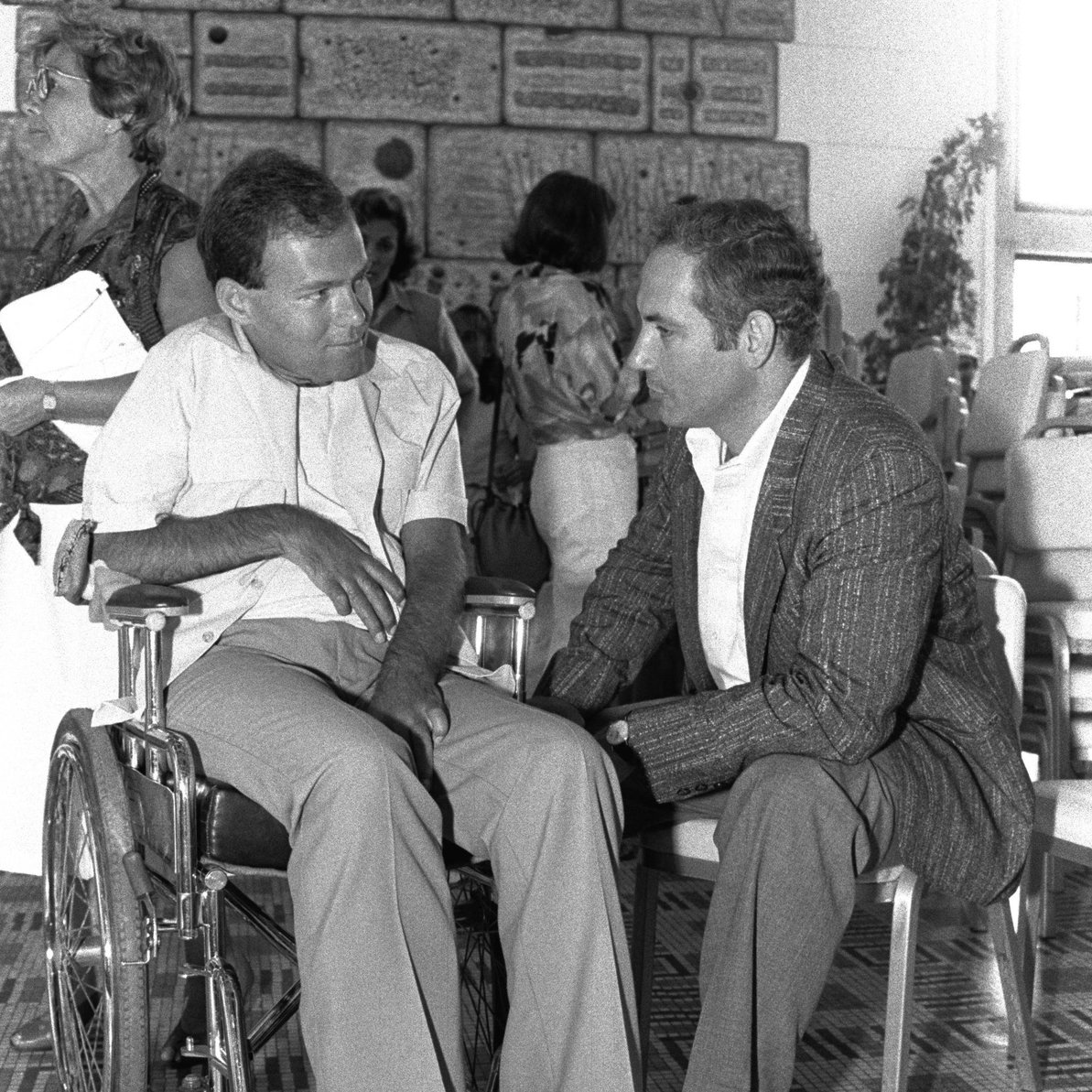

Entebbe's seriously wounded soldier meets with doctor who saved his life

For 40 years now that Prof. Joel Sayfan has been keeping a note stained with the blood of Surin Hershko, who became paralyzed from the neck down after suffering a bullet wound to his spine during Operation Entebbe. To this day, they haven't spoken to each other about what happened in Uganda that night.

