Current Lord Balfour: Everyone knew Jews needed a home

As Britain prepares to celebrate 100th anniversary of declaration supporting establishment of Jewish national home in Palestine, Roderick Balfour says his great-great-uncle Arthur James Balfour would have been incredibly proud of what he and his generation set in motion, but would have been disheartened about ‘hopeless situation’ between Palestinians and Israelis.

But Lord Roddy Balfour never truly understood what his last name meant to the Jews and the importance of his relative, Lord Arthur James Balfour, until that rainy evening in the mid 1960s, when he got into a taxi in London with a rather unusual baggage.

“I was coming home from Eton one evening, and I’d collected a picture from my aunt. It was the days of the old cabs where you always put your luggage in an open place next door to the driver. I was on my way back to Paris and I had my school trunk in the car. So this driver spotted the name Balfour on the luggage tag and asked me was I anything to do with Arthur James Balfour. I said, ‘Yes, I’m his great great nephew.’ And he suddenly broke into sort of Hebrew song and said, ‘This is incredible. This is the eve of the Passover, and this is my last fare and then I’m going back to the east End of London to celebrate Passover with my family. When I tell them I’ve had a relation of Arthur Balfour’s in the car, they’re going to just be amazed.’

“I was so taken with his singing and was very moved, as I’d never come across this before. And in getting out and thanking him and him getting out of the car and embracing me, I’d left the picture in the back of the cab. My father was going to kill me because it was a family picture. So I rang the lost property office and went up to Islington, and there was this picture wrapped in brown paper with string, saying Balfour on it, which I hadn’t done. And this guy, who was on his way back for the eve of the Passover, had taken the trouble to get this Balfour picture to the lost property office and beautifully wrapped. Amazing. That was my first interaction with somebody Jewish who explained to me the importance of the declaration.”

With a surname that is part of Israel’s history textbooks, and an aristocratic estate that looks like it was taken out of a fairytale, Lord Roderick Francis Arthur Balfour is the direct successor of Arthur Balfour, the British politician who was one of the first leaders in the world to support a national home for the Jews in the Land of Israel.

Arthur Balfour was born in 1848. When he served as prime minister from 1902 to 1905, Britain was the first country to try to help the Jews find a homeland. Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain proposed to Theodor Herzl to provide a portion of British East Africa to the Jewish people as a homeland (the Uganda Scheme).

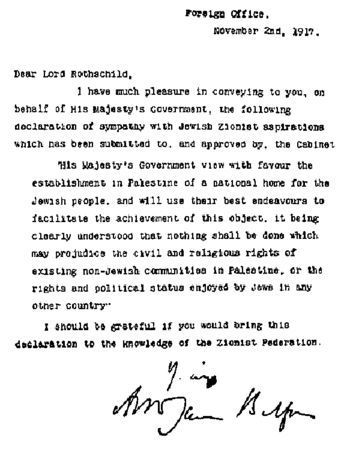

On November 2, 1917, a year after being appointed foreign secretary, Balfour wrote a letter to Lord Walter Rothschild, one of the leaders of the British Jewish community, which later became known as the Balfour Declaration. The letter was written after Zionist leaders Dr. Chaim, Weizmann and Nahum Sokolow asked the British government to acknowledge the Jews’ right to immigrate to the Land of Israel and recognize the Zionist Movement’s institutions there.

A rare show of support for the Zionist idea by a foreign leader, the declaration is seen as an important event in the history of the Jewish people. The Balfour Declaration was a ray of light in the dark history of Jews in the first half of the 20th century, following persecutions and pogroms and before the Holocaust which nearly eliminated the Jewish people. It was compared in the Jewish world to the Cyrus Charter, which marked the Jewish people’s return to their land after the First Temple’s destruction.

‘He was always known as Uncle’

Arthur Balfour inherited the title of Lord from his father. He himself was childless, however, so the title was passed on to his brother Gerald and his sons. The current Lord Balfour is Roddy, his brother’s great grandson, who not only holds the official title but is also considered Arthur’s successor.

His luxurious home, in the county of Sussex, a 90-minute drive from London, is decorated with many items that used to belong to his famous relative, including an original wax seal of Queen Victoria and a ring with the official family symbol imprinted on it. The only thing that’s missing, Balfour says, is a Torah scroll that Arthur received when he laid the cornerstone for the Hebrew University on Mount Scopus in Jerusalem and which went missing over the years.

What did you know about Arthur?

“I knew primarily that he got through a huge fortune, running this house, financing all his family, very poor investing. He was a philosopher, he was a man of letters, he was a very thoughtful politician. They always said the problem with Arthur is he’s weak in the House of Commons because when he’s asked questions, he says: ‘On the one hand this, and on the other hand that.’

“He was always known as Nuncy in the family, like Uncle. Obviously, his memory was very revered within the family, other than the fact that he got through so much money. When he inherited it in the mid 19th century, I think he was one of the two or three richest bachelors in Britain.”

Arthur Balfour never married, but the family knew about his liaison with Lady Elcho, who was married to his good friend Lord Elcho. When he died, he left houses, land and money to his brother and to his nephews and nieces. Some of this inheritance reached Roddy Balfour as well, although he stresses that he belongs to the “poor,” political side of the family.

