The KGB's Middle East Files: An aliyah of agents

In 1992, Vasili Mitrokhin, a KGB archivist, defected to the West with a trove of top secret documents from the Soviet intelligence agency, which helped expose many Russian agents and assets in Israel and elsewhere. This series of articles explores these documents and brings to light the secrets they revealed. Part 5 of 5.

It was June 18, 1967, shortly after 5pm. The last of the Russian diplomatic personnel had left the embassy building in Ramat Gan and minutes later, the Shin Bet stormed in.

"The Russians took everything," says a Shin Bet operative who participated in that raid, "they even peeled off the thick steel plates that covered the inside walls of the embassy's secret floor and ripped out the cables of their internal communications system."

The Soviet decision to cut ties with Israel was a major blow to the KGB. The Russians sought to fix the damage caused to their intelligence infrastructure in Israel with Operation TN, which included sending five "illegals" on short trips to Israel to serve as handlers for the assets still on the ground. But the entire operation went down the drain the day the Shin Bet arrested operation commander Yuri Linov.

It didn't take long, however, for the Russians to find a new source of intelligence. Jewish emigration from the Soviet Union to Israel increased starting in 1971. Between the years 1971 to 1973, some 100,000 Jews received permission to go beyond the Iron Curtain, with many of them choosing to make aliyah to Israel. This was an opportunity the KGB could not miss.

"I remember that at the time I was the head of the Leningrad KGB, and just from my district 200 of the emigrants to Israel were our agents," says former KGB general Oleg Kalugin.

"Obviously they didn't all work for us. There were those who crossed the border and in that very same moment turned themselves in to the Shin Bet. But," he says smiling, "there were others."

"They really flooded us," a Shin Bet agent describes those years. "We divided them into three groups: those who turned themselves in to the Shin Bet; those who didn't turn themselves in, but the KGB never contacted them; and the third group—that I believe some of which have never been caught to this day—were active agents of the Soviet Union."

The Mitrokhin documents list some of the names of the Jewish spies who were recruited at the time. The KGB picked emigrants whose professions it believed would be sought after by Israeli authorities, with a clear preference for the IDF.

For example, an agent who emigrated from Belarus in 1972, codenamed "Louis" and "Ivanov," was an expert on diesel engines and employed by the IDF in a classified position.

Another agent, "Jimmy," whose real name is Samuel Machtai, was a civil engineer who was recruited back in 1967 in the Soviet Union to "track nationalist Jews or those developing a nationalistic Jewish identity," according to his file.

He immigrated to Israel with his family in 1972, and they settled in Tel Aviv's Yad Eliyahu neighborhood. After a few years and after having passed all of the security tests, he was appointed to a classified position in the Israel Aerospace Industries' Engineering Division that, at the time, was working on the planning of their top-of-the-line Lavi fighter jet.

According to the Mitrokhin documents, "Jimmy" provided the Russians with a lot of information on the project and on other secret matters.

In August 1982, the Machtais decided to return to the Soviet Union. Machtai explained to his handlers that his wife could not adjust to life in Israel, but the KGB suspected—unjustifiably—that "Jimmy" had become a double agent, and placed him under strict monitoring. Nevertheless, Machtai went on with his life and even registered several patents in construction.

In December 1990, he decided to try his luck again and returned to Israel. This raised the suspicion of the Shin Bet, and Machtai was arrested in February 1991. During his interrogation, he confessed to and was subsequently charged with espionage. He was sentenced to seven years in prison under a plea bargain.

"I regret my actions," he told the court. "After I'm released from prison, I want to keep living in Israel with my family."

The Russians also recruited "Ulan," who was sent to Israel through Vienna in 1971 and became a radio personality and writer in a Russian newspaper. He didn't last long here either and emigrated in 1973 to West Germany, where he found success as the CEO of an international company that organizes conferences and conventions, a good cover for the KGB's activities in the country.

The KGB was also able to implant in Israel a female agent codenamed "Nora," who was hired by a Jerusalem-based company providing technical translation services to the government and other large companies in the country. This, of course, gave the Russians access to some valuable information.

Gregory Londin, an engineer who immigrated to Israel in 1973, was also recruited during that time. He was a reservist working on the maintenance and upgrade of the engine for the Israeli-made advanced Merkava tank. Londin was arrested in 1988, sentenced to 13 years' imprisonment, and was released in October 1996.

