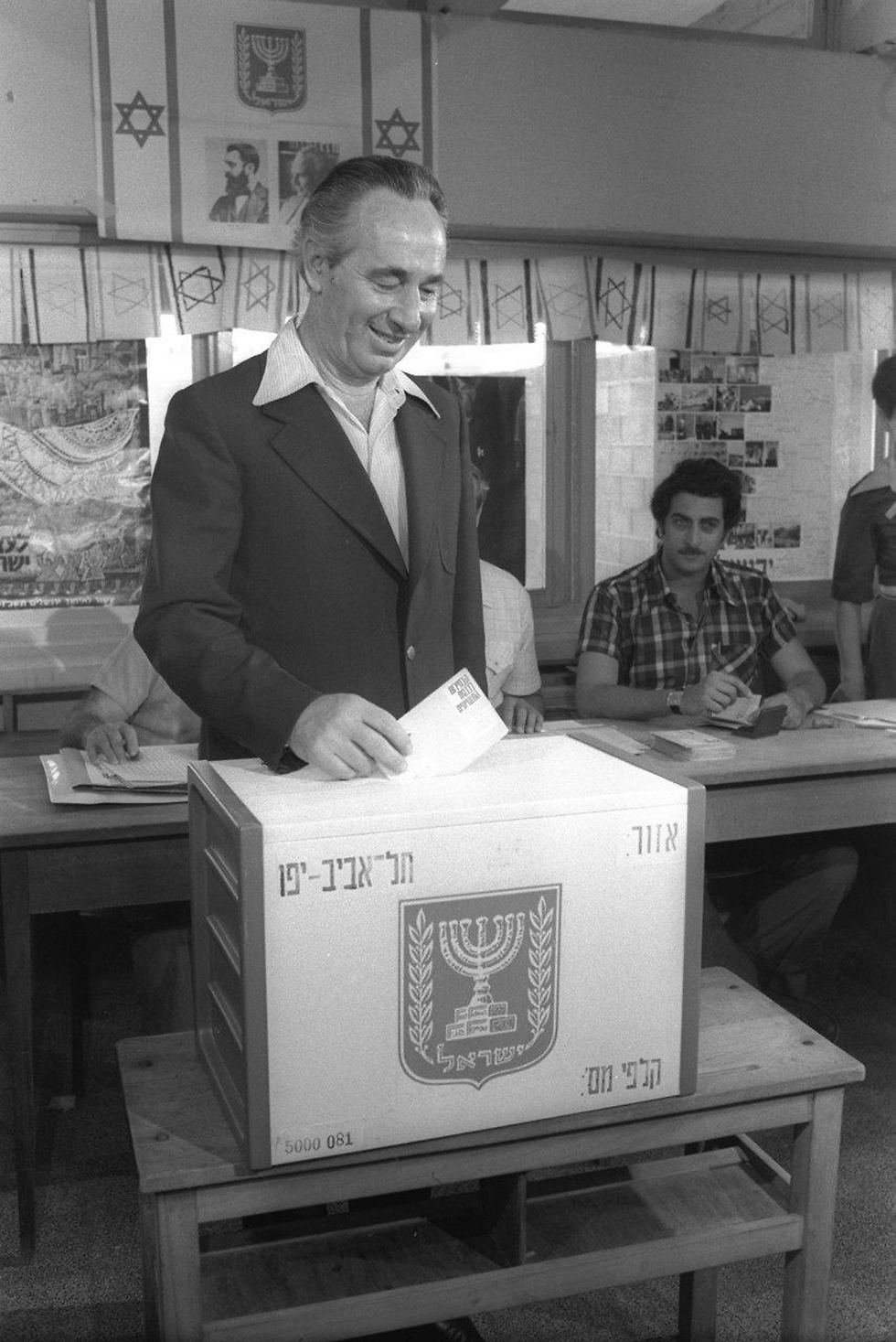

Peres in his own words: 'You could be dead while you're alive, and you could also live after your death'

In the months before Shimon Peres's passing, journalist Amira Lam held a series of meetings with the man who was the last of Israel's founding fathers. During their talk, Peres opens up about the Dimona reactor, his relationship with Rabin, and the settlements.

