Submarine affair's secrets are coming to the surface

Secret meetings in effort to prevent the suspension of the submarine deal, the changes Israel requested that could indicate capability to launch nuclear missiles from the submarines, and Ya'alon's claims Netanyahu pressed him on the patrol boats deal. Yedioth and DIE ZEIT uncover more details of the affair that complicated Israeli-German ties.

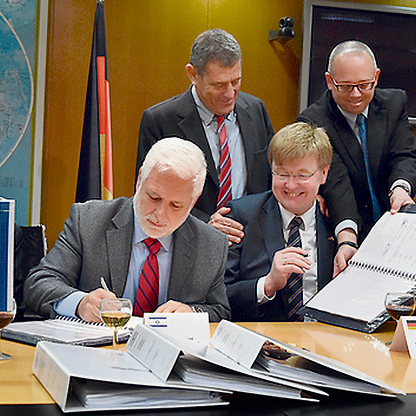

Miki Ganor, the man whose scheming is currently making life difficult for governments in both Berlin and Jerusalem, is in a light-hearted mood. He is standing between an Israeli government official and a German executive from ThyssenKrupp. The executive is smiling as Ganor sets his hand jovially on the man's shoulder—and then the contract on the delivery of German warships to Israel is signed.

This scene was documented in a photo taken in May 2015. Ganor, ThyssenKrupp's representative in Israel, is the man in the shadows, the orchestrator of an arms deal that has far-reaching, international importance. That is the message of the photo.

Today, the governments in both Jerusalem and Berlin wish that Ganor, now 66, had never managed to find his way into that photo. Since early summer, the lobbyist has been in special detention because he is suspected of having paid large bribes to high-ranking government officials in Tel Aviv and Jerusalem to ensure that the arms deal went ahead, including to the former head of the Navy. A cousin of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu is also among those suspected of wrongdoing. More than half a dozen people have already spent some time in detention.

The deal in question involves the purchase of German warships and submarines, more than 2 billion euros and Israel's security. The affair leads directly to the heart of the German-Israeli relationship, one that is a key to Germany's understanding of its role in the world, and is weighing heavy on the relationship between the two countries.

The case doesn't just put Netanyahu—whose role in the affair isn't entirely clear—in a tight spot. It also plunges the German government into a dilemma. Berlin subsidized the arms export deals to the tune of 700 million euros, but can the German government allow an arms deal to go through despite the apparent payment of large bribes? How does the Chancellery intend to explain that German taxpayer money ended up in the pockets of people close to Netanyahu? How much bribery, in other words, can the German-Israeli relationship withstand?

The relationship between Israel—a country that provided a home to Holocaust survivors—and Germany—the country of National-Socialist perpetrators—has always been a special one, and that also extends to arms exports.

Israel's security is "part of Germany's raison d'être," German Chancellor Angela Merkel, of the center-right Christian Democrats, promised in an emotional speech to Israeli parliament in March 2008. "Israel's security is nonnegotiable for me as chancellor," Merkel said.

Her predecessor Gerhard Schröder, of the center-left Social Democrats (SPD), had a similar view. With respect to arms exports, he said, "I want to state very clearly: Israel will get what it needs for the preservation of its security."

This unconditional solidarity has been tested occasionally by political differences—on settlement policy, for example, or on the relationship between Israel and the Palestinians. But the delivery of heavy weaponry continued apace, no matter how deep the grievances between the two governments were. The Chancellery, however, has long been eager to keep the arms deliveries out of the public eye to the degree possible—for fear that voters would be opposed to exporting German weapons to one of the most volatile regions of the world.

That, in fact, is the greatest danger presented by the current corruption affair: it could dissolve the quiet consensus of the Berlin elite and call into question Germany's unconditional solidarity with Israel.

Because Germany isn't just delivering conventional military supplies, but water-born, precision weapons that would play a decisive role in the case of nuclear war: Dolphin-class submarines, produced in the Howaldtswerke-Deutsche Werft in Kiel, a shipyard that belongs to ThyssenKrupp, which is listed on Germany's DAX blue chip stock index.