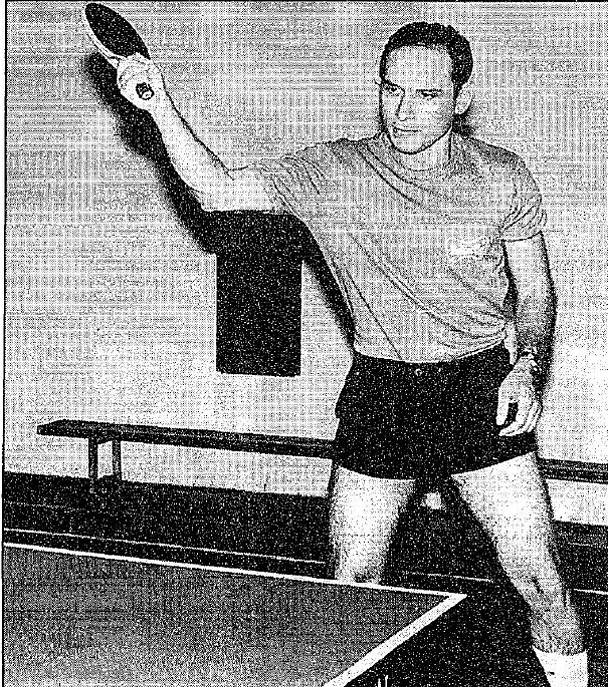

At the end of that year, thanks to information found in the Mitrokhin documents, the Shin Bet arrested Alexander Radelis, the former coach of Israel's national table tennis team.

Radelis provided his handlers with information he got during his IDF service using a radio and letters written in invisible ink. This information included details on the political and economic situation in Israel, the State of Israel's water supply, the tensions on the northern border, and the types of tanks and heavy equipments stationed in the different bases.

Radelis was tried, convicted and sentenced to four years in prison.

Another notable success in the KGB's recruiting of Jewish emigrants is an agent codenamed "Bejan." He was born in the mid-1950s in south-central Russia, studied engineering in the Soviet Union and was highly regarded in his field.

He was recruited as one of the KGB's "illegals"—the agency's elite unit of spies. After undergoing training, he immigrated to Israel and shortly thereafter enlisted in the IDF. He passed the Officer's Course and quickly climbed up the ranks until he was put in charge of one the IDF's main infrastructure projects. In this position, "Bejan" had access to many of the IDF's secrets, particularly regarding base locations, infrastructure, order of battle, and preparations for future wars.

After his retirement from the IDF, "Bejan" served in several other very senior civil service positions. He disappeared in 2004 and hasn't been seen or heard from since and could not be reached for comment. According to some reports, he returned to Russia.

'Sensitive matters'

The Shin Bet quickly caught onto the fact some of the immigrants coming to Israel could be Soviet agents and decided to conduct an initial security inquiry into every new arrival. Shortly thereafter, the agency caught two big fish.

During the first half of 1972, two KGB agents managed to infiltrate Israel—"Shomroni" and "Jupiter" (whose names are withheld by the Israeli Military Censorship). As part of the new procedure, the two were summoned for questioning by the Shin Bet. Something about their behavior raised suspicion; their answers were evasive and unsatisfying.

Later on, "Shomroni" also appeared to be seeking the company of public figures and opened a small business using funding the source of which was unclear.

The two were summoned for another questioning. They were invited to a hotel room in Tel Aviv's Ramat Aviv neighborhood—separately, of course—where Shin Bet investigator Yossi Ginosar was waiting for them.

This time, the interrogation was a lot less pleasant. "Jupiter," who had training both as a physical education expert and as a journalist, immediately confessed to having been recruited as a spy. "Shomroni" denied the accusation.

"Yossi didn't believe him for even a second, and tore him to pieces—not physically, of course," recounts one Shin Bet interrogator. "He realized this was a man who was very cunning and a skilled manipulator. But Yossi was no sucker, and a few hours later 'Shomroni' confessed to everything."

The Shin Bet interrogators were impressed with "Shomroni," describing him as a smart, clever man, "a genius manipulator."

"Shomroni" and "Jupiter" were then presented with a hard bargain: They could turn into double agents. Otherwise, they would face charges of espionage and treason. They agreed, and so they served Israel's interests for many years.

"Shomroni" soon became one of the top Russian agents in Israel. He provided the KGB with a lot of important information, which came, in part—or so the Russians thought—from inside sources. That information was actually a combination of true but harmless information and fabricated information.

The Shin Bet also helped "Shomroni" to establish his career in the country and instructed different government officials to aid him. This made him a very influential person in Israel as well.

"Shomroni" received his orders from the KGB while abroad. He would go on business trips, where he found an excuse to disappear for a few hours so he could meet with his KGB handlers.

Years later, "Shomroni" and "Jupiter" found themselves at the center of what is regarded as one of the most destructive spy scandals in Israel's history.