"Death is a question that has no answer, so I don't deal with it. President François Mitterrand told me in one of the conversations we had before his death that we all know that we will one day cease to be. The real problem is not death, but life. You could be dead while you're alive, and you could also live after your death."

In the months that preceded his passing, I held a series of meetings with Shimon Peres. The objective was to gather material for a movie, perhaps a docudrama, to tell his life story, with a famous actor to play him. The idea amused him, and every now and again he would joke with me about the choice of actor, debating between Robert Redford and Kevin Costner.

Peres understood that the time he had left was limited, but refused to let that come into our meetings. No interview, as far as he was concerned, was a goodbye interview, and no conversation was his last. The conversations with him were fascinating. He knew how to tell a story, and he had many stories to tell.

But it was actually in our last few conversations, perhaps because of the movie, that Peres felt comfortable to speak with greater candor. The years of his life unfolded before us like a great drama—from sailing against the wind in the early 1950s when he established the Israel Aerospace Industries, through the Entebbe Operation and his attitude towards the settlements, to his complicated relationship with Yitzhak Rabin, which ended with a hug right before he was murdered.

Peres allowed himself to say things he never said before, at least not in public: on what happened when he visited the settlement in Sebastia near Nablus, the forged document that convinced the French to build a nuclear reactor for Israel, and his insistence not to bring the United States in on the secret of the reactor without first consulting with the French.

Most of our conversations took place after he left the President's Residence. Peres didn't have an official position, but his schedule was still packed with meetings, lectures and interviews. Usually, we'd meet at his office at the Peres Center for Peace. We almost always scheduled the meeting for an hour and a half, but ended up talking for two, after which he would abruptly slap his hand on the table and say "That it's, we're done for today," get up, and leave.

From one meeting to the next, Peres grew weaker. This weakness was mostly apparent in his voice. Sometimes, when his memory betrayed him, and he forgot a date or a place, he'd tell me: "We need a new division of labor between man and computers: Let the computer remember and man dream. Man doesn't need to remember, there's someone to remember for him. Leave me to dream."

'The problem in life is not what to be, it's what to do'

When I asked Peres if it was hard for him to leave public life, he responded: "What's easy? What's hard? People sometimes think that going on vacation is easy. Me, as I always say, it bores to death. Everything is relative, even what it means to be happy. To me, peace brings more happiness than money. There's a greater gain in love than in your bank account. The problem in life is not what to be, it's what to do."

And even though at the time we were still six months away from the US election, Peres added, "The problem is that in Israel, there's a cult around the government. But it won't be Donald Trump who ends up running the world, even if he wins the election. Mark Zuckerberg and Facebook will run the world. Because what runs the world today is a new mechanism of global companies that hold the money and the power.

"In this world, there are also elements outside of government that make decisions. We don't need governments for that. My optimism today comes from my faith in those global companies. On the one hand, there is a wave of xenophobia and nationalism prevalent today. You can see it with Brexit and in Turkey, in the power that Trump is gaining. There will always be waves like that over the course of human history. But if these waves continue, we'll go back to borders, wars, mistakes. That will be stupid for the world to do. Science has no borders. That is why I believe that in the end, the new world of science will win, not the one of nationalism.

"However, if we were to return to me and the fact I have no public role, it would be quite the opposite. Ever since I left the President's Residence, I've been feeling that I needed to work even harder. In general, I believe a person should work. Not stand in front of the mirror all day and examine how he looks, how he feels, and how he's seen. That's not interesting. The politicians of today are too preoccupied with that; unfortunately, they're mostly focused on themselves."