The vessels aren't just extremely quiet and agile, allowing them to operate in the shallows of Mediterranean coastal waters and of the Persian Gulf. They also carry an open secret: The Israelis arm them with nuclear weapons.

For Israel, the submarines serve as a kind of life-insurance policy. They guarantee a so-called second-strike capability, the ability to strike back following a nuclear attack or a devastating conventional attack. The warships "guarantee the enemy doesn't feel tempted to launch a preventative strike with nonconventional weapons thinking it would go unpunished," says Israeli Admiral Avraham Bozer. And the former commander of the Israeli Navy, Ami Ayalon, says: "For our country, the purchase of the submarines was the most important strategic decision." No other country would have been as obliging as Germany when it comes to this delicate issue.

On January 30, 1991, shortly after the start of the Gulf War, the German government, then under the leadership of Chancellor Helmut Kohl, promised the delivery of the first two submarines, which were paid for entirely by Germany. The contract for vessel number three was signed in early 1995. Schröder's government, a coalition of the SPD and Green Party, authorized the export of Dolphins number four and five in 2005. Officially, the Chancellery still claims ignorance regarding the nuclear modifications undertaken by Israel.

The fact the deals rarely hit the headlines is also due to Israeli national hero Shaike Bareket, a highly decorated veteran of the Israel Air Force. He operated as a representative for ThyssenKrupp starting in 1991 and commuted regularly between the two countries.

The rules of the game change

In a quiet side street in a Tel Aviv suburb, a modern villa lies hidden behind a wall that glows violet with bougainvillea. Bareket, 82, opens the door and invites his guest inside. An impish smile spreads across his wrinkled, friendly face. Bareket was part of the submarine project from the very beginning.

Sometimes he could be found poking around the shipyard in Kiel, along with the engineers from Germany and Israel. At other times, he would meet with the head of ThyssenKrupp Marine Systems at the time, Walter Freitag, in Tel Aviv. Bareket lived well from the commissions he earned from the company. And ThyssenKrupp likewise benefited from Bareket's contacts.

But in 2009, the rules of the game suddenly changed. Freitag traveled to Tel Aviv for negotiations on additional submarines, and Bareket picked him up at the airport and escorted him to a meeting at the Israeli Defense Ministry. But an assistant to the head of the Navy at the time, a vice admiral, intercepted them in the parking lot. The assistant pointed at Bareket and said, according to Bareket's recollection of the incident: "I don't want Bareket to take part in the meeting."

Freitag responded, Bareket recalls, by saying that he wasn't going anywhere without Bareket. In response, the man said: "Then there won't be a meeting with the vice admiral."

When recounting the episode today, Bareket shrugs off the painful humiliation with a smile. "At that moment, we were so embarrassed by the situation that I told Mr. Freitag he should go to the meeting without me."

According to Bareket, the Israelis drove Freitag to Jerusalem following the meeting with the vice admiral for another one, this time with the finance minister at the time.

That evening, at a gala dinner in Tel Aviv, Miki Ganor was a surprise guest at the table. At the dinner, Bareket learned what had been discussed earlier in the day: Namely that if ThyssenKrupp wished to continue doing business with Israel, the company would have to accept Ganor instead of Bareket as its chief lobbyist in the country.

ThyssenKrupp has only sparse records pertaining to the sudden lobbyist change in 2009—and perhaps the company didn't want to dig too deep into the reason for the change. Freitag had a reputation for writing only very few emails and hardly any memos. In the company files, the change from one lobbyist to the other is explained by a brief reference to Bareket's age, who was over 70 at the time. Company records do not, however, indicate what qualified Ganor to work as a lobbyist on behalf of one of Germany's largest companies. While he had served on an Israeli warship as a young man, he went on to become a trade representative for an Austrian banking association and for a real estate firm.

Until that moment, Ganor had brokered bank loans and property deals, but now he was suddenly in the business of brokering the sale of nuclear-capable submarines in the Middle East.

In March 2012, government representatives from the two countries signed a contract for the export of the sixth submarine in Berlin. The German government subsidized the deal to the tune of 135 million euros.