At the beginning of their meeting, Professor Joel Sayfan takes out a note from an old photo album and shows it to Surin Hershko, a soldier who was seriously wounded during the Entebbe Operation. The 40-year-old note, which includes the schedule for the operation, is stained with Surin's blood.

A single bullet was fired by a terrorist at Paratrooper Surin Hershko. It entered his body through the right side of his upper lip without even leaving so much as a scar. But the bullet kept moving in a destructive path, breaking Hershko's teeth, and moving forward still until hitting his spine. Surin, who was only 21 years old, was left paralyzed from the neck down.

Joel Sayfan, 71, was at the time the Paratroopers Brigade's doctor. He was the first to get to Surin only a few seconds after he was wounded. The schedule, which was inside his right breast pocket, was soaked with blood when Sayfan leaned over Hershko to treat him, protecting him from further harm with his body. The doctor saved the piece of paper as "an evidence of a constitutive event."

"This is yours. The original note, you can do a DNA test on it," he told Surin, presenting him with the paper with its faded blood stains. "After returning home and taking off my uniform, I unbuttoned the shirt and pulled out the note, which was soaked with blood. I've treated wounded in the field, and in battles, and at nighttime—both before and after Entebbe—but it never became this personal. The sixty-some minutes, our entire stay on the ground in Entebbe, the entire operation, was spent treating Surin. Everything around it—the planning, the arrival, the return—it was all just background noise. The essence of this operation, for me, is Surin. It's hard to describe it in words. This is a real bond between two people who met under certain circumstances—in an event that was perhaps the most important in their lives. There is a true bond between us, a bond of blood."

Surin, who turned 60 last year, was emotional by the meeting. Forty years have passed since a bullet cut through his body and split his life into before and after Operation Entebbe.

"He's the one who saved my life," Surin says of Sayfan. "Without the IV, the bandaging and the morphine—I would not have survived. Joel also stayed with me when we left Uganda. I was lying on my back, looking up, unable to move or talk. All I could see was his face over me. It's an image that has remained with me my entire life."

Surin's speech is fluent. He hardly ever raises his voice, as that puts a strain on him, the result of his injury.

We met in Surin's home in Tel Aviv's Afeka neighborhood, not far from Beit HaLohem, a social center for the IDF's disabled veterans, where they receive rehabilitation services. His home is private, but very modest, an indication of its owner's character.

Prof. Sayfan and Surin have not kept in touch over the 40 years that have passed since Operation Entebbe. They rarely saw each other, meeting only at ceremonies and official state events.

"We never really got to talk. This is actually our first conversation," the professor says. The two haven't spoken to each other about what happened in Entebbe, either.

Watch the meeting between the two (in Hebrew)

"I remember the injury," Surin says, as Prof. Sayfan listens to him with rapt attention. "I fell forward, on my face. I tried to get up but I couldn't. I tried to call for help but because the injury was through my mouth, I couldn't speak. I saw a lot of blood in front of me, on the floor."

Sayfan recounts, "I got to Surin perhaps ten seconds after he was injured. I quickly turned him over. There was blood, a lot of blood. I instantly identified a bullet entry wound. I groped around, but couldn't find an exit wound and realized the bullet was stuck in his spine. I raised his hand, and it dropped. I saw he couldn't move anything. I asked him, 'Can you talk?' He indicated with his eyes 'No, I can't.' So I said 'Let's begin. I'll ask you all sorts of questions. If the answer is yes, you'll blink once. If it's no, you'll blink twice.'"

"I remember your instructions," Surin says. "'Blink. Once for yes, twice for no.' And then questions, a lot of them. 'Are you cold? Are you hot? Do you recognize me?' I remember it was very important to you that I remained conscious. It was important to me, too. I was afraid that if I fell asleep, I wouldn't wake up again."

