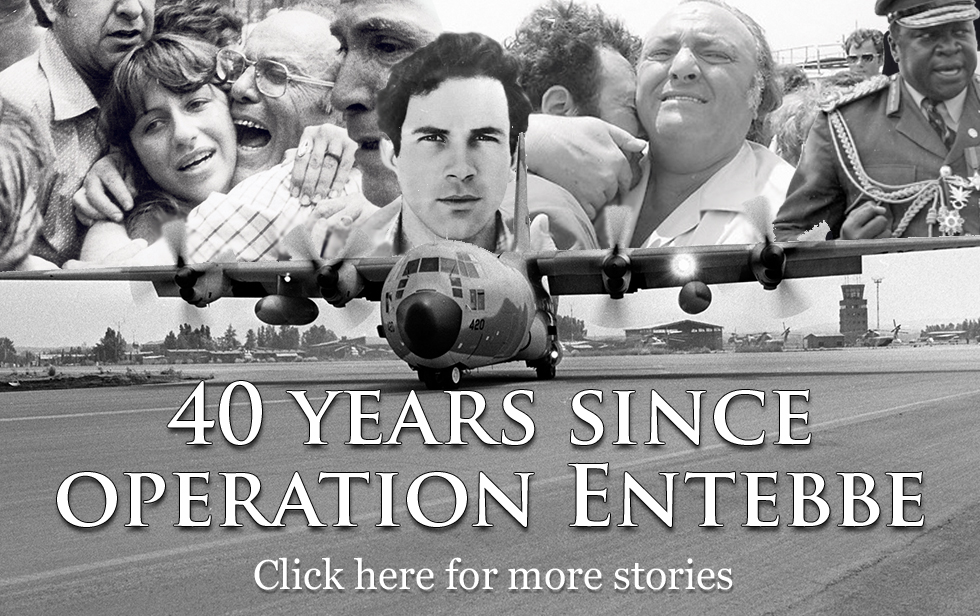

Air France pilot recounts: 'We were not going to leave the Jewish passengers in Entebbe'

40 years ago, Captain Michel Bacos flew the Air France plane that was hijacked to Entebbe, but when the hijackers offered to free him, he insisted on staying with his Israeli and Jewish passengers to the end. Now, at age 92, Bacos tells his incredible story to Yedioth Ahronoth.

Today, Michel Bacos, the captain of the Air France plane that was hijacked to Entebbe, is 92 years old, but the story of the hijacking is etched into his memory, and he can recount it as if it happened just a few months —and not 40 years—ago. Ahead of our interview at his apartment—which overlooks the beautiful Bay of Angels in Nice in the south of France—his wife asked I have the questions I was planning to ask him in advance, to allow him time to recollect his memories. But despite the fact he had prepared written answers ahead of time and brought documents he could rely on should he forgets any detail, the events of that incident are reignited in his memory. He abandoned his papers and got lost in his own story.

Bacos, an experienced Air France pilot, was in charge of Flight 139 that left Ben-Gurion Airport for Paris on June 27, 1976, with a stopover in Athens. When the plane landed in the Greek capital, four terrorists boarded the flight—two Palestinians from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and two Germans—carrying weapons and explosives in their bags.

"The hijacking was carried out four minutes after the plane took off from Athens towards Paris," Bacos remembers.

"My co-pilot had his hands raised and we put the plane on autopilot. We told him (Böse) a few times: 'Please, don’t shoot.' Then he calmed down and ordered the technician to return to his place and my co-pilot to sit with the passengers. I asked him why, and he responded: 'Because there are too many people here. I am alone and you are three,' even though he was armed and we weren't.

“The co-pilot joined the passengers until we arrived in Benghazi and then I brought him back into the cockpit. Böse sat behind me with his gun pointed at my head. Every time I tried to look in a different direction, he pressed the barrel of his gun against my neck.

"When we landed in Benghazi, I stayed in the cockpit. I spoke with the hijacker, Böse. I demanded that he allow my technician to get off the plane onto the runway to supervise refueling. The plane was modern and the Libyan ground technicians did not know how to refuel it. Böse agreed.