And Ganor was able to initiate additional arms deals. At around the same time as the contract for the sixth submarine was signed, the Israeli government presented a new idea: Would the German government also approve of the purchase of four corvettes from Germany and participate in the financing?

Ever since Israel began pumping natural gas out of the Mediterranean Sea floor, the country has been able to do without natural gas imports. But the infrastructure required to do so, including drilling platforms and transport vessels, is vulnerable and must be defended against possible attacks by Hezbollah and Hamas. That is why it needed the corvettes, which are more robust than any warship Israel has ever possessed.

From Netanyahu's perspective, Germany was the perfect partner for such a deal. German defense technology is expensive, but has an excellent reputation. And the German government had spent billions subsidizing Israel's purchase of the first six submarines. Why wouldn't it do the same for the corvettes? Plus, if the contract were awarded to ThyssenKrupp, Ganor would receive a huge commission for facilitating the deal.

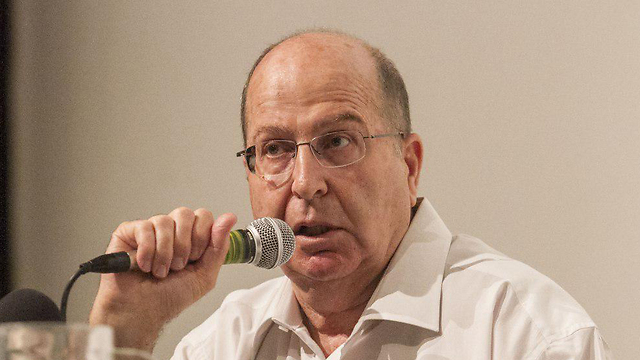

At the end of 2013, the Israeli Security Cabinet, under Netanyahu's leadership, agreed to award the contract to ThyssenKrupp without a public tender—despite vehement protests from then-Defense Minister Moshe Yaalon, who was concerned that without competition, ThyssenKrupp would demand inflated prices.

But this time, Germany didn't respond as the Israelis had expected. Instead of rubberstamping the deal, Merkel's foreign policy adviser, Christoph Heusgen, signaled to Netanyahu's people that the Chancellery would make the corvette subsidies contingent on two demands: a change in the Israeli government's settlement policies and increased dedication to the Middle East peace process.

Netanyahu becomes personally involved

The move was far from uncontroversial within the German government. Making such demands could be interpreted as a step back from Merkel's promise regarding Germany's raison d'être. Furthermore, Schröder's pledge that the Israelis would always get what they needed would no longer be unconditional.

For the Israelis, the message from Berlin was clear, and they reacted in their own way. In May 2014, the Defense Ministry decided to officially put the contract out to tender after all, despite its original intention to award it to ThyssenKrupp. The tendering procedure, says an Israeli who participated in the process, was an attempt "to put the German government under pressure." In an internal email, a high-ranking Israeli defense official exulted: "The Germans and their Israeli representative don't like the idea of an international tender at all."

Arms manufacturers from several different countries took part in the tender, including a South Korean consortium under the leadership of Hyundai, which offered to build the ships for 96 million euros per vessel, much cheaper than ThyssenKrupp. Would the contract not go to Germany after all?

Ganor, who the Israeli official had been referring to in the internal email, must have panicked. He suddenly found himself faced with the prospect of losing out on a multimillion-euro commission.

Luckily for Ganor, though, he had developed an alliance for the corvette deal with a man who had excellent contacts with the Israeli prime minister: David Shimron, a well-respected lawyer, who isn't just Netanyahu's personal legal representative and occasional foreign policy adviser, but also his cousin.

Shimron and Ganor were in close contact since the corvette deal began taking shape in 2012. In the negotiations, Shimron introduced himself as Ganor's legal adviser, but he sometimes seemed to change roles. In the files pertaining to the corvette deal, there are at least four instances in which Shimron semmed to play an active role, such as during an early 2015 meeting, which focused on so-called offset deals ThyssenKrupp would commit to as part of the corvette deal. It was never easy for ThyssenKrupp, nor for the German or Israeli government officials, to determine what role Shimron was playing at any given time—whether as Ganor's adviser, as confidant to the prime minister or as his cousin.

