Newly published documents reveal how Western Wall was renovated in 1967

An exchange of letters and a first architectural map of the holy site’s plaza upon its liberation are being exposed for the first time ahead of the 50th anniversary of Jerusalem’s reunification; ‘The fact that the Ministry of Religions was tasked with the renovation turned the place into an Orthodox synagogue,’ says architectural historian.

For years, Eshkol’s wife kept the letters correspondence regarding the decision on how to run and renovate the Western Wall. They have been kept in the Yad Levi Eshkol archive, and are being exposed here for the first time ahead of the celebrations of the jubilee of Jerusalem’s reunification.

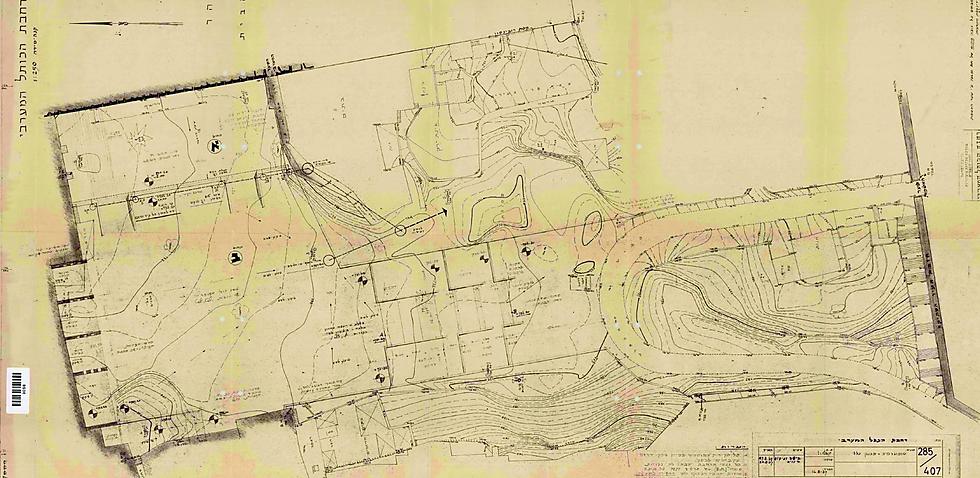

They include a first architectural map of the Western Wall Plaza upon its liberation and the plans for what it would look like after the destruction of the Mughrabi neighborhood—and in preparation for visits by millions of worshippers.

Since the liberation of Jerusalem’s Old City in the Six-Day War, many architects tried to plan what the Western Wall Plaza and its surroundings would look like and what would be there.

The prime minister’s decision at the time on who would be given the responsibility to manage and renovate the Western Wall Plaza had consequences which affect, to this very day, the nature of the holiest place to the Jewish people.

Donations between the Western Wall stones

At the end of the war, a dispute broke out between the National Parks Authority and the Ministry of Religions over who would be in charge of the Western Wall expansion works and who would manage the site.

The National Parks Authority saw the place as national park, while the Ministry of Religions insisted that it was a site of religious nature and that the ministry should therefore be responsible for it.

Then-Prime Minister Levi Eshkol ruled in favor of the Ministry of Religions, and architect Yosef Scheinberger was appointed by Minister Warhaftig to outline a first plan for regulating traffic at the Western Wall and making the site accessible to millions of believers from around the world.

Planning elements began resisting the plan, becoming the first objections to many plans that were submitted and have not been completed to this very day.