Sayfan explains, "Had he fallen asleep, how could I have known if he was breathing okay? I could've missed the moment he stopped breathing. So we talked all the time. I talked his ear off. 'How do you feel? Are you in pain? We'll be there soon.' I kept looking at you, to see if you were breathing."

What could've happened

"The worst thing that could happen, happened to Surin," Prof. Sayfan says, and quickly adds: "Almost.""This 'almost' is very significant," he explains. "Because I think Surin did a lot in his life. He paid the ultimate price, his sacrifice was enormous, his life was ruined. It's one step above losing one's life."

"I prefer the definition 'seriously wounded,'" Surin comments quietly. "I paid a price, a very serious one. My disability is very grave. The limitations I suffer from are many. These aren't things I can ignore."

Do you sometimes think of what could have happened if you hadn't been wounded?

"No, it won't do any good. It happened. I don't think I made such a bad decision at the time, to participate in this operation. Being part of such an operation is a badge of honor for me. It is very possible that the circumstances of my injury helped me come to terms with it more easily. It's hard for me to say how I would have reacted if I had been injured in some unnecessary accident instead.

"Of course I wish I hadn't been wounded, that's completely natural. But at no point did I wonder why me, or why did it happen to me, or what that soldier, the 21 year old, would have done had he known in advance he was going to get hurt. I consider the facts, the information, all of the knowledge I had at that time, and I know I couldn't have made a different decision. Not because of the cost. Because you can't just walk up to a soldier and tell him 'You're going to get wounded.' There was no operation in which the soldiers were told 'Guys, you're going on this operation, and the chances are that half of you won't come back home.'"

Prof. Sayfan interjects, "I understand what Surin is saying. He, in hindsight, is both sorry and not sorry. He's obviously sorry he was hurt, but if he had to go back to the moment before the operation, when he was asked to go, I'm sure he would've done it again. If I were in his place and I was asked, even today—I'd go again."

From Romania to the Paratroopers

Surin Hershko was born in Romania. He was named after his grandmother, Sarah. He made aliyah to Israel at the age of 12, moving to the Ramat Eliyahu neighborhood in Tel Aviv with his parents and older brother. Half a year later, his father died of cancer. His mother remarried and the family moved to Nahariya, where Surin grew up. He can't remember having a particularly hard time to fit in, quite the contrary: He learned Hebrew pretty quickly.

What made you want to join the Paratroopers?

"Perhaps it was part of my desire to fit in, to be a Sabra, to be more Israeli. The red beret, the shoes—it makes an impression. I'm sure I imagined myself coming home with my red army boots and having people look at me with respect."

He only has two photos of himself from before his injury. One with his friends from the Paratroopers company and the other on his own, in black and white. A handsome young man.

He enlisted to the Paratroopers' 890th Battalion two weeks before the 1973 Yom Kippur War. At first, he and his fellow recruits sat idle at the brigade's training base, but later they went through an accelerated basic training and sent to fight in Egypt. Then, they were sent to the Syrian enclave in the Golan Heights.

Sayfan is ten years older. He made aliyah from Poland in 1957. He knew he wanted to be a doctor from the age of five, like his parents and grandparents. He wanted to become a soldier-student and got accepted to medical school at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, but then it turned out he had failed one of his matriculation exams and therefore did not get his high school diploma. Instead, he joined the Paratroopers, fell in love with the brigade and even became an office. The IDF then sponsored his medical studies, and so began a long service in the military that lasted almost a quarter of a century. Throughout his career in the IDF, Sayfan served in both military roles and in positions in the public health system.

On June 27, 1976, an Air France airplane was hijacked by terrorists who flew it to Entebbe in Uganda. A week later, on July 4, the IDF mounted an operation to free the 106 hostages. During the rescue mission, Sayeret Matkal commander Lt.-Col. Yonatan Netanyahu and three hostages were killed.

Surin was on his way out of the army. He was planning to start studying economics at the Hebrew University in October of that year. But the operation changed everything.