“On our way into Benghazi, Böse prepared a speech in (Muammar) Gaddafi’s honor and read it on the PA system. A few minutes after his speech, we received confirmation to land in Benghazi. Everything was organized ahead of time. Böse told me in English to make a soft landing because they booby-trapped the airplane doors with explosives to prevent passengers from fleeing. Because I didn’t want to die, I landed as he requested."

On the plane's way out of Libya, "the control towers (in Benghazi) hailed us, but we couldn’t respond. They realized we had been hijacked after they saw us on the radar changing our route and redirecting southward."

“After landing in Entebbe, the hijackers spoke between themselves like crazy people. The passengers and the crew kept quiet. Only after three or four hours did people start talking. No one knew what was going to happen," Bacos continues.

“All of us were initially put in the same hall. They brought us mattresses and we slept on the floor. The hijackers had a separate area of their own. The Palestinians told the Germans what to tell the passengers. They were in control of the situation and the Germans merely helped them. Their mission was to carry out the hijacking at all costs. Böse was the only person who had the capabilities to carry out such a (task) because he had experience flying planes."

'We'll kill you all'

To this very day, Bacos is considered by many to be one of the heroes of the Entebbe hijacking because of his refusal to leave his Israeli and Jewish passengers behind.

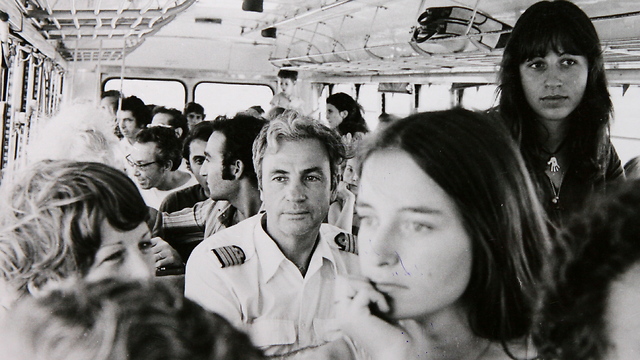

"At a certain point, the hijackers took our passports and IDs, read the names, and those who had Jewish names were separated from the others and put in a nearby hall. They (the hijackers) said we were not allowed to go there. I told the Palestinians and the Germans: 'I'm responsible for all of the passengers and demand to be able to see all of them—be they Israeli or not—at any given moment.' I insisted, and the Germans agreed. I was able to go from one hall to the other without receiving permission, every time. It lasted until the non-Jewish passengers were released. The Germans told me on Tuesday that we were going to be released. I gathered my crew and told them there was no way we were going to leave—we were staying with the passengers to the end. The crew members immediately agreed. I told Böse that none of us was going to leave Entebbe as long as there are any passengers left there. The crew refused to leave, because this was a matter of conscience, professionalism, and morality. As a former officer in the Free French Forces, I couldn't imagine leaving behind not even a single passenger."

The flight crew members, with Bacos among them, remained with the Jewish hostages. "We were not allowed to leave the hall," Bacos remembers. "No one could escape or leave. At any moment we could've been executed. We had to remain calm, otherwise the Palestinians were capable of killing us. We all knew it. We had no contact to the outside world: No phones or radios. No one knew what was going on. Idi Amin (the Ugandan despot —ed.) came and told us nonsense. I heard what he told the passengers, but I haven't spoken to him personally. I didn't have anything to say to him. I knew he was crazy. Passengers asked him to help us, and he insisted to be called all of the titles he gave himself. Every time he came to see us, he said: 'I'm your friend, but if your countries don't accept the ultimatum of the Palestinians, I'll give the order to execute you.'"

The IDF raid of the Entebbe terminal began at 11pm on Saturday night, July 3. Bacos remembers how the Israeli hostages were confident their country would not forsake them.

"I thought France would try to save us. There were French forces stationed in Africa, closer than Israel, but either way I knew someone would come rescue us. In the middle of the night we heard gunfire. Everyone dropped to the ground and laid flat on the floor, on the mattresses. We heard gunfire from all directions. During the week of the hijacking, I was talking to the flight technician when Böse approached us. The hijackers were prepared for the possibility someone would try to mount a rescue operation. He told us, 'If any kind of commandos arrive, it doesn't matter which country they're from, we'll hear them landing and then we'll come and kill you all.'