At the time, the Russians were trying to reestablish contact Dr. Marcus Klingberg—their top spy at the Israel Institute for Biological Research (IIBR) in Ness Ziona—unsuccessfully. The IIRB is a top secret facility where Israel is reportedly developing its most lethal biological weapon, as well as silent assassination measures used on occasion by the Mossad.

Klingberg, who cut his ties with the KGB in 1977 for fear he would get caught, thought that if he ignored the attempts to contact him, Moscow would simply forget about him. But the KGB was not willing to simply give up on such an asset and kept trying to contact him through different channels.

Eventually, in late 1981, the Soviets sent two of their agents to seek out Klingberg—"Shomroni" and "Jupiter." The double agents informed the Shin Bet about this, and the agency placed surveillance on Klingberg and collected information on his activities. Klingberg was later caught and sentenced to 20 years in prison.

"Shomroni" remained a double agent for the Shin Bet until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. After that, he continued thriving in business and found his way to the centers of power in Israel.

The Russians made great efforts to bring about Klingberg's release, including proposing a prisoner swap that included Jonathan Pollard and Ron Arad in return for their spy. These efforts were led by a KGB officer who was, at the time, a rising star in the agency—one Vladimir Putin.

"Unlike other spies who were caught in Israel, Klingberg was to us a senior official, and it was very important to us to get him released," says Kalugin, the former KGB general. "Both morally and to show our loyalty to the people we sent."

But all of that was to no avail. Klingberg served out his full 20-year sentence (some of it on house arrest) and left Israel upon his release. He died in 2015.

Responses

Yedioth Ahronoth was unable to get a response from Shlomo Shmali's family by the time of publication.

Ya'akov Riftin's son said in response, "This never happened. I'm telling you: This is nonsense."

Moshe Sneh's son, Efraim, said in response, "This never happened. During the aforementioned time, my father was not a member of the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee, nor did he have access to classified information of any kind.

"The entire Mapam camp was under constant persecution by the Shin Bet, and they were not given any access to state secrets.

"Anything he may have said about Sharett, if at all, was known information and not at all classified. My father met with Soviet Embassy personnel, but did so in an open manner and without hiding his thoughts and opinions, which were decisively against Mapai (Israel's Labor Party at the time) and Ben-Gurion's pro-American orientation."

It's important to note that in his book "Soviet Espionage in Israel," Isser Harel dedicates an entire chapter to the discussion of whether or not Sneh was a Russian spy. Harel writes about the former MK with a combination of admiration and disgust, but reaches the conclusion Sneh did not operate as a KGB agent.

Dan Granot, Elazar Granot's son, recently recalled how "for a year before the Six-Day War, (Soviet diplomat) Yuri (Kotov) would come to the kibbutz every Thursday in a diplomatic vehicle with a driver. He would bring high-quality vodka and excellent Hungarian sausages with him. My father loved to drink, and Yuri wasn't bad at it either, and they would sit together for hours on end, talking.

"I like the fact he appears in the Russians' lists, it adds another aspect to his character," Granot added. However, he emphasized, "My father did not have any access to classified information, so even if he had wanted to—he did not have the ability to be a spy."

Shaul Arlozorov, who served as the deputy water commissioner and worked alongside Yaakov Vardi for decades, said in response to the allegations, "It's difficult for me to believe these things are true. For 30 years—if not longer— Yaakov dealt with the water-related relationship between Israel and its neighbors—Jordan, Syria, Lebanon and the Palestinians. He was also deeply involved with the National Water Carrier, which was undoubtedly one of the more explosive topics at the time. Great intelligence efforts were invested to know what we were doing there."

Regarding the agent "Malinka," the Shin Bet said in response: "The information from the Mitrokhin Archive concerning Israel regarding the early 1970s is known to the Shin Bet. So far, no information has been found in the Shin Bet archives that confirms the claims raised in the article."

Despite several appeals in Russian to the St. Petersburg Church, no comment was received regarding Archbishop Adrian Oleynikov.

Journalist Aviva Stan's daughter, Talila Stan, said in response: "You don't say! These are simply fantastical stories. It's absolutely wonderful, but I find it hard to believe it. Mother was a colorful character, but not that colorful. I say this, despite the fact she was sometimes invited to diplomatic parties by the Soviets and at times hosted Soviet diplomats. She was a social butterfly."

Research and translation from Russian by Will Styles, Alexander Tabachnik, Yana Sofovich and Yael Sass.

The writer would like to extend his gratitude and appreciation to Prof. Christopher Andrew and Dr. Peter Martland of Cambridge University.