"I was a radio operator in the Golan Heights. I had already returned my equipment to logistics. Nehemiah Tamari (then-commander of the 890th Battalion —ed.) called and asked me to tell Giora Eiland, our company commander, to organize a group of soldiers. 'A bus will come and take you to a base in central Israel,' Tamari said. It was on Thursday night. We said 'Okay, this must be a retaliatory operation in Lebanon.' We couldn't imagine we'd be sent to Entebbe."

Hershko was among those selected to board that bus and participate in the operation. "The soldiers were hand-picked," he says. "That's why when I was wounded my first thoughts were of frustration. I knew the operation was very important and each soldier was hand-picked to be there. And there I was messing things up. They had to worry about me instead of everything else that was going on around us."

The brigade doctor, Joel Sayfan, also received a call that Thursday evening. He was asked to arrive at the base in Sirkin the next morning. He too, like Surin, thought this was another military operation in Lebanon. When they arrived at the Sirkin base, both of them realized what the operation was about.

"We saw vehicles being loaded onto Hercules planes, soldiers practicing getting on and off the plane. We didn't have to be told anything else, we understood," Surin said.

Sayfan remembers, "I was with the group of commanders, the officers. We started planning the operation. Until that point, there were informal plans of Sayeret Matkal's raid of the old terminal. But there were still loose ends to tie up with the Air Force, the other forces, the Paratroopers, the Golani Brigade. Usually, even the smallest of operations in Lebanon required months of planning and training. In this case, we started doing simulations on Friday night."

What were you feeling?

"I don't know if you could call it euphoria, but we felt optimistic, that it could really work," Surin says.

Sayfan recounts, "On Friday night, I ran home to take a shower. I remember standing in the bathtub and singing. I was pleased, it felt good."

A flying operating room

The planes took off on Saturday. During final preparations, Sayfan wrote the note that would later be stained by Surin's blood. In English, he wrote the name of a medicine he gave the soldiers before taking off—Travamin, anti-nausea pills that were supposed to serve as a sleep aid for six hours."I didn't take the pill," Surin says. "I was confident I would not vomit."

The rescue team left for Entebbe on four Air Force Hercules planes. Surin and Sayfan were on the first Hercules, a fact neither knew before their meeting 40 years later. They were sure they had been on different planes.

They both remember Sayeret Matkal Commander Yonatan "Yoni" Netanyahu, who was on the same plane. "I actually saw Yoni for the first time" on the plane, Sayfan says. "He went from one person to the other—everyone who were on the plane—and shook their hands. As if he was saying goodbye to them. Not that I had some premonition, but I did look at him in that moment. No one else was doing that (shake hands with the soldiers)."

Surin recounts, "I remember he was sitting on the hood of the Mercedes we brought with us on the Hercules. He was reading a pocket book in English. I found that charming, that he has this peace of mind to read a book at that moment."

The elite Sayeret Matkal unit, led by Yoni, were responsible for the raid of the old terminal, where the hostages were being kept. The Paratroopers force, led by brigade commander Matan Vilnai, was advancing on the new terminal to take over it. The Paratroopers ran there.

"It took us a few seconds, about half a minute, to get to the new terminal," Surin says. "We waited outside for a little bit, waiting to hear the first shots fired at the old terminal. It was only then that we went in."

"To tell you the truth," he confesses, "I was supposed to be with Giora Eiland's team, to go upstairs through the outside staircase, and go straight to the roof. I wasn't supposed to go into the terminal at any point.

"On the one hand, I was a good soldier, fairly obedient. But sometimes I had my moments in which I didn't follow the orders to the letter. I decided it was more interesting to go inside, into the terminal. I thought it would be boring up on the roof, as I figured it's likely nothing would happen up there.

"So I ran with Nechamia Tamari. We were competing to see who gets into the terminal first. I beat him there, and we went into the new terminal as a group. We started running into all of the rooms and halls. There was a staircase leading to the second floor so Nechamia sent us there. There were very few people there—local employees or passengers waiting for their flight—and we gathered them all and took them to the ground floor. They were pretty shocked, and they obeyed.