The family’s political branch produced another prime minister (Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil), two parliament members and a member of the House of Lords (the upper house of the British Parliament). But there’s no need to feel sorry for Roddy Balfour: The palace of the Duke of Norfolk is not far from his house, and the duke just happens to be the brother of Tessa, Balfour’s wife in the past 46 years. Balfour’s four daughters stand to receive an impressive inheritance one day. One problem has yet to be solved though: The hereditary title is only passed down to sons. “He tried to change it,” his driver explained to me, “but was unsuccessful.”

A magnificent portrait of Arthur Balfour, from his days as prime minister, hangs alongside original works of art in the spacious parlor. It wasn’t the political status which generated the subdued wealth reflected from every corner, which is typical of families of old money. The Balfour family became very rich when India was a British colony. One of the family members, James Balfour, made his fortune in India, where he developed engineering infrastrctures for the British empire. He returned to Scotland, where the family originally came from, and built luxurious estates which the family still owns to this very day.

“Almost everything you see around you belongs to the family, through an inheritance or marriage,” Balfour’s elderly driver tells me as we make our way to the family estate, on the top of a green hill.

Working for the Rothschild family

Roddy Balfour was born in London on the exact same year as the State of Israel. His father, Eustace, was in charge of the business operations of a large British engineering company in France, and Roderick was brought up abroad.

“I was brought up in Brazil at first and then in France,” he says. “I came to school in England. But in the summer holidays we’d go and stay with all our cousins in Scotland and see these big houses, and therefore one was conscious of the whole family history because one was staying in these huge houses. In those days, Arthur hadn’t been dead for more than 30 years or something, so one was conscious that he’d been prime minister and that this was a big family who had achieved something in life. It wasn’t something we thought about every day. We led a very suburban life in the suburbs of Paris.”

But his surname dictated his path. He studied at Eton College, a prestigious boarding school for boys which has educated members of the royal family and boys who went on to become Britain’s prime ministers.

“It’s a select club,” he says. “We had marvelous tutors. I think it’s always attracted good people, good masters. In the old days, you got in there in a way because you were your father’s son. But you still got a very good education, and the idea was that you would end up in Oxford or Cambridge. In those days, it was much easier to progress. It was self-perpetuating, because you had big families who ran industries—whether it was brewing, whether it was banking—who had been to Eton, and they understood the education people had had at Eton, so it was natural for them to want to employ people who’d had that training.”

Balfour works as a tax consultant for wealthy people and large companies trying to avoid double taxation in their worldwide businesses. He experienced a sort of closure in one of his first jobs, working for the Rothschild family. In the 1980s he also worked for Nikanor, a company owned by Israeli billionaire Beny Steinmetz, who was recently detained over suspected bribery and fraud.

Twenty-five years ago, Roddy Balfour opened the newspaper one day and saw that the Anglo-Israel Association had had a dinner for the 75th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration. “It had all the people who attended, and there was no Balfour there!” he says. “I thought that was strange, so I wrote to the Association and said: ‘What’s going on? Do you know any of the Balfours?’ And they said no. So I said, ‘I’d be very pleased to get involved. I feel we should reconnect, the Balfour family, with the declaration.’ So I’ve been involved in the Anglo-Israel Association in London for that 25 years.”

The famous declaration is essentially a letter which was written following many debates in the British Cabinet and after many drafts. The original wording included the following sentence: “His Majesty's Government accepts the principle of recognizing Palestine as the National Home of the Jewish people.” The final version states: “His Majesty's government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people… it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.” The last sentenced sparked a row, which we will get back to later.

"All that generation were very supportive (of the idea of a national home for the Jewish people in Palestine),” says Balfour, “apart from (Edwin) Montagu, the Jew in the cabinet who opposed the declaration and thought that it would not help British Jewry.

“We all knew that the Jews needed a home because of persecution, so it wasn’t something to debate, it was just a fact of life. Later on, obviously, one realized what sort of amount of lobbying and battling needed to go on to get the declaration produced.

“You have to look at Palestine as it was then. It was a desert, a mosquito-infested swamp. The Palestinians on the whole were looking after their goats and sheep. And so, after all, all of us who are of the Abrahamic faith, whether you’re Christian or Muslim, were all brought up to believe in Moses and Abraham and then later on Jerusalem and Bethlehem. So the Holy Land is absolutely ingrained in the Old Testament, which we all read. All these things were so natural, so to put it down in the Holy Land didn’t arouse a lot of discussion because that was the land of the Jews. That was what everybody thought. Nobody really thought about the Arabs as Muslims in those days with their separate religion.

“I don’t know what arguments there were about Jerusalem, the Dome of the Rock and all that sort of stuff those years, and there was obviously a bit of resistance by the indigenous Palestinians. But when you look at it, there was just a huge uninhabited land basically. When these guys did the declaration, they had no possible incline that there would be this sort of invasion and birth explosion in the place, and they never knew Hitler was coming along and then the Holocaust.”

The declaration was adopted after weeks of debates.

