It's April 6, 2006, at five o’clock in the afternoon. Halit Yozgat, a 21-year-old German citizen of Turkish descent, is sitting behind the counter in the small Internet café he recently opened in Kassel, Germany. He is waiting for his father to come and relieve him from work when two shots pierce his head, killing him instantly.

A few seconds later, Andreas Temme, an undercover agent for the German Federal Intelligence Service, the BND, gets up from one of the computer stations positioned only several meters from where Yozgat is now lying dead. He places a few coins on the counter as payment for his time there and leaves. Next to the coins are three drops of blood.

Later, Temme will testify that he did not hear the shots—fired by an unknown assailant with a Česká manufactured pistol with a silencer—and he did not see Yozgat’s body, either, which was sprawled behind the counter near the entrance.

In the weeks and months that followed the incident, a brilliant young lawyer in Munich named Yavuz Narin, also of Turkish descent, has been fervently following the details of the case. The presence of a German secret agent at the scene of the murder does not surprise him. On the contrary, it supports his theory, the biggest conspiracy theory in German history. Narin decides to solve the case himself.

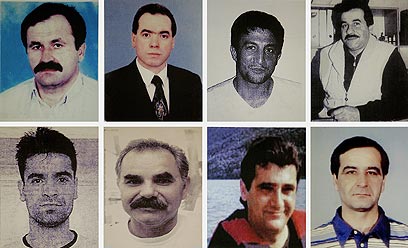

Yozgat was the ninth victim in a string of unsolved murders dating back to 2000. A Česká pistol was used in all of them, all of the victims were immigrants—usually Turkish—and owners of small businesses, and all of them were shot in the face at point blank, in broad daylight, in the center of large cities across Germany.

The police’s working assumption was that these were assassinations by the Turkish mob. Investigators spent years pressuring the victims’ families in an effort to get them to confess to ties with the criminal underworld.

These investigations were accompanied by racial stereotypes: the special investigation team was called the “Bosporus Unit,” referring to the ethnic Germans living and settled in Istanbul, while the assassinations were referred to in the German media as the “Döner Killings,” named after the popular Turkish-German shawarma dish.

The few voices suggesting to consider alternative lines of inquiry—for example, that the murders were hate crimes perpetrated by far-right extremists—were largely ignored. Even when a pipe bomb detonated in Cologne in 2004, the police did not divert their investigation from its original course.

The Pink Panther sends his regards

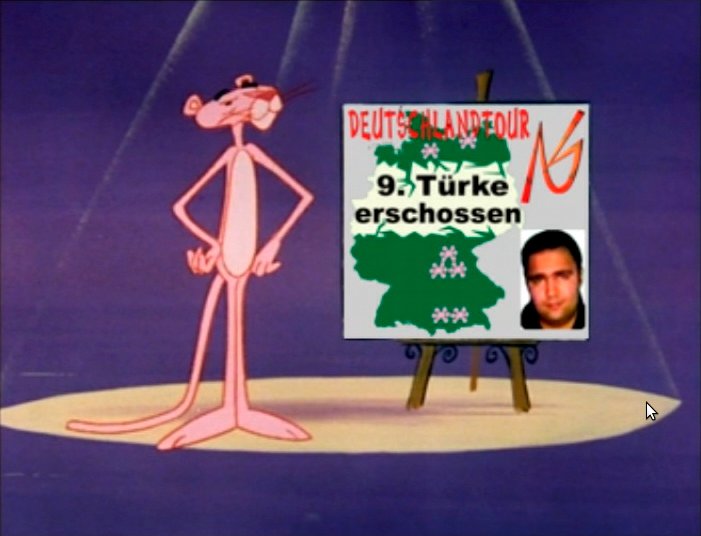

The case took a sharp turn on November 2011, when a number of news agencies received a strange 15-minute video. The video showed the Pink Panther walking down the street to the tune of the familiar theme song, stopping in front of a sign that read “Stand with your country. Stand with your people.”