"It was at this point that I headed to the outside stairs to go up on the roof and rejoin my team, with whom I should've been. It was then that I was wounded."

Which means that if you had gone up to the roof when you were supposed to, you might not have been wounded.

"You never know. Giora and another soldier went up on the roof immediately, while we were running into the terminal. I'm aware of the fact I didn't follow orders. On the other hand, if we stayed on the roof and then at some point gone down, and the person who shot me heard us at that point—I don't know what he would have done.

"I'm avoiding blaming myself. I imagine that had we gone home with all of us safe and sound, I'd get told off. I'd get yelled at for not following orders."

The Ugandan despot Idi Amin's son has claimed that Surin's force was tasked with checking if his father was still at the airport offices during the raid of the Israeli forces.

"He was shot by one of my father's bodyguards," Jaffar Amin told Yedioth Ahronoth reporter Itamar Eichner.

The Ugandan dictator, his son said, believed Surin Hershko had been killed. It was only 30 years after the operation that Jaffar learned from a BBC team that he had survived and was paralyzed.

"He's the one person I really want to meet," said Jaffar, who has expressed desire to meet with the families of the victims of the Entebbe Operation and ask for their forgiveness for his father's actions.

Surin remembers seeing someone's silhouette. Two shots were fired at him, and one of those bullets hit him.

"We were at the command post and heard two gunshots coming from above," Sayfan remembers. "Matan (Vilnai) called out to me 'Sayfan, go upstairs, see what's going on.' I went upstairs and saw someone coming out of the door. I realized this was the shooter and raised my weapon to shoot him, but he disappeared. I didn't manage to. At this point I also saw Surin on the floor. All I wanted to know in that moment was whether he could breathe. I was afraid he was bleeding into his throat or that there was swelling in his throat, as that would put him in mortal danger."

He bandaged Surin's face, and then he administered IV fluids. "All of this while the bullets were whizzing all around us," he describes. "There was a sniper who was shooting (in our direction) from the old terminal's control tower."

He was asked to quickly evacuate Surin by carrying him on his back, but Sayfan refused and demanded that a gurney be brought. "I knew that if I carried him on my back, I could exacerbate the spinal injury," the doctor explains. "Matan told me, 'If you don't come now, the crocodiles from Lake Victoria would eat you alive here.' But I insisted, and eventually four soldiers came and we took him on board the plane. We were last."

"I remember being put on the gurney," Surin confirms.

"We put the gurney on the hood of one of the Land Rovers we brought with us," Sayfan continues. "The aircraft technician set up lighting by hanging up a flashlight because the plane was relatively dark and I needed light. I asked for another doctor to join me on the flight, in case we needed to operate to clear Surin's windpipe. The procedure is called tracheotomy, and it was performed on him later, back in Israel, but we had the instruments ready in case we needed to perform it on the plane."

On the plane, they learned that Yoni Netanyahu had been killed. "It was a kind of a shock, for all of us," Sayfan says. "I remember telling Surin. I should have spared him and not told him. This just goes to show how shocked I was. I was also looking for things to talk to him about. I kept babbling on and on, so I let that slip as well."

Surin and Sayfan parted ways in Kenya. Sayfan flew back home on the Hercules, while Hershko was brought to Israel on a Boeing plane and rushed—while he was unconscious and in critical condition—to the Tel HaShomer Medical Center, where he underwent an operation to remove the bullet.

"One of the doctors wanted to sell the bullet and use the money to buy a machine for the hospital," he says. "At the time, after the operation, it was valuable. I wanted to keep it as a memento. I regretted that decision later. After all, maybe that doctor could have bought medical machinery with it."

For 30 years, Surin could not remember where he had been keeping the bullet. It was only before his meeting with Sayfan that he searched and found it in his home.

The realization of the true extent of his injury, he says, was "gradual."