The excellent contacts paid off. Shimron leaned on several different public officials in Israel. The files reveal, for example, that he called the Defense Ministry's legal adviser to insist that the public tender be stopped.

When that didn't bear fruit, though, Netanyahu became personally involved. "The prime minister himself came to me and said, why is there a tender?" former Defense Minister Yaalon told a confidant of his a few months ago. He "asked me to cancel it." The pressure to halt the bidding process at the time "went through all kinds of channels," Yaalon says.

Following months of pressure from Netanyahu's advisers, the Chancellery indicated its willingness to subsidize the export of the corvettes after all, even without Israeli concessions. And in October 2014, the Israeli Security Cabinet put an end to the tender.

The contract was signed on the sidelines of a May 2015 visit to Tel Aviv by German Defense Minister Ursula von der Leyen. The Israeli government was to pay 430 million euros for the four corvettes, with the German government having agreed to assume 115 million euros of that total. The ships are currently under construction.

Ganor looked extremely pleased on the day of the signing. ThyssenKrupp wired a total of 10.4 million euros to the accounts of three of his companies and his contract stipulates he will receive an additional 10 million. The deal turned him into a multimillionaire, even after the bribe money investigators believe Ganor handed out is subtracted.

But the corvette deal was supposed to be just the prelude to a deal that would have even larger implications: the order of three additional Dolphin-class submarines from Germany—the seventh, eighth and ninth such vessels, with a total order volume of around 2 billion euros. But again, the deal descended into scandal because then-Defense Minister Yaalon refused to play along. Again, it is thought that corruption and bribes were the result. "It is clear to me there is a stench about the issue of the German ships and shipyard," Yaalon says. With respect to the submarines or the corvettes? "Both," he says.

Yaalon receives his guests on the fourth floor of an office building in northern Tel Aviv. Behind the glass door, a security guard sits with a headpiece in his ear. It's from this office that Yaalon directs his new political initiative, "Different Leadership." Wearing a short-sleeved shirt, he orders a coffee and starts talking.

There was little interest in a sixth submarine, the deal for which was signed in 2012, from the Israeli Navy or from the Defense Ministry, Yaalon says. It was Netanyahu himself, Yaalon says, who pushed it through. The position of the Israeli government had long been that Israel only needed five submarines, Yaalon says. At some point the old vessels will need to be replaced, he says, but not yet. "The first one will not be old enough." Yaalon leans back and crosses his arms. "There was no need for a sixth" submarine, he says, adding that he told Netanyahu as much at the time.

But the prime minister didn't listen to his defense minister. On the contrary, he pushed the deal forward behind his back. In October 2015, Netanyahu visited Berlin and requested that the chancellor approve the delivery of three additional submarines. Merkel signaled her fundamental acquiescence.

Yaalon claims Netanyahu had even wanted to expand the deal and request two additional ships for defense against enemy submarines. "There was no discussion of this issue between the prime minister and me. I did not hold any discussion on the topic in any forum. Nothing happened in the Defense Ministry or in the Navy or in the IDF," he says. "And no one ever heard of any plan to buy anti-submarine ships," Yaalon adds. The former minister gets so worked up during the conversation that he knocks over his coffee. "It was all out of the blue," he says.

'Ganor wasn't talking, he was singing'

Did the Israeli leader force through a multibillion-euro defense deal against the advice of his defense minister to generate handsome profits for everyone involved? For the former head of the Navy, for example, who is now facing potential prosecution for allegedly accepting bribes. Or for Netanyahu's former deputy security adviser, who has also been jailed on suspicions of having been paid off. And, of course, for Ganor himself, who initiated the deal and is entitled to an initial commission of 0.8 percent of the total as well as a further 1.7 percent once it is finalized—an amount that would have amounted to around 50 million euros on the close to 2-billion-euro contract? Ganor is thought to have used a part of his commission to pay bribes to ensure the deal went through. The German share is 570 million euros, as promised by Merkel.