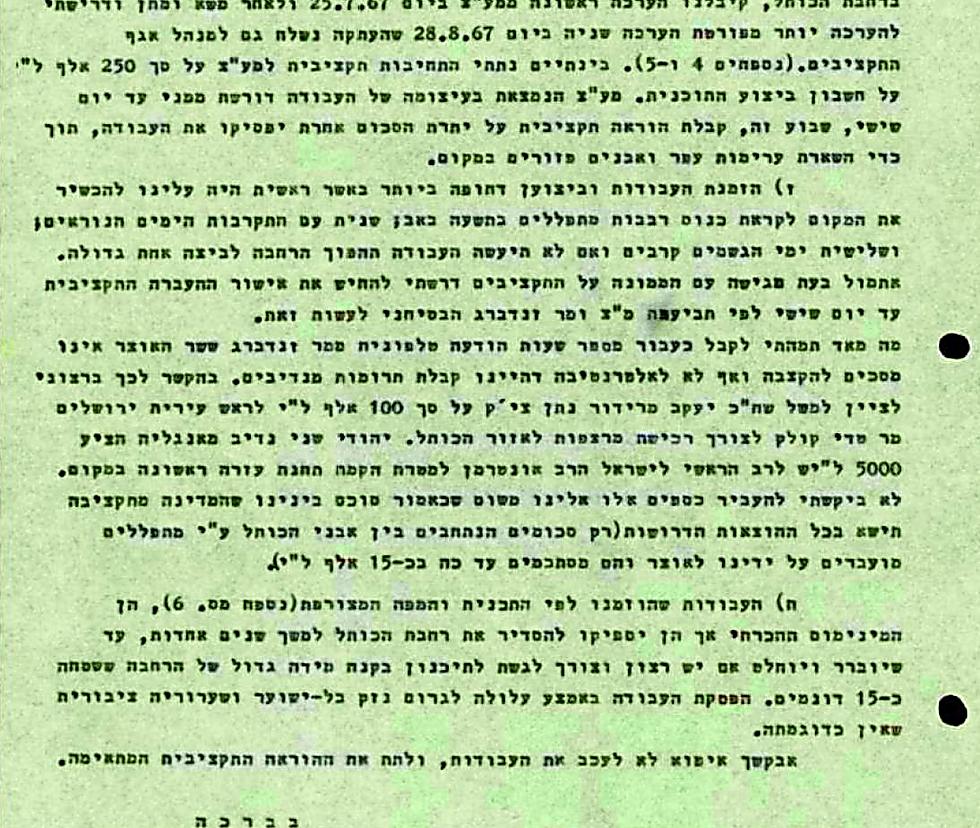

The then-minister of religion wrote to the Finance Ministry, “Commissioning the work and performing it is extremely urgent, as we should have first of all prepared the place for the assembly of tens of thousands of worshippers on Tisha B’Av; second, due to the approaching High Holy Days; and third, due to the approaching days of rain, and if the work is not done, the plaza will turn into one big swamp.”

He complained about the holdup of funds for the work, which costs a total of 680,000 Israeli pounds—and despite the Treasury’s ban on receiving “donations from benevolent people.

“In this context, I would like to mention, for example, that Knesset Member Yaakov Meridor gave Jerusalem Mayor Teddy Kollek a 1,000-pound check for the purchase of tiles for the Western Wall area,” he wrote. “… A philanthropist from England offered Israel’s chief rabbi 5,000 pounds sterling for the establishment of a first-aid station at the site.”

He noted that he had not asked for those funds, as it was agreed that “the state would bear all the required costs.” So what was transferred to the Ministry of Religions? “Only sums inserted between the Western Wall stones by worshippers,” nice donations worth 15,000 pounds.

A 3.60-meter prayer plaza

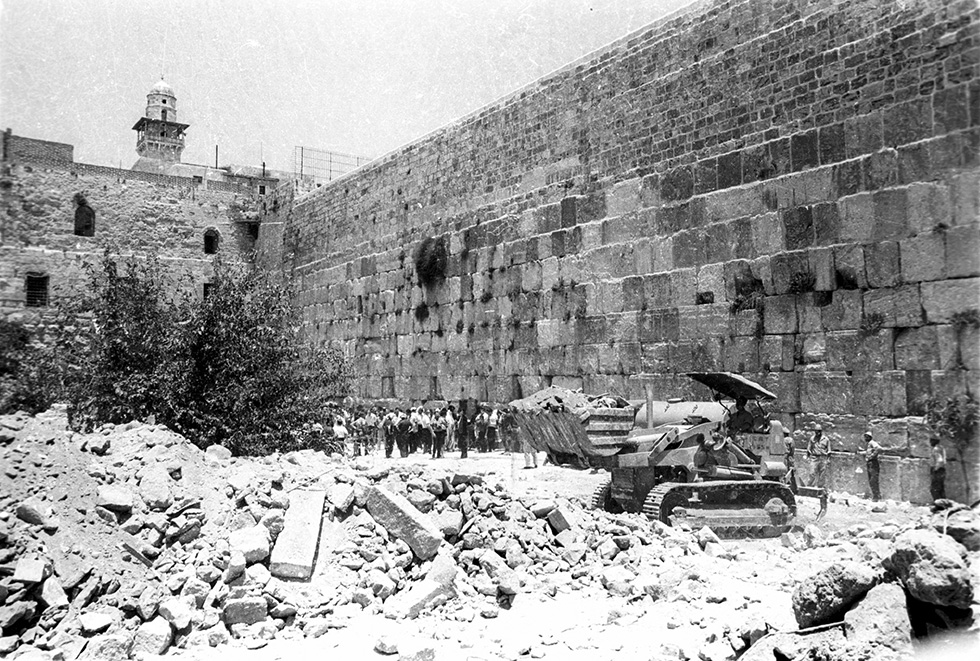

According to Prof. Alona Nitzan-Shiftan, an architect and an architectural historian from the Technion, who reviewed the documents, “On the night of June 10, 1967, the last night of the war, IDF bulldozers demolished the Mughrabi neighborhood located near the narrow alley. After the neighborhood’s destruction, the Western Wall Plaza was 3.60 meters wide.

“The place looked like piles of rubble, and there was a need to prepare the area for the arrival of millions of people from Israel and from the world who wanted to come for the first time to the Western Wall under Israeli sovereignty. The plan we see here includes no big changes: There was a decision to separate the prayer plaza from the general visits plaza, and one can see a listing of the accessibility arrangements to the Western Wall and to the prayer plaza. There are notes on the wall’s supporting walls.”

Nitzan-Shiftan adds that “the important part of the plan was lowering the prayer plaza and separating between women and men. The fact that the Ministry of Religions was tasked with carrying out the work at the plaza, as the responsible element, turned the place into an Orthodox synagogue. This may not have happened had then-Prime Minister Levi Eshkol transferred the authority to manage and renovate the plaza to the National Parks Authority.”