"The late Prof. Rafi Rozin, who was the head of the Rehabilitation Department at Tel HaShomer, sat down with me for many talks. He tried to provide me with the most accurate description of my situation: Not give me false hope, but also wait until the situation becomes clearer, as it takes a month or two until things settle and a full assessment can be done of the severity of the injury. During the first three weeks, he'd poke me with a pin every day, to see if I felt anything. I, too, woke up every morning and tried to see if there was any change. When there was no change, I'd say 'Okay, we'll try again tomorrow.'

"Sometimes, the doctors would identify some sort of movement in my hand, and try to work with that. But with time they realized it wasn't significant. I couldn't do anything with that movement, not even move the wheelchair's joystick. And slowly, we realized (the extent of the injury). I realized after two or three months just how serious my injury was. I realized this will probably be the situation I'd have to deal with. And slowly, I also stopped trying."

Was there a period of mourning?

"No. I'm a practical man. My injury was a spinal injury, not a head injury. There are endless disabilities. But at least I still had the right, the privilege—I'm not sure how to call it—to make my own decisions, by myself. So pretty quickly my decision was 'Okay, this is the situation, these are the disabilities, let's see what we can do so, despite these disabilities, I could lead as normal a life as possible.' Depression and self-pity weren't part of the alternative."

There was a massive dissonance between the great joy across the country over the release of the hostages and your own situation.

"Yes, that's an accurate description. I think it was while I was still in the ICU that someone brought a projector and a screen and I was showed all of the news I missed, all of the reports on TV following the Entebbe Operation, so I could see the entire event."

And...?

"And I watched it, and was okay with it. I was happy with those who were happy outside (the hospital), and was worried by my own troubles and problems inside my room."

Using a stick instead of hands

Shortly after he landed at Ben-Gurion Airport, Prof. Sayfan went to Tel HaShomer Medical Center to see the wounded soldier, who was still sedated and on respirator. Only then did he go home. Afterwards, he visited Surin once or twice more at the hospital, while his patient was in rehabilitation. They didn't have any meaningful conversations, these were just formal visits in which Prof. Sayfan received an update on Hershko's situation, no more.Surin was hospitalized in the Rehabilitation Department for a year. He mostly underwent physiotherapy treatments. He missed the school year, so he registered for the next one, again to study economics and this time at Tel Aviv University, but had to quit soon thereafter. The fact he had to sketch and draw a lot of graphs made school impossible for him. He ended up getting a bachelor's degree in Labor Studies, a combination of psychology and economics. He started doing a master's, but then he discovered computers, which at the time were still a nascent field, and today he is a programmer. He uses a stick in lieu of his hands—which he moves with his mouth—to type on the computer keyboard or to type a message on his cell phone, and even to move his wheelchair around.

"This stick, just a stick, is everything to me," he laughs. "Sometimes I even scratch my nose with it."

He also has a caretaker. Over the past seven years, it has been Eric, a Filipino worker who has just about turned into part of the family. Eric knows exactly when Surin needs a drink of water, or anything else for that matter. Their bond no longer requires words. On the weekends, when Eric is off work, there are two Israeli caretakers who take his place.

"You have no idea how envious I am of paraplegics (those paralyzed 'only' from the waist down —CKB)," Surin says. "I constantly need the help of another person, while a paraplegic can mostly manage on his own. This is an entirely different life. It's the kind of thing I have a hard time accepting, this dependency."

What's the hardest thing?

"That's a difficult question. When I meet with someone who went through a good or a bad experience, it doesn't matter which, I feel like the best way for me to express myself in such instances is to give them a hug, a pat or a handshake—and I can't do that. And I try to explain that with words, and fail. Because sometimes I just can't find the words. Sometimes, the words don't really exist. There are circumstances in which words are not enough to express what I want, and that frustrates me."

Back to Entebbe

Tzila and Benzion Netanyahu, the late Yoni Netanyahu's parents, came to visit Surin Hershko at the hospital before he even regained his ability to speak.

