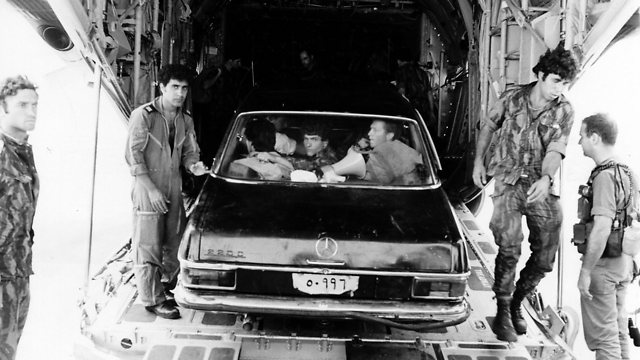

"During our preparations—which included military simulation exercises, getting on the vehicles, drilling skirmishes, getting off the vehicles—a Mercedes showed up out of nowhere, and we got the idea to dress up as Idi Amin's soldiers, Ugandans in leopard uniform and Kalashnikovs. We got all the equipment we needed from logistics, including white hats, so we could tell who was us and who was them. Anyone who served in the army knows that when you go to logistics, the quartermaster clerk always says, 'I don't have this' or 'Today we're closed.' But this time, the door was open, and the quartermaster clerks asked us what we wanted and what else they could give us. It was surprising.

“Our simulation exercise with the planes was scheduled for 7pm, and IDF Chief of Staff Motta Gur came to personally supervise us."

MK Omer Bar-Lev, who went on to become the commander of Sayeret Matkal, commanded an armored car and a fire team operating around the terminal during the operation.

"The plan took shape during the day; one briefing followed the next. I was really shaken after a briefing in the afternoon, because the plan sounded like a Swiss cheese, filled with giant holes. I had quite a few notes during the briefing, some were really fundamental. For example, Yiftach Reicher and his team were instructed not to clear the first floor of the old terminal with gunfire during their search of it, and only to open fire if fired upon. Another example was the instruction for every plane that had its team return to it to take off without waiting for the other planes. I got up again during the briefing and said it was a flawed decision. Karnaf 3 (the Hercules plane —RB, LBA) must wait on the runway for 4, and only when Karnaf 4 is ready for takeoff, they should take off together. Otherwise, a situation could take place in which Karnaf 4 is left alone, the last one, taking Ugandan fire and losing the ability to take off, resulting in all of the troops aboard it staying in Uganda.

"On Friday night, after the simulation exercise, I arrived at the commander's office and entered the unit's deputy commander's room. We were sitting there, a few officers around the table. A really bad feeling prevailed in the room. We felt that the plan wasn't as airtight as we were accustomed to; the simulation exercise was a joke in our eyes, and we felt very uneasy, to put it mildly, about the fact that the IDF chief and the higher ranks were impressed by these exercises. I felt that the officers around the table were pressuring me to update my father (Haim Bar-Lev, the IDF's eighth chief of staff and the trade and industry minister at the time—RB, LBA).

"My father, because of his role as a member of the government, knew, of course, that I was part of the force that was going to Entebbe. At a later point I decided it was my duty to update him on this. In my five years of service in the unit, never had I had any conversation even remotely like the one I was planning to have with my father, quite the opposite. And so, I found myself that Friday night driving my D200 truck to Neve Magen (in Ramat HaSharon) to talk to my father.

“After crossing a junction, the hood of the car suddenly opened while I was driving. It flew up and blocked the entire windshield. I immediately stopped, got out of the car, and closed the hood. I went back into the car, started it, turned it around and drove back to the unit. I've wondered more than once since what would've happened if the hood hadn't opened."

Meanwhile, preparations for the operation continued with great urgency. Shlomi Reisman, then a commando and first sergeant in the Amnon Team, remembers, "We knew what we had to do. So we dedicated the little time we had left to drilling the more specific, technical aspects of the operation. None of us had ever practiced hitching two Land Rovers and a Mercedes inside a Hercules plane, for example, and Giora Zussman kept timing us, over and over again, relentlessly. Special attention was given to drilling quickly unloading the vehicles after landing; everything to shorten to a minimum the time we needed from the moment the Hercules's back ramp opened to the moment we arrived at the old terminal where the hostages were kept. Someone went to a bookstore, and using a map from a textbook atlas I learned where Uganda was and we planned how we were going to hijack vehicles and flee to the neighboring Kenya (if the operation fails —RB)."

Weiss recounts, "One of the main points of weakness of this operation was the lack of an ongoing and up-to-date contact with the target. I was feeling uneasy, to put it lightly, because the information we had on the terminal was mostly based on old plans, and our knowledge of the activity at the old terminal and around it was only partial.

"On Friday night, after a tense wait, a detailed and updated intelligence report came from Amiram Levin, who flew to Paris to question the foreign hostages who were released. This report contained information that was accurate as of Thursday morning. It was clear that the chances of getting any additional information before Saturday night—the planned zero hour—were very slim. This meant we were going on the operation with a three-day gap, that we didn't have a chance of obtaining more up-to-date information regarding the hijackers and the activity at the terminal in Entebbe. So we had no choice but to hope there would be no changes, and at the same time expect surprises."

Meanwhile, and even before the decision was made on the operation's personnel, there were internal struggles among the Sayeret Matkal commandos, who all wanted to take part in the special mission. "Reservists, who heard the rumors about the operation, began making calls to Yoni and other officials in the unit, asking to be included in the force going on the operation," Weiss says.

"Out of my dozens of soldiers, one could not go," remembers Danny Arditi, who would later go on to become the head of the National Security Council but at the time was still a young captain and the commander of the Arditi Team.

"When Yoni told me I had to give up one of my soldiers, I was very angry and started arguing. I really fought for that soldier, to the point of almost walking away. I told Yoni, 'If he's not participating, then I'm not participating!' and left his office furious. I went down the stairs to the courtyard and came across Muki who explained to me there was no other choice. In the end, that soldier did not participate. I think he's mad at me to this very day."

Part 2 of this story recounts the journey to Entebbe and the tense drive up to the terminal.

Dr. Ronen Bergman is Yedioth Ahronoth's chief military and intelligence correspondent. Follow him on Twitter @ronenbergman

Lior Ben-Ami is the head of Yedioth Ahronoth's investigative team. Contact him at [email protected]