'The settlers still don't heed the government's orders'

I asked Peres if there were things he regretted, and what mistakes he had made. "I don't have regrets for a simple reason: there's no value or use for them. What are you going to do with regret? It's self pity. The French say, 'It's better to be sorry than to regret.' There's nothing I've regretted."

I asked him about the settlements, reminding him of Sarah Nachshon, who held her son Abraham's circumcision at the Cave of the Patriarchs, defying government orders. Sadly, the baby died several months later, and she insisted on burying him in Hebron. Peres, the defense minister at the time, authorized the burial.

Some say your authorization led to renewed Jewish burial in Hebron. This is an issue you haven't discussed. Have you repressed it?

"It's the kind of moment you don't forget. Even if I haven't spoken about it all these years, it's stayed with me. But let's look at the big picture: A woman walking with her dead child, wrapped in blankets and embraced in her arms, passing by checkpoints, walking and walking. I did the math. I oppose the settlements, but you also need to know what are the exceptions to the rule. A man holding a hammer thinks every problem is a nail. In this case, there were emotions involved: a grief-stricken mother who had lost her son. So even if you do have a hammer, not everyone is the same nail. This is an incident I remember and go back to in my thoughts. She marched, charged forward, didn't listen. The soldiers at the checkpoints didn't know what to do. She was determined and grief-stricken. I didn't want her to be hit or arrested. So she was allowed to make an unusual decision for humane reasons. That's what I did, and I think I did the right thing, even if it is a moment I think back on a lot."

Peres knows the Left never forgave him his part in the establishment of the settlement enterprise. During our conversations, he unloaded the burden he has been carrying for years. He revealed that the instructions came from people who were at the time part of then-prime minister Yitzhak Rabin's close circle of advisors.

"I went to Sebastia to demand that (the settlers—ed) leave," he says. "When I got there along with then IDF chief of staff, Motta (Mordechai) Gur, we were welcomed with clapping and singing. I told them: 'Dear friends, you're mistaken. I didn't come here to ask you to stay. I came here to demand that you leave. And then Rabbi Levinger, who was the leading figure there, tore his clothes in mourning. They started shouting at me.

"When I was Yitzhak Rabin's defense minister, he appointed two advisors: Arik Sharon and Gandhi (Rehavam Ze'evi). Both were right-wing, both supported the settlement enterprise, and both led the battle against me from the Prime Minister's Office. The settlers insisted on not leaving. While we were sitting and talking, legions of settlers started filling the surrounding area. Someone else was advising them against me, instructing them on how to act, and they had been updated on the situation. Motta and I were stunned. We couldn't understand how they knew everything that was happening (in the leadership). Afterwards, the government instructed me to try to reach a compromise with them. Offer them to leave quickly, within a month. I offered that to them, and they rejected it. In the end, it was agreed to postpone the decision by three months."

And what happened after three months?

"What happened was that the settlers didn't heed the government's orders, and to this very day they don't."

But why you did initiate the founding of the settlement of Ofra?

"Because I wanted to establish something there that was similar to the Nahal, have soldiers working and guarding there. Our situation in Jerusalem was weak. We wanted to build a radar station. The settlers came to me and said they wanted to settle in Tall Asur. I said, 'You know what? You'll work at the radar station.' I treated them like the Nahal soldiers."

And now, when you see the entire settlement how do you feel?

"Everyone knows I oppose these settlements—I did then and I still do now. When there was a change of power from Mapai to the Likud, there were maybe 20-30 settlements and 6,000 settlers. At the time, this really wasn't considered a problem. If there were only 4,000 settlers today, we wouldn't be having a problem. But when there are half a million, that's another thing entirely. That happened after we left power. Of course I'm sorry that it exists. You need to understand, I was never a supporter of 'Two banks has the Jordan River, (this is ours and, that one as well—part of the famous Hebrew poem The East of the Jordan by Revisionist Zionist leader Ze'ev Jabotinsky).' My entire life I've believed that a moral Jewish state on part of the Land of Israel was better than being on the entire Land of Israel but in a state of perpetual conflict.

