How an extremist Hamas leader became Egypt's strategic asset

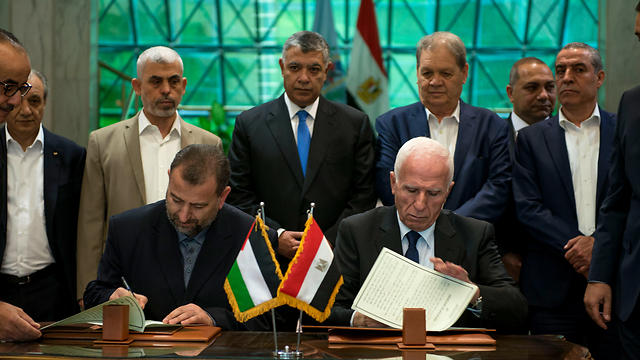

After being hunted by the Shin Bet for years, Yahya Sinwar has a new cause for concern. As the person leading the reconciliation process with Fatah, he has gained many enemies—from Iranian intelligence in Beirut to Mohammad Dahlan’s supporters in Gaza. It's no wonder he’s one of the most heavily guarded people by the Egyptians, who see him as their most important investment in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Sinwar, a former head of Hamas’ military wing, is Egypt's most important strategic investment today in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. He is the key to fulfilling Egyptian dream to restore its position as the most influential Arab state in the region, the one everyone would approach to put an end to the rift within the Palestinian society, which would force Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to sit down with a united Palestinian leadership for talks on a permanent agreement.

By the way, the Egyptian appetite to restore its status as the leading Arab country isn’t limited to the Israeli-Palestinian issue. The Egyptians see themselves as the main axis that will lead to a reconciliation in Syria. In talks with world leaders, including Israeli leaders, they present themselves as the only ones capable of talking both to Netanyahu and to Syrian President Bashar Assad, both to Russian President Vladimir Putin and to US President Donald Trump, as well as to the Kurds and the Druze, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan and even the Iranians. They believe they are the only ones who can square the Syrian circles. They are just waiting for Israel to turn to them for help on a permanent agreement in the Golan Heights.

The massive security around Sinwar didn’t begin when he landed in Cairo last week to take part in the practical stage of the reconciliation talks between Hamas and Fatah. The Egyptian General Intelligence Directorate has been “closing in” on him for several weeks now, even in the strip, as a result of a lesson they learned after losing a precious strategic investment in Gaza due to insufficient alertness.

In 2012, the Egyptian General Intelligence Directorate invested in Sinwar’s “Siamese twin,” Ahmed Jabari, who was known in Israel as “Hamas’ chief of staff.” The Egyptians “reeducated” Jabari in a bid to turn him into the spearhead of Egyptians interests in the region: From disconnecting Hamas from the jihadist movements in Sinai to gaining control of the intensity of the friction between Israel and Hamas and the dialogue between Hamas and Fatah.

Egyptian intelligence officials began sensing that their investment in Jabari was bearing fruit. But the Israeli Shin Bet—led at the time by Yoram Cohen and Nadav Argaman, his deputy and the organization’s current head—were unimpressed by the Egyptian effort and by the possibility that Jabari would have a positive influence on Israel’s security situation.

On November 14, 2012, as the two sat in the Shin Bet operations room, Argaman gave the order to launch a missile from “an Israeli aircraft” at a vehicle carrying the man who the Shin Bet saw as its No. 1 assassination target. Jabari was killed on the spot. It was the opening shot of Operation Pillar of Defense. The Egyptians lost an important asset and investment as far as they were concerned, and to this day they keep telling every Israeli who is willing to listen: “You were so stupid…”

There is still a fear today—both in Egypt and in Hamas—that Israel, which is seen as a country that will do everything in its power to avoid the negotiating table, will assassinate the current asset too. And if Sinwar is the key leading to the negotiating table, Hamas and the Egyptians believe there is a chance Israel will target him.

Meanwhile, Sinwar’s immediate enemies are internal. The man broke Hamas’ DNA, so the circles of people seeking his death are expected to grow as the talks with Fatah progress.

Hard to tame

The director of the Egyptian General Intelligence Directorate, Khaled Fawzy, knew the panther he was adopting would be hard to tame. Sinwar spent most of his life behind bars, either in the Israeli prison or in in the Gaza Strip, which is a different kind of prison. He has no real knowledge of the political-diplomatic world. He knows what’s good for the refugee camps and for the movements. His provinciality, the fact that he sees the world in black and white, and his inflexibility, fanaticism and loads of charisma, create a personality which is built for dramatic changes.

With the help of the Palestinian Authority and Israel, the Egyptians “orchestrated” the most serious humanitarian crisis Gaza had seen since Hamas’ rise to power 10 years ago, and then created a solution which required him to make tough decisions—and he made them on his own. So far, Hamas hasn’t let one person make major strategic decisions leading to a change of policy. It always had to be approved by the Shura Council, the political bureau, or both. It always took time, and there was always a consensus about the decisions.

Sinwar made several extremely dramatic decisions on his own: Abandoning Qatar, Erdogan and the Muslim Brotherhood movement in Egypt, and seeking political and economic Egyptian support; giving up the civil rule in the Gaza Strip in favor of an ideological rival which was defeated in a glorious revolution in 2007, and admitting Hamas government’s failure in running day-to-day life in the strip; and gradually severing ties with Islamic State members in Sinai.

Sinwar was able to do so because about 40 percent of the Hamas leadership in the strip is affiliated with the organization’s military wing. Moreover, more than one-third of the members of Hamas’ executive committee are released prisoners like him. And most importantly, Sinwar enjoys wide popular support, being the first Hamas leader to present the public in Gaza