"When the rescue operation began, Böse came into the passengers' hall, stood next to the technician who was lying on the floor, and said: 'Stay down, don't move.' He took his machine gun, broke the windows and fired out. He couldn't see anything. The IDF soldiers identified the source of the gunfire and killed him and the German woman hijacker who was with him. But Böse didn't shoot any of the passengers.

"One of the Palestinians came into the passengers hall. They too were instructed to kill the hostages. He saw an Israeli passenger (Ida Borochovitch —ed.) and shot her to death at close range. The IDF soldiers identified him and killed him. There were two young passengers (Jean Jacques Maimoni and Pasko Cohen —ed.) who started running of joy and shouting 'Israel came to rescue us.' The Israeli troops thought they were terrorists and shot them to death.

"The shooting lasted for a long time. After about 30 minutes, the IDF soldiers killed all of the terrorists and about 20 Ugandan soldiers. The IDF had the airport's buildings surrounded, they had to clear the entire area. When they were done clearing the area, we were told to come out. 'We're taking you to Israel. Leave your luggage behind, its too heavy,' we were told. And so, we boarded the Hercules plane—some in nightgowns, some without shoes on. The soldiers brought the body of (Sayeret Matkal commander) Yonatan Netanyahu, who was killed by a Ugandan soldier stationed at an abandoned guard tower. We knew (the guard) was there, but we couldn't have alerted (the soldiers to that). We flew to Nairobi to refuel and leave the wounded IDF soldiers there. The Kenyans wanted to treat them, as Israel refused to sell fighter jets to Idi Amin, who wanted to attack Kenya—and the Kenyans have not forgotten that."

No longer afraid

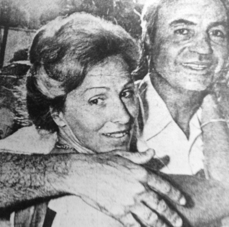

Bacos has been to many historical junctures in his life. He grew up in Egypt, where his father worked at the Suez Canal. When he was 17, Bacos snuck into the ranks of the Free France Forces, led by General Charles de Gaulle, which fought against the Nazi occupation during World War II. In the 1960s, he was in charge of the flights connecting the isolated West Berlin with the rest of Western Germany. That was how he met his wife, Rosemary, who was a German flight attendant at the time.

Rosemary is reluctant to talk much about what she went through in that stressful week in the summer of 1976.

"One of the Air France pilots was the only one who kept in contact with me, and he told me not to listen to the reports in the media. He was right. The reports gave a lot of false information. Those days were horrible. I only managed to fall asleep with the help of sleeping pills. On the night of the operation, the pilot, who knew I was asleep, waited until 6am and then called to tell me about the rescue mission. He said my husband and the others were not out of the woods yet, but that the hijacking situation had ended. It was a great relief."

I ask Bacos how long did it take him to get back to work after returning home. "About two weeks of rest," he says. "I demanded that my first flight would be to Israel, to see if I were still afraid. That flight went without a hitch and I was very glad to return to Israel."

Have you kept in touch with any of the passengers or the commandos?

"I'm still in touch with some of the passengers who live in Israel and with the soldier Surin Hershko, who was seriously wounded in his spine and left paralyzed. That's one brave man. The first time I returned to Israel after Entebbe, I went straight to the hospital to visit him. He couldn't move. I thought he wouldn't like to see me, but I was wrong. I brought my wife and three sons with me. Twenty years later, he asked the IDF to take him to Entebbe so he could forgive the Ugandan soldier who broke his spine. Hershko is a good friend of the family. There he is," Bacos points to a photo of him and Hershko, propped up on a small table not far from a trophy of appreciation given to him by the American Jewish Committee a few days prior. On a nearby shelf there are medals of service and bravery, and coins commemorating the Entebbe Operation.

"Another good friend of mine was the commander of the Hercules plane that brought us to Israel, Amnon HaLivni. He saw me on the plane before takeoff, sitting on the floor next to the covered body of Yoni Netanyahu. He told me, 'Your place is not here, but in the cockpit.' It was a lot more comfortable. We became good friends, and his death really affected me. I was at his funeral. I lost a close friend.

"I saw (Prime Minister) Benjamin Netanyahu once at an event we were invited to in Paris. I said a few words about Yoni Netanyahu's sacrifice, and later he came up to me and shook my hand."