"This remains the most contentious issue between us and the world. Because the UN decided on two states, provided two maps, and we accepted it. But instead of implementing the two maps, we decided to have just one. The possibility of only having one map is the saddest thing that ever happened to us."

The Left also won't forgive you for not going to elections immediately after Rabin's murder. With the political climate at the time, you probably would have won big. Later, you lost to Netanyahu.

"I wasn't even sure we'd win. Even Rabin won the last election with only a two-seat advantage. It was hard for the Labor party to shake off the image of 'corruption.' Mostly, I was afraid of a civil war. There was a lot of rage among the people at the time. I thought we needed to be more cautious, to calm things down. That was when I was truly afraid a civil war might break out."

'That was the first and last time Rabin hugged me'

His relationship with Yitzhak Rabin was one of the most charged topics I spoke to Peres about. But he sounded surprisingly very serene and sobered, as if he had already made his peace and forgave the man who was his greatest partner and rival.

Do you remember when the hatred started growing between you, or why?

"Everyone views the issues in the relationship between me and Rabin as a personal matter. But in reality, the rift between us started simply over ideological division. The Labor party, which was then called Mapai, was at the time made up of three different camps, and we were from different camps. The first time I saw him, we were still in the General Federation of Students and Young Workers in Israel. Later, he was in the Palmach and I was in kibbutz Alumot and was recruited to the Haganah. I was a (David) Ben-Gurion man, and he was a (Zionist activist Yitzhak) Tabenkin man. We also had some friends in common, one of them was (Mapai founding member) Shraga Netzer's son. He was from Ramat Yohanan, a close friend of Rabin's and a close friend of mine. We saw one another briefly at his place. We weren't friends and we didn't talk much. Even then, there was tension in the air.

"Ahdut HaAvoda, which Rabin belonged to, groomed its people and protected them. In Mapai, which I was a member of, each was on his own. I was seen as an adversary. I know people like to say that he was a Sabra while I wasn't, he was in the Palmach and I wasn't. But that wasn't what mattered. The rift was the result of us being in different camps."

But he had fame from being a Palmach and an IDF man, and you didn't.

"Despite all I did for security, I never asked for anything; not ranks, nor anything else. When they wanted to give me an honorary rank, I refused. I was more interested in other things. Rabin once told me: 'The difference between me and you is that you love building power and I know how to use it.' I, for example, wanted to buy the first computer for the defense establishment. Rabin, at first, opposed it. He said rifles and bullets were preferable. Rabin also objected to the (nuclear) reactor. We really did have two different worldviews. But make no mistake, Ben-Gurion loved Rabin."

And you?

"You have to understand something many people don't understand. The relationship between me and Rabin was asymmetrical. I didn't have any hate. If they do a post-mortem examination on me, they won't find a lot of hate in my heart. The problem, if you ask me, was that Rabin was surrounded by people who incited against me, until he was incited. From a young age, I was vilified for everything. They gave me a hard time. I was lonely and I wasn't famous or anything. And I didn't always know what to do. There was no one to defend me. At a certain point, I made the first strategic decision in my life—that I would decide who I'm offended by. And I decided not to be offended by Ahdut HaAvoda and Rabin. JusIt was simple, though it wasn't easy, it was a process. There were a lot of offenses in the middle. I was slow to get to that point in my mind. Perhaps even a bit too late. There were years that my relationship with Rabin bothered me."

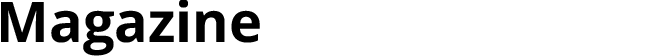

And yet, in the end you were one of the last people that Rabin hugged before his death.