"They finished the Shiva (Jewish mourning period —ed.), went to the Mount Herzl cemetery, to Yoni's grave, and from there took a taxi and came to visit me," Surin says. "I was still connected to the respirator, but I was choked with emotion. I was crying. They were sitting in my room, next to my bed. I think they also came back and visited me during rehabilitation. And after that we kept in touch. My mom also kept in touch with them."

"Yes, for ceremonies on the anniversary. Not every year, because Mount Herzl is problematic as far as accessibility is concerned. I come to pay my respects. I think he was a worthy man, that he deserves the respect."

Sayfan adds, "I never went. I didn't know him before the operation, so didn't see a reason to go."

Surin also keeps in touch with Iddo Netanyahu, Yoni's brother. When the prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, was Israel's ambassador to the UN, he gave Surin a tour of the United Nations building (in New York). Today, though, they are no longer in touch. "But in ceremonies, he always comes to personally greet me," Surin notes.

After the operation, a serious rift emerged between Muki Betzer, who was Yoni Netanyahu's deputy and the commander of the raid force, and the Netanyahu family. The disagreement centered on Yoni and Betzer's place in the Entebbe Operation pantheon.

"I think Muki Betzer is right," Prof. Sayfan determines.

"I think there's nothing more pointless than this," Hershko says of the arguement. "I can't really get into the small details, because I wasn't exactly there. I was a junior soldier. But these are insigificant, small things. There is enough honor for everyone. And this is something we should not have argued about. It pains me."

Throughout the meeting, the two keep repeating that each, in his own way, has "moved on with his life." Sayfan returned to Israel after the operation, finished his time as the doctor of the Paratroopers Brigade, and went on to serve in a series of other positions in the army, including as the commander of the 669 Rescue Unit. After his release from the IDF in the rank of lieutenant colonel, he was made the head of the Surgical Department at HaEmek Medical Center in Afula. He retired four years ago, and today continues working in a private practice. At the time of the operation, he had already been married with two children and has had two more after.

Surin, in addition to working as a computers programmer, is also the chairman of LOTEM – Making Nature Accessible, an NGO that offers accessible hikes and educational nature activities around the country to children and adults with special needs. The NGO is the only thing during the interview that he spoke about with evident enthusiasm.

Surin keeps in close touch with friends from the Paratroopers, as well as with some of the hostages. One of them, who was a child when she was kidnapped, told me that "Surin is one of the most important people in my life."

"I know what you're expected to hear from me," he says when I tell him about that. "For me to say that I saved their lives. But I don't feel that way. It's too bombastic, too pretentious. That's not my style.

He is also close to his brother, Ilan Harel. Like his brother, Surin also planned to Hebraize his name after his release from the IDF, but then he was wounded, and decided to keep his original name.

Sadly, he never got to have his own family. "This wasn't my decision, life just happened that way. Am I sorry about it? Yes. Is that the biggest price I had to pay? I don't know. You can't compare. In everyday life, I'm more bothered by the fact I need another person's help for everything I do. Meanwhile I don't wake up every day—not even every once in a long while—and think 'Why don't I have a family?'"

He has lived longer with his disabilities than without them. "But in my dreams," he reveals, "I can still walk. Not always, it depends what the dream is about. But there are dreams in which I get up and walk and get on the bus. And then I can't move forward, I get stuck on the way. Something is stopping me from moving forward."

While Sayfan has never returned to Entebbe, Surin went there once, 20 years ago, and doesn't want to to go back. "I got my closure," he says.

He also no longer spends his time dreaming of a magic solution that would allow him to walk again. "In the year that followed the injury, I went to London as part of a delegation of disabled IDF veterans. I was a guest in the home of a family whose father was in a wheelchair. At the time, he was about the age I am today. He tried to cheer me up and said, 'You don't know what the future holds. Science is advancing, medicine is advancing. New things are being discovered. I won't get to enjoy that, but you're young. At your age, you never know.'

"This is exactly what I would say today to a young person who became paralyzed in some operation. I keep following to see if there are any new advancements, but I'm not counting on it too much. At least not for me."