On December 22, 2015, two months before Netanyahu's visit to Berlin, Ganor invited Clemens von Goetze, the German ambassador to Israel, to lunch. They met in a restaurant in Tel Aviv and among those present were Netanyahu's cousin and legal adviser David Shimron. It remains unclear why the German ambassador met with the ThyssenKrupp representative, and what they talked about that day. The German Foreign Ministry confirms that the meeting took place but beyond a reference to "general foreign and domestic policy issues," refuses to say what was discussed. Did the meeting focus on details of the submarine deal?

Defense Minister Yaalon, for his part, attempted to block the purchase of the three Dolphins but was unsuccessful. Netanyahu's trip to Berlin led to a heated clash between him and the prime minister, during which Netanyahu argued Merkel might not have the political latitude to approve such a deal following the 2017 general election in Germany, and it was thus necessary to close the deal now. Besides, Netanyahu argued, it was his decision to make and not that of the defense minister.

A few months later, in May 2016, Netanyahu fired Yaalon. After that, the signing of the new, multibillion-euro deal no longer seemed like a question of when, but rather one of if. At least until Ganor fell into the sights of the Israeli attorney general.

At the end of last year, the Israel Police's anti-corruption unit Lahav 433 was assigned to the investigation and began wiretapping Ganor and monitoring his emails. In raids on his home, they seized tens of thousands of documents relating to the corvette deal. Real estate agents, who know Ganor from his previous career, recount desperate attempts to purchase apartment buildings in Berlin with large sums of cash after the first details of the investigation began to leak out.

The arrest warrant states that Ganor only obtained his position as a representative of ThyssenKrupp through the "unlawful intervention of a senior civil servant." He is said to have "been in a bribe relationship for years with senior civil servants." In addition, Ganor "conspired with another person by hiring his services in order to promote his business unlawfully," a reference to Netanyahu's cousin Shimron, who Ganor is believed to have promised a commission upon the closure of the deal for the three submarines.

When contacted for a statement, Shimron claimed he only acted as Ganor's legal adviser, and that there was no talk of a commission for the submarines. He said he never spoke with Netanyahu about the purchase of the vessels and his intervention with the Defense Ministry legal adviser had not been a conflict of interest. He insisted he followed the law at all times.

People close to Netanyahu say the prime minister denies all accusations leveled by former Minister Yaalon, stressing Netanyahu is not a suspect in the investigation. The prime minister, they say, is convinced "the accusations against Shimron will also prove to be untenable."

Gradually, the investigators expanded the investigation and convinced Ganor to cooperate. "Ganor has not merely been speaking, he has been singing," says one Israeli official involved in the investigation. According to a ThyssenKrupp spokesman, the company "immediately suspended its business relationship with sales representative Ganor and launched an internal investigation." In the summer, the company handed over a 100-page report to Israeli prosecutors along with several documents.

So far, the German chancellor has attempted to divide her position on Israel into two worlds—one realistic and the other metaphysical. In the first world, there are day-to-day political problems, such as the disappointments she has had in her dealings with the hardliner Netanyahu. The metaphysical world is characterized by unlimited solidarity with Israel that can be questioned by nothing and nobody. The hope is that the metaphysical world will not be implicated by the real world. But in the face of this affair, is this division still tenable?

This spring, after the news first broke about the suspicions of corruption, the Chancellery initially hoped it could extract itself from the scandal with a contractual change. Merkel's people requested that a clause be inserted into the contract stating the German government held the right to withdraw from its commitment to finance the submarines if the suspicions of bribery were corroborated. The calculation was clear: Court proceedings are protracted and the parties are considered innocent until proven guilty. Who knows what might happen in the next two or three years?

But that was before Ganor began talking. His confessions and the ongoing investigation that will very likely result in charges and convictions have trapped the chancellor in a dilemma that will be hard to solve. It will be very difficult for Merkel to explain to the public why she wants to proceed with a defense project that materialized in part through criminal insider relationships and very likely resulted in the loss of German taxpayer money. At the same time, putting a stop to the defense deal could also shake the foundations of Germany's unlimited solidarity with Israel and punish an entire country for the actions of a criminal gang.