"It was a government thing. There was a big debate about where it should be in. There was the idea that it could be in Uganda originally. We were a primary recipient of victims of the pogroms here. They came to England, and then some of them crossed over to Liverpool, went off to the US.”

So that was one of the reasons for this declaration, for this support for finding a solution for the Jews.

“Yeah. I mean, we complain about the Muslims today arriving in their burqas or their hijabs, and not speaking English. But it’s slightly different. They’ve come here voluntarily, an awful lot of them. But the people from the pogroms arrived from the shtetls speaking Yiddish. They had no idea what English was, so they suddenly arrived on boats in England, unable to communicate with different religious habits, not wanting to do anything on a Saturday and just looking different. Exactly the same problem of integration. And I think they just made a very good case for the Holy Land, and there wasn’t any real reason to resist it. This was an empty barren land, and the Israelis have done so much. All the kibbutz and draining the swamp and growing everything. Palestinians could have done that for themselves, but they’ve never chosen to do so.”

‘You keep what you conquer’

Roddy Balfour is very supportive of the declaration and of the State of Israel, and he doesn’t hide it.“We just knew that Jews live in Israel, it was just axiomatic. There was no debate about whether they should. Then of course we had the Six-Day War and I worked for the Herald Tribune in Paris at the time, and France was very pro-Israeli. There were massive demonstrations in Paris in favor of Israel, so I was very conscious then of this as well.

“Obviously we were suddenly conscious of all these options when you had the Six-day War and Egypt trying to be opportunistic to wipe out Israel, and Israel just smashed them to pieces and took over the occupied territories, Sinai and the Golan and everything. And that to us seemed, you know, if you win—that’s what you do. You keep what you conquer, especially if it’s going to increase your security.

“It’s only really in the last 20 years where we’ve gone from nobody talking about the declaration to often saying to me, ‘Oh, yeah, of course it’s your Balfour Declaration that’s caused all the problems in the Middle East,’ to which I say, you can’t really say that, because the world was a very different place when it was made, when it was posted to Lord Rothschild.

“The Palestinian population has expanded, and one of the problems is that the Palestinians are not self-sufficient. They lived in the same land, they had the same opportunity, they can cultivate stuff, they could do whatever it is, but they don’t seem to want to help themselves and I don’t think they have any more right to Palestine than the Jews do, all the Abrahamic faiths. But they just do think of it in a different manner. I think it is really sad that they can’t sort of get their economy together and don’t seem to be politically motivated to do so. It’s almost a sort of totalitarian idea: We will live in misery because we can then blame all our misery on Israel.

A lot of people blame the lack of leadership on the Palestinian side with this entire situation.

“Well, there’s leadership, but it’s leadership of the wrong sort. It’s wanting to subjugate. I think it’s just very sad that we can’t get these people to all work together in their respective territories to have economic wellbeing. You know, the Israelis don’t want to rub out all the Muslims, but the Muslims do want to rub out the Israelis.”

If Arthur Balfour were alive today and visited Israel, what would he think?

"I think the fact that we’ve had these terrible events, the Jewish persecution and the Holocaust, the genocide, and it offered a way if you could escape for somewhere to go and live with your own kind, I think it was a great thing to have done. I suspect Arthur and all that generation would be incredibly proud had they known what Hitler was going to do to the Jews, they would have been even more pleased with what they set in motion. But they wouldn’t be pleased about the hopeless situation between the Palestinians and the Israelis. The central tenet in the thing about the indigenous population has rather gone out of the window in just increasing the settlements and evicting Palestinians. Not good politics, you know, for the rest of the world.”

Roddy Balfour has never actually seen the original declaration, which is in the British Library. “I’m ashamed to say I can never remember the wording of it,” he says. “I should know it by heart, but I don’t.”

In the coming months, however, he will be required to delve into its details repeatedly, when he takes part in many events in Britain marking the declaration’s 100th anniversary. The events will also be used to strengthen the already warm relations between Israel and Britain. British Prime Minister Theresa May, perhaps the most pro-Israel person who has ever lived on 10 Downing Street, is expected to deliver a special speech. Last December, in her first speech to Conservative Friends of Israel as prime minister, she stated that the Balfour Declaration had been "one of the most important letters in history."

The Palestinians, of course, see no cause for celebration. Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas argued in the past year that the Balfour Declaration ultimately led to the Palestinian Nakba and urged the British government to apologize to his people. “We ask Great Britain to draw the necessary lessons and to bear its historic, legal, political, material and moral responsibility for the consequences of this declaration, including an apology to the Palestinian people for the catastrophes, misery and injustice this declaration created and to act to rectify these disasters and remedy its consequences, including by the recognition of the state of Palestine,” he told the UN General Assembly in 2016. “This is the least Great Britain can do.”

The British government refused to apologize. Balfour agrees, explaining the declaration was issued out of good intentions and there is no reason to apologize for the fact that reality did not turn out the way the Palestinians wanted it to.

At the end of the interview, he stands in front of his great-great uncle’s portrait, failing to hide his admiration. And then he remembers something. The first time he visited Israel, he came to Tel Aviv and discovered that the street named after General Allenby is longer than Balfour Street. “I think it should be the other way around,” he says.