"In the early 1990s, we were both part of the negotiations with the Palestinians. There were peace talks at the time in Washington, but I realized peace will not be made there. There were only press conferences there. I went to Yitzhak and said: Nothing will come out of this, only press conferences. Let me try doing it my way. He said: As long as it doesn't hurt (the existing talks). I gave him my word. Once, he wrote to me asking me to stop halfway through. I wasn't bothered by it. And, as I predicted, the talks in Washington were unsuccessful, while what I was doing was starting to work. Meanwhile, since he was the prime minister, the public viewed this matter—of the Palestinians—which I was dealing with, as something Yitzhak was responsible for. The right wing protested against him. They gave him a hard time. He was miserable.

"I, of course, stood by his side. I saw how he was being humiliated. And then we decided to hold that rally in which he was murdered. He was sure he would lose the elections. By then, we had become much closer. We'd meet in private at his home every Friday. We kept talking about practical matters, and he wouldn't even let (his wife) Leah in the room when we were meeting there.

"When we were organizing that rally, he told me: 'Shimon, I'm worried people won't show up.' It was right after the event at the Wingate Institute where protesters swore at him and after they made a coffin for him in Jerusalem. As you know, a lot of people showed up in the end. It was the happiest day in Yitzhak's life. I've never heard him sing before. He hugged and kissed me. It was the first time Rabin hugged me. The first and the last. In hindsight, it was a goodbye hug. I missed him a lot after that."

Building the Dimona nuclear reactor

What was the biggest decision you've ever made?

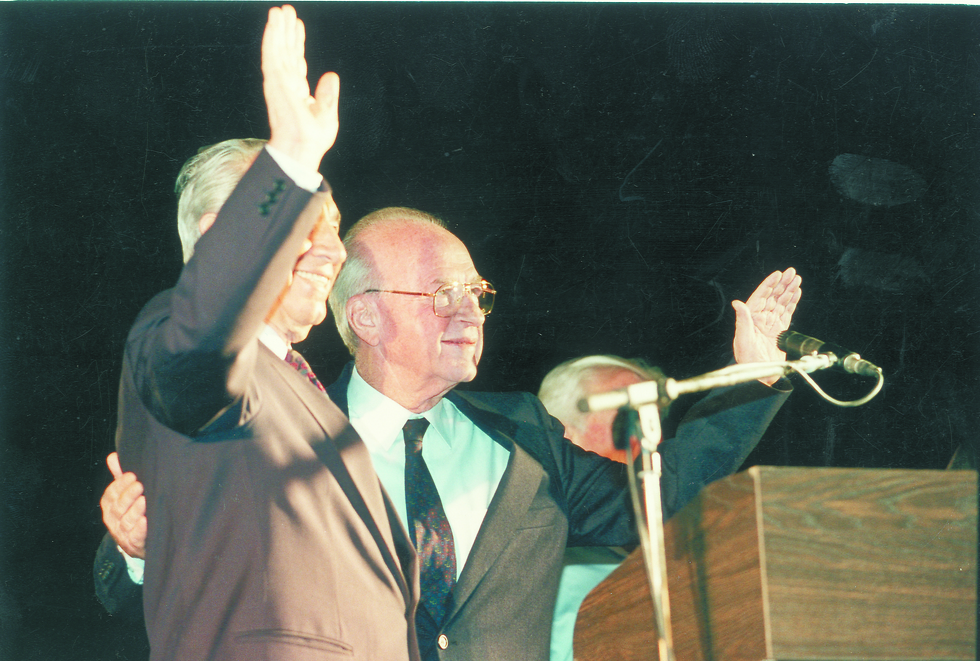

"Primarily, that I would look forward and not back. More than recreating the past, I'm interested in dealing with the future. But the biggest privilege I ever had was working with Ben-Gurion.

"The most important thing I'll ever do in life, I hope to do tomorrow. I'll tell you this without any modesty: Everything I've ever done has always been met not with applause, but with derision. The hardest thing in life has perhaps been ignoring this derision.

"So (the biggest decision) might have been the reactor, which was met with a lot of opposition. It might have been the Israel Aerospace Industries. It might have been Entebbe. And it might have been stopping the inflation.

