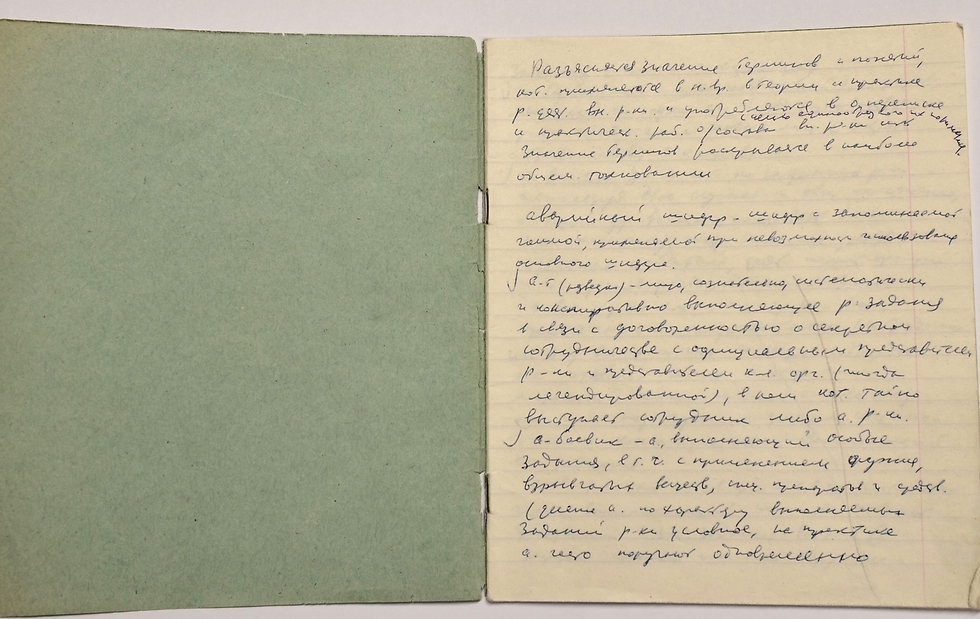

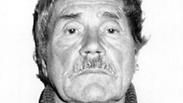

Vasili Mitrokhin upon defecting to the West in 1992

Secret documents expose Israeli politicians, senior defense officials as KGB spies

Thousands of documents copied and smuggled to the West by a former KGB archivist reveal the Soviet intelligence agency's network of agents and assets in Israel, including 3 MKs, an IDF major general and a Shin Bet officer. The full story will be published on Friday on Ynetnews.

Three MKs, senior IDF officers—including a major general—engineers and employees working on classified military projects, and intelligence officers were just a handful of the agents and assets the KGB operated in Israel, according to secret documents obtained by Ynetnews.

These secret documents were copied over the course of nearly 20 years and smuggled to the West in the early 1990s by Vasili Mitrokhin, a former KGB agent who became a senior official in the Soviet intelligence agency's archives.

Mitrokhin became disillusioned with the organization after being exposed to the great purges carried out by the Soviet regime. "I began reading about the mass cleansing and the horrible means of oppression used against the Soviet people, and I could not believe such evil," he said after defecting to the West.

While risking his life, Mitrokhin hid the secret documents he had copied in milk jugs under the floor of his dacha in the suburbs of Moscow.

In 1992, he, his family, and the trove of documents in his possession were smuggled to Britain.

These documents led to an earthquake in intelligence agencies all over the world: Spies were exposed and captured in the UK, France, Germany, the US and elsewhere, while Russian intelligence suffered the greatest blow in its history. Some 1,000 Russian agents are estimated to have been exposed by these documents thus far.

In the days before Edward Snowden and WikiLeaks, Mitrokhin's leak was considered one of the biggest of its kind in the history of intelligence agencies the world over.

The documents also include a lot of information pertaining to the KGB's wide-scale activity in Israel, but most of them have not seen the light of day—until now.

Ynetnews's Hebrew-language print publication Yedioth Ahronoth received access to the documents that are housed at Churchill College's library in Cambridge, where a small team translated and analyzed the information concerning the KGB's activity in Israel.

These documents reveal, for the first time, the amount of time and resources the KGB invested in attempts to infiltrate Israel's centers of powers, which in many cases bore fruit.

Infiltrating Mapam

Israel's political parties were one of the main targets marked by the Soviets. In the beginning of the 1950s, the Russians launched a wide-scale operation codenamed "Trest" to infiltrate Mapam (the United Workers Party).According to the Mitrokhin documents, they were quite successful and were able to recruit no less than three MKs into their ranks.

One of them, who appears in the Mitrokhin documents under the code name "Grant," was described as living “in Kibbutz Shoval, near Be'er Sheva." According to the documents, this was the writer and senior politician Elazar Granot, who also served in the Foreign Affairs and Defense Committee and as the party's secretary-general.

Mitrokhin's documents indicate that Granot was recruited just before the Six-Day War by senior KGB officer Yuri Kotov, and contact with him was cut when the Soviet Union severed diplomatic relations with Israel after the 1967 war.

Dan Granot, the MK's son, recently recalled how, as a child, he witnessed his father's late-night meetings with Kotov, who "would come to the kibbutz every Thursday in a diplomatic vehicle" and "would bring high-quality vodka and excellent Hungarian sausages with him."

However, Granot emphasized, "My father did not have any access to classified information, so even if he had wanted to—he did not have the ability to be a spy."

Recruiting engineers

The KGB's operations in Israel weren't exclusive to the political sphere. It can also be inferred from Mitrokhin documents that the organization recruited an agent codenamed "Boker," who was a senior engineer working on the National Water Carrier project in the early 1950s. The project was considered a top secret and was marked as a top target by the Russians.Another agent, codenamed "Jimmy," was a civil engineer appointed to a classified position in the Israel Aerospace Industries' Engineering Division that, at the time, was working on the planning of their top-of-the-line Lavi fighter jet.

Yet another agent was an engineer working on the maintenance and upgrade of the engine for the Israeli-made advanced Merkava tank.

The list of KGB agents and assets also includes several journalists and one mysterious intelligence officer, who received the nom de guerre "Malinka." Mitrokhin documents state that "Malinka" is believed to have been working in the Shin Bet's Counterintelligence Division.

But one of the recruitments documented in Mitrokhin's trove stood out above the rest: The Soviets were able to recruit a major general in the IDF, who was a member of the General Staff.

In 1992, when Mitrokhin and his documents arrived in London, British intelligence passed on the information about that major general to the Shin Bet.

Yaakov Kedmi, the head of Nativ—an Israeli intelligence organization that maintained secret contact with Jews living in the Eastern Bloc during the Cold War and encouraged immigration to Israel—at the time, recounts, "The Shin Bet didn't tell me the name of the major general, but I understood from them how great the shock upon receiving the update from the British was.

"Because of that major general's health situation, and I believe also because of the embarrassment the IDF and the State of Israel would have suffered had this story come to light, a decision was made not to take action against him and not to prosecute him. He passed away shortly thereafter."

The full story on the Mitrokhin documents and the KGB's agents in Israel will be published on Friday morning in English on Ynetnews, and in Hebrew in Yedioth Ahronoth's 7 Days supplement—both in print and in the paper’s app.