The lovable pink icon is then seen planting bombs and assassinating people, as the cartoon scenes switch to real footage of the crime scenes from the “Döner Killings” and the Cologne bombing.

The video ends with the Pink Panther lounging on his couch, yawning and watching real news reports about the cases, showing the police’s inadequacy in solving them. Finally, it shows the mark of the National Socialist Underground (NSU).

After years of in which police have been investigating dead ends, the murderers decided to mock them in public by bragging and telling them precisely who the real culprits behind the unsolved cases were.

A few days before the video was released, a bank in a small town in east Germany was robbed. The two robbers escaped the scene on bicycles, which they hid in a car parked nearby—just as they have done dozens of times before. Only this time, they aroused the suspicion of a passerby who called the police. When the police arrived, they heard gunshots and then the vehicle went up in flames. The bodies of two far-right activists, Uwe Mundlos and Uwe Böhnhardt, were found inside it.

Shortly thereafter, there was a loud explosion at the apartment the two were sharing with their friend and fellow activist Beate Zschäpe, who turned herself over to the police a few days later.

Police searched the burnt apartment, finding copies of the Pink Panther video, newspaper cutouts about the murders, and the Česká pistol. Later, police learned that Zschäpe was likely the one who distributed the Pink Panther video to news agencies when she realized that the NSU was nearing its end.

The case was allegedly solved: the trio behind the murders and their group were uncovered. The trial of Zschäpe, the NSU’s last survivor, began in 2013.

Combat 18's modus operandi

Yavuz Narin did not get much sleep before the interview, but he hid it well with his exuberant self-confidence. “When the trial began, the media described me as ‘the young lawyer Narin,’ but not so much anymore,” the 39-year-old says with a chuckle.Narin is representing the widow of one of the victims, Theodoros Boulgarides, a 41-year-old locksmith of Greek descent who was shot at the entrance to his store in Munich. Though, the lawyer was curious about the case even before knowing the murderers were radical nationalists.

“My interest in neo-Nazi terror groups began when I was still a student,” he reveals. “One of these groups was called Combat 18 (C18). They used to plant nail bombs in immigrant neighborhoods there.

“A few years later, in the summer of 2004, a nail bomb blew up in a predominantly Turkish street in Cologne. Videos and police facial composites showed blond-haired criminals who arrived at the scene on bicycles. The only group in Europe who was using nail bombs at the time was C18. I thought to myself ‘We have a German C18!’ I figured the police are going to uncover them in a few days. But I kept following the case—and nothing happened.

"Then it hit me: in the string of unsolved murders, which back then were still referred to as the 'Döner Killings,' skinny blond-haired men were spotted riding a bicycle near the crime scenes. I remembered that, aside from planting nail bombs, C18 also used to assassinate people by shooting them in the face at point blank.

“I then thought to myself, ‘these are the exact same people.’ It was then that I finally got it. I thought that if I figured it out but the police didn’t, something here was fishy.”

It later transpired that C18 cells did apparently assist the NSU in Germany, but Narin’s insights were considered wild conspiracy theories in 2004 and even years afterwards.

“When I started representing Boulgarides’ widow back in 2011, a short time before the whole case blew up, I told her from the start that I believed her husband did not have any ties to the criminal underworld; that we were dealing with a neo-Nazi organization; and that the explosion in Cologne was part of it," he recounts. "Years later, she told me that even she thought that I was crazy."

Narin has develop an unusual work method. Unusual for a lawyer, that is. “More often than not, the police investigations were not sufficient, and so when the police were done with the investigation, I drove up to the scene and continued it from where they left off," he says.

