“Zionists, come to your senses,” said Kursat Mican, a local leader of the Alperen Hearths group that spearheaded the protest. “If you prevent our freedom of worship there then we will prevent your freedom of worship here.”

Ivo Molinas, the editor of Turkey’s Jewish newspaper Shalom, summed up the feeling of many Turkish Jews with a post on Twitter. “I am a Turkish citizen,” he wrote. “Why are you protesting in front of my place of worship?”

No one was injured in Thursday’s attack, which was later followed by a second protest by an Islamist group outside Istanbul’s Ahrida Synagogue. But the demonstrations served as a reminder of the challenges confronting Turkey’s small Jewish community, which not only contends with widespread anti-Semitism but also finds itself caught in the crossfire any time Israel faces criticism.

Turkey has a complex relationship with its small Jewish minority, which today numbers around 17,000 people. Officials talk proudly of the fact that Ottoman Sultans welcomed Jews expelled from Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries, and of the efforts made by Turkish diplomats to save Jews from the Nazis. But anti-Semitic tropes are deeply engrained and widespread in the media, popular culture and in political rhetoric.

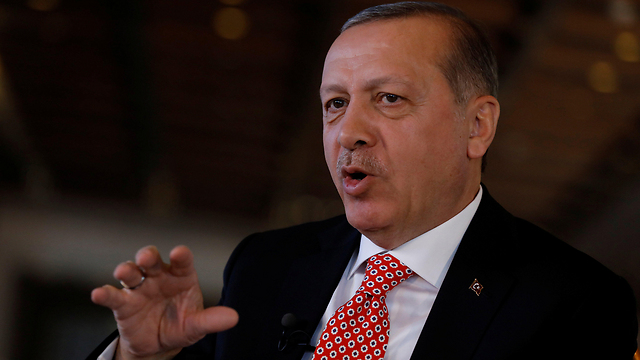

A new historical drama, Payitaht, aired on the state broadcaster’s flagship entertainment channel, depicted a plan to kill the Ottoman Sultan by plotters who exchange coins imprinted with the Star of David. Hitler’s Mein Kampf can often be found on sale in mainstream bookshops and supermarkets. Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan himself once used the term “spawn of Israel” to insult a protester after a mining disaster in 2014. His ministers, advisors and officials have repeatedly been criticized for using anti-Jewish language and conspiracy theories when attacking critics or seeking to explain economic or political problems.

The phenomenon is not confined to Erdogan and his Justice and Development Party (AKP). Anti-Semitic diatribes are also prevalent in anti-imperialist and left-wing nationalist circles, as well as their right-wing and Islamist counterparts.

However, Erdogan, who casts himself as a leader of the Muslim world, has taken a tougher stance on Israel than some of his predecessors.

Although Turkey and Israel announced a rapprochement last year after a six-year diplomatic freeze, Erdogan has made clear that he will continue to censure Israeli policies towards the Palestinians. Following the decision to place metal detectors—since removed—at the Al-Asqa mosque after the killing of two Arab-Israeli policeman by Muslim gunmen, Erdogan issued a series of harsh condemnations.

Turkey’s Jewish citizens defend the right of politicians and the public to criticize the state of Israel. The problem, they say, is that ordinary Jews face blowback. “The intensification of the conflict between Israel and Palestinian always extends to the Turkish Jewish community,” said Karel Valansi, a columnist at the news portal T24 and the Jewish newspaper Shalom. “There is no clear distinction in the minds of many in Turkey between Israel and Jews.”

Turkish officials have made efforts to publicly support and promote the Jewish community in recent years. In 2015, a Hanukkah celebration was held in public in Istanbul for the first time in several decades. The same year, one of Turkey’s deputy prime minister’s attended the re-opening of Edirne Synagogue, near the border with Bulgaria, which was given a $2.5 million renovation after languishing for many decades in a state of disrepair.

But Aykan Erdemir, a former member of parliament with the opposition Republican People’s Party (CHP) now based at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies in Washington, said that life has become more difficult for Turkey’s minority groups in the wake of last year’s attempted coup. Erdogan portrays the failed putsch, which left 250 dead, as a plot by foreign and domestic powers conspiring to destroy the country—tapping into deeply-ingrained national fears about threats to the Turkish state.

“Turkey was a challenging place for religious minorities even before the coup,” said Erdemir. “Things, however, have gone from bad to worse within the last year. Turkey’s government-controlled media systematically demonize minorities, presenting them as fifth columns.”

Erdogan condemned the attacks on Istanbul synagogues, saying that it was “a big mistake” to target a place of worship. “We have no issues with the houses of worship of Christians or Jews,” he said. Opposition leaders also denounced the attacks.

Despite the protests, Turkish Jews say that physical assaults against them have been rare in recent years and that the government has taken warnings of Islamic State attacks very seriously. Some say they feel safer in Turkey than they would in Europe.

But most agree that Turkey must do more to tackle the hate speech that Jews encounter in public debate, the media and on social networks. And they would like to see greater awareness of the fact that Jews are separate from Israel, so that they do not have to brace for a backlash each time it hits the headlines.

Selin Nasi, a columnist for the Turkish newspapers Shalom and Hurriyet Daily News, said that Turkey’s Jews want to feel accepted by politicians and by society. “They want to be treated as equal citizens,” she said. “They don’t want to be perceived as enemies. They love their country. They don’t want to come to the fore each time a crisis breaks out and be held responsible for what Israel is doing.”

Reprinted with permission from The Media Line.