"No one believed me. No one believed in me. Not just the people on the street; no one believed in me among the leadership, either. The experience I gained with the Dimona reactor allowed me to learn that despite the derision, despite the closed doors—the impossible was possible. "

Is it true the Dimona reactor was built thanks to a forged document?

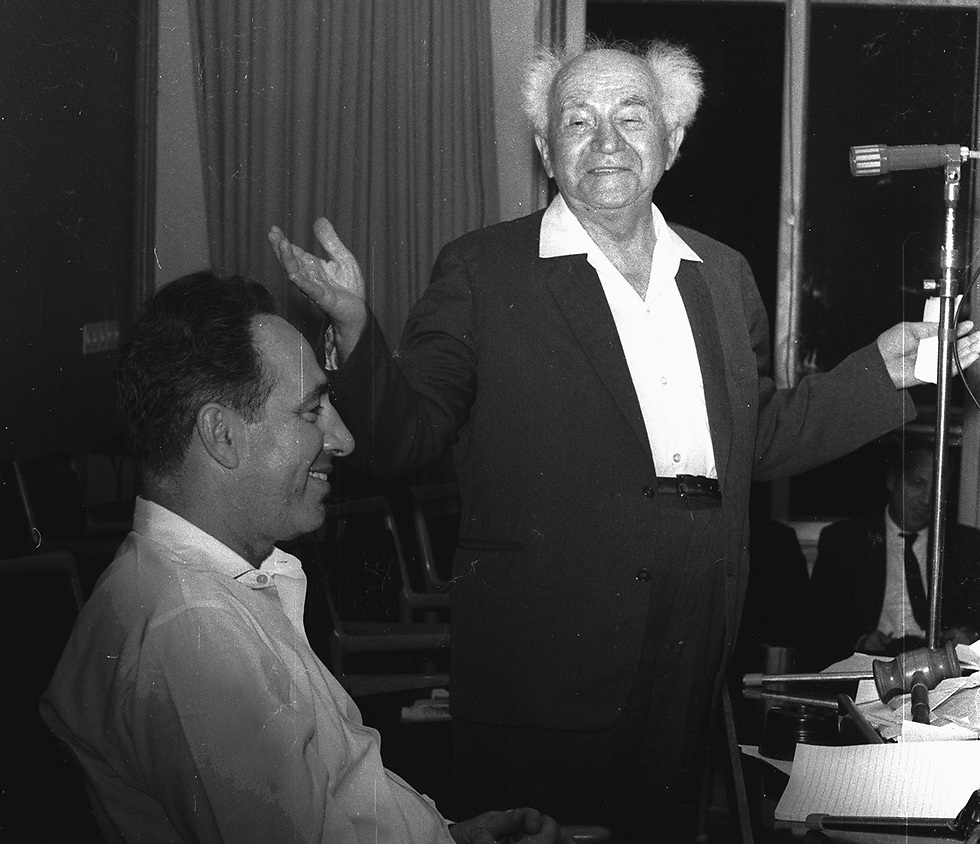

"Early on, I didn't have a lot of connections in France. But I was a member of a socialist party, and I met several socialists thanks to my ties in the Socialist International (SI). The head of the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO) party at the time was Guy Mollet. I met him at the Socialist International on the eve of the 1955 elections in France, and we became friends.

"Later, he was elected prime minister. But despite the fact I had some very close friends in France, there were disagreements in the country about supporting Israel. There was no precedent for that in the world, for one country to allow another country to build a reactor without a commitment to international supervision. This was the first time something like this was happening. So they gave us a reactor, but several parts were missing. We negotiated with the French Committee for the Military Applications of Atomic Energy, as well as the French defense minister, Prime Minister Guy Mollet, and National Defense Minister Bourgès (Maurice Bourgès-Maunoury). There were a lot of arguments and negotiations.