“I’ll give you an example: the police looked for some neo-Nazi as part of their investigation and could not find him for about 18 months. I decided to drive by myself to his old apartment, in a small village in east Germany. I asked around, talked to a few of his neighbors. I managed to find him in four hours. In these kinds of villages, it’s best to ask the grandma who are sitting by their windows. They’re better than any secret service. They keep track of who comes and who goes, who talks to whom…"

“I do research on the internet and on social media and then just drive to where I think I’ll find answers," he continues. "Maybe that’s just too much work for the police. Sometimes, I even go to demonstrations by the National Democratic Party (NPD—Germany’s a far-right and ultranationalist political party). I look for specific people and talk to them directly. In one instance I arrived at night to a neighbor of the NSU trio and just knocked on the door. A huge guy opened the door in his underwear, covered from head to toe in Nazi tattoos."

When asked if it scared him, Narin responds casually. “No, at most they could take my life. People die all the time. A friend of mine died this year of cancer. There is a Turkish saying that ‘fear does not protect you from certain death.’ I learned to let go of fear, because it gives you bad advice, it clouds you judgment. I also took Israeli Krav Maga self-defense lessons in the pasy, so I feel comfortable in all sorts of places. My appearance, too, which usually projects a lot of self confidence, make it so that I don’t have much to fear.”

Fear of security agency-backed Nazi terrorism

The NSU trial is considered one the most complex cases in Germany. Zschäpe, as the only survivor of the group, is the main suspect, and there are several other suspects who have been accused of assisting her.Four years in, this is the longest criminal trial in Germany’s history. The trial includes about 600 witnesses who have given testimony so far, as well as over 80 plaintiffs represented by over 60 prosecutors—Narin being one of the most prominent among them.

There were 13 committees of inquiry, both government- and district-appointed, looking into the case. However, despite its endless complexity and despairing length, the case still holds the public’s interest. All major newspapers in the country devote regular columns to it, special organizations were established to document it and even shows and exhibitions were made about it. The trial has now entered its final stage.

“The complexity of the case stems from the fact that it involves a series of crimes spanning over an entire decade and includes ten known murders, three terrorist bombing attacks, and 15 robberies,” explains Narin. “Beyond that, it includes a large number of supporters and accomplices who assisted the terrorists.

“In addition, the secret service and the police played a problematic role in this case. For a long time, there were no less than 25 informants—people who worked for either the police or the secret service—in the trio's close circle. Some of them even provided the group with weapons, funding, explosives and shelter. The secret service is still protecting all of these informants. Their identities are kept secret at times, documents arrive late, if at all, and agents and informants are usually barred from testifying. In that regard, it is a very unusual trial, and it’s very hard to fully uncover the truth.”

The involvement of security services with the NSU continues to rile up the German public, and is still under a heavy clout of secrecy.

'Little Adolf'

The use of informants is a common practice by German secret service agencies. Paying informants is obviously a controversial issue, as it means that criminals are provided with funding and immunity from prosecution. Far-right activists in Germany acting as informants have been paid vast amounts of money over many years, and in practice tax payers' money went to aid far-right organizations in their activities no less than it did the secret service’s efforts to gather intelligence on them.The worrying question that arises is whether the German security agencies merely failed at doing their job, or did they actually turn a blind eye and intentionally enabled the NSU’s activities. And if so, could neo-Nazis have infiltrated Germany's spy agencies and actively encouraged the crimes? The authorities’ insistence on covering up information and stonewalling investigation on the matter only raise further suspicions.

An example for that is the case of Andreas Temme, the German intelligence agent and handler who sat at the Internet café when Halit Yozgat was murdered.

According to Temme’s testimony, he was there completely by chance. However, it is very unlikely that he did not hear the gunshots, managed to miss Yozgat dying on the floor, and failed to notice the blood on the counter.

Recently, however, researchers at the London-based Forensic Architecture agency, using advanced technological means, were able to prove that based on the layout of the crime scene, Temme not only heard the gunshots, he also must have smelt the burnt Cordite (the bullets’ ignited propellant, formerly gunpowder) and seen Yozgat’s body.