Is Germany supplying Israel with technology for nuclear arsenal?

A new request from Jerusalem has complicated the situation further. The Israelis recently requested that ThyssenKrupp make structural modifications to the sixth submarine: They would like the vessel to be more than one meter longer than originally planned. But what is the purpose of the modification?

Experts believe there are two possible explanations. One is that the extension would enable the submarine to carry additional personnel. The other, however, is that the conventional submarine could then be retrofitted with a vertical launch shaft for nuclear-armed cruise missiles that the Israelis would then add to the vessel after delivery. Thus far, if the Israelis theoretically wanted to launch a nuclear-armed missile, they would have to use a hydraulic system involving a special torpedo tube in the bows. The launching of missiles through an upward shaft would be considerably easier. Is Germany, then, supplying Israel with vital technology for its nuclear arsenal?

Cabinet members from the center-left Social Democratic Party in the German government coalition insisted on an additional review of the export of the extended submarine. Once completed, the Federal Security Council, which approved the deal years ago, was to deliberate on the findings. The Chancellery commissioned Germany's foreign intelligence service, the Bundesnachrichtendienst (BND), with compiling a technical report, but the agency ultimately issued softball findings. The intelligence agency concluded the extended vessel couldn't do much more than the old one could.

That sufficed to assuage the Social Democrats. On June 28, the Federal Security Council voted unanimously to approve the export of the sixth submarine.

But the federal election in September has changed the political climate in Germany. The right-wing populist Alternative for Germany (AfD) now has seats in parliament and party faction leader Alexander Gauland already questioned Merkel's position on Israeli-German relations on the weekend of the election. Furthermore, it remains unclear how the business-friendly Free Democratic Party (FDP), one of the likely coalition partners in Merkel's next government, will view arms exports.

That is why Merkel had pushed internally for the deal for the three new submarines to be signed before the Bundestag election. With the expansion of the investigation in Israel, however, concerns began building in Berlin as well. Ultimately, the Chancellery postponed the signing, which had been planned for July, and no new date has thus far been set.

When contacted by DIE ZEIT for a statement, the Chancellery said Germany's participation in the financing of the corvettes shows the country "remains committed to its special historical responsibility for the security of the Israeli state, which is unconditional." Merkel's team was unwilling to comment on the submarine deal.

Israel has kept close tabs on the political shifts in Berlin. At the beginning of September, President Reuven Rivlin visited the chancellor. His initial plan had been to attend the inauguration of the memorial to the victims of the terrorist attack against Israeli athletes at the 1972 summer Olympic Games in Munich. But out of concern that the German submarine deal might fall through, he also added a quick visit to Berlin.

Merkel received Rivlin on the eighth floor of the Chancellery. The official part of their talks focused on Iran and its ambitions in the region. But when Merkel and Rivlin stepped out onto the balcony and spoke in private for a few minutes, the Israeli is said to have presented his government's request to be able to purchase the submarines as soon as possible. The view among virtually all parties in Israel at the moment is that the vessels are indispensable for the Jewish state's security, Rivlin argued. Merkel is said to have promised to address the issue immediately after the election.

When contacted, a spokeswoman for Rivlin said the president thanked the German chancellor for her recognition over the years of Israel's security needs—also "in relation to the submarines, which provide a decisive contribution to the security of the Israeli state."

As the chancellor continues to wrestle with the issue, Ganor has signed a deal with the judiciary. He has turned state's witness and the agreement foresees him spending a year in jail and paying a fine of the equivalent of 2.5 million euros.

Indeed, it's possible that the man who so massively damaged German-Israeli relations could get out of jail even before the chancellor is able to make her decision about the future of those ties.

Reprinted with permission from DIE ZEIT .

Translated by Charles Hawley and Daryl Lindsey.

Ronen Bergman, a senior correspondent for military and intelligence affairs at Yedioth Ahronoth and a contributing writer for The New York Times Magazine and, is the author of the forthcoming “Rise and Kill First: The Secret History of Israel’s Targeted Assassinations.”