"And there was one dramatic night in 1957. We didn't have a signed agreement. The French government was on the verge of collapse. Mollet had resigned. But before he resigned, Bourgès asked me to ask him (Mollet) that he (Bourgès) would be his replacement. That's how close our relationship was. So I talked to Mollet and he agreed. Now, when Bourgès was appointed prime minister, I was in a position to write him a note, so I did. He stepped out of the meeting. I told him: 'Listen, the meeting is about to end and we don't have your signature as the national defense minister. Sign it as the national defense minister.' But he wasn't (the national defense minister) at the time, so he signed it with the previous day's date. Meaning, he forged the date and signed it."

What happened with the intelligence plane?

"One day, a British jet plane flew over Cyprus. Our intelligence establishment thought the plane was looking for our nuclear reactor. They went to Ben-Gurion and told him: Our big secret has been found out. I was in Africa at the time, and I was called back. It was Passover eve of 1957. I arrived in Sde Boker (where Ben-Gurion lived) with Golda (Meir) and the Mossad director at the time. Golda and the Mossad director said he had to go to America, reveal the big secret to them, and tell them we were stopping (the construction)—otherwise the world powers would give us hell. I said that even if the plane did fly by, it didn't see anything. What could it see? Bulldozers? I told them we can't reveal something like that (to the Americans) without first talking to the French. It was top secret, and if we wanted to reveal that secret we had to consult with the French. Ben-Gurion accepted my position. It was a moment of crisis.

"By the way, it was a miracle the reactor was kept a secret, because thousands of people were working on it. Today, we would have done everything to hide it from the media, and it's doubtful we would have succeeded. I always say: there are things the people don't want to know. The people don't want to know how many tanks the IDF has. The people agree that secrets must be kept to protect the nation. We don't have to tell them everything."

'We're experts on the past, but there's no expert on the future'

Why don't you make your position known on recent diplomatic and political issues?

"Because it's not the right time at this point. And I don't think it'll help anything. The problem is that the ears are closed. No one listens to anything these days."

What would you have wanted to say?

"I'd like us to go back to being a nation that is both democratic and Jewish. If we say that 'a good Arab is a dead Arab,' then that's not democracy, and it's saddening. The Torah explicitly says: 'Love ye therefore the stranger; for ye were strangers in the land of Egypt.' We must not have discrimination. It goes against the Torah."

What happened to us? How did we get to this place?

"I'm less interested in analyzing the problem and more interested in fixing it. Those who make racist comments disgrace the State of Israel. I can't accept it. No one needs to accept it. It's not to our benefit, when people talk against gays and Israeli Arabs. All Arabs must be killed? We do have the rule of law here. 'Zion shall be redeemed through justice.' Begin also said that 'There are judges in Jerusalem.' So why aren't we protecting the justice system more? A Jew was once almost killed because he was mistaken for an Arab. That was absurd, this argument. Just as I hurt when someone tries to kill a Jew, I hurt when a Jew tries to kill someone because he's an Arab."

Do you still think peace is possible?

"For us, the Arab world remains something static—made of half Shiite and half Sunni and that's it. People don't understand there is a young generation and that a revolution is underway there. Out of 400 million Arabs, more than half of them are under 25. That's something different altogether. We're experts on the past, but there's no expert on the future. The future needs a vision, and we lack that today. But the thing Israel lacks most today is peace. The fact there is no ongoing peace process at the moment is the main thing that bothers me."

Politics get a bad name.

"Because there's a kind of smugness today. When we were under British rule, and there was a high commissioner, a representative of the king, he would sign his letters: 'your obedient servant.' It was a bit for show, but it was a nice show. I miss this tone in leaders. And I miss leaders who take action. There's a difference between words and actions. There are those who say: 'If you said it, you did it.' It's been a characteristic of a lot of governments, including the current one. And I thought, and still do: If you say you'll do something but don't do it, it isn't worth anything."