Yozgat's murder investigation revealed that Temme was speaking to a far-right informant an hour before the murder. In addition to that, a search of Temme’s home uncovered Nazi and anti-Semitic literature, illegal firearms, drugs and evidence tying him to the local neo-Nazi circles.

Acquaintances from his home town even testified that in his youth, Temme was known as “Little Adolf.”

Despite all that, his defense team and the German security services blocked any attempt to indict him. Like Temme, no other German official who was involved in the case has been prosecuted.

When Temme was asked why he did not even report to the police that he was at the scene of the murder, he responded that he was ashamed to admit to them that he was spending time there browsing dating websites while his wife was pregnant.

Narin has many more examples of either direct or indirect involvement by security agencies in the NSU’s activities. Over the years, he traveled all across Germany, found witnesses and uncovered documents, and made connections with investigative journalists, agents and former agents, policemen and neo-Nazi activists. It was thanks to Narin's stubborn persistence that the focus of the trial has been greatly expanded from the three lone criminals to a vast and active network that has deep roots in government mechanisms.

Narin still believes, and now with good reason, that “the government, security agencies, the Interior Ministry and, unfortunately, even the Chancellor’s office, are trying to prevent a full investigation on the matter.”

“Any time that the authorities seem to be either involved or implicit, the Public Prosecutor General's office stonewalls us. For years, when the crimes were still being attributed to the Turkish mafia, the authorities said that there is a ‘wall of silence’ around the victims. Today we know that the victims’ families knew nothing, and that the ‘wall of silence’ was actually around the authorities. To learn the truth, we must confront the authorities.”

The pressure the authorities put on the families of the victims was dubbed by the German press as “the Second Trauma.” Boulgarides’ widow, who is represented by Narin, was repeatedly questioned. Police told her that her husband was involved in drug trade, prostitution and gambling, and they even checked whether he sexually abused his own daughters. She was even asked if she was the one who murdered her husband. It is now clear that there isn't a shred of evidence to any of these allegations.

Murders of compromise

In March, Narin’s investigation uncovered another dimension to the NSU. In 2000, several months before the murders started occurring, a young woman attracted the attention of a policeman patrolling near the Central Orthodox Synagogue in Rochstrasse, Berlin—the biggest synagogue in Germany. “When I looked at the young woman, she stared back at me with a look filled with venom,” the officer wrote in a report he filed the very next day.

The young woman was seen sitting with three other individuals at a restaurant near the synagogue. The four were looking at maps, while two small children were sitting with them.

That same evening, by complete chance, the officer was watching a TV show about unsolved crimes in Germany, which featured photographs of Zschäpe, Mundlos and Böhnhardt—the same three NSU members who disappeared after a string of crimes. The NSU trio looked awfully similar to three of the four individuals from the restaurant, prompting the police officer to report the incident.

Narin tracked down the officer and his report, and even managed to uncover the identity of the fourth individual who was at the restaurant that day—Jan Werner, who at the time was head of the neo-Nazi organization Blood & Honor.

He too, entirely not by chance, was a paid police informant and apparently supplied the NSU with weapons and money. The Public Prosecutor General's office, as expected, fought against including this evidence in the trial.

Several months after the gathering near the synagogue, the string of murders began. “They chose to kill defenseless people out of cowardice. The synagogue was apparently too difficult of a target for them because of its tight security,” says Narin. “Anti-Semitism is at the heart of the NSU. Investigators found hundreds of different addresses of Jewish targets in documents seized from the NSU.”

According to official data released in March, Germany had an average of ten assaults against refugees per day in 2016. In the 1990s, Turkish immigrants were the target of such attacks; today, it's Syrian and Afghan refugees.

“Fear-based hatred of immigrants exits in many countries, and yes, Germany is among them,” Narin says. “Today, though, we’re doing much better compared to how we did in the 1990s, as back then those attacks were often left uninvestigated. It is largely due to efforts of brave lawyers who turned crimes considered to be trivial into serious offences, which actually gain attention.”

(Translated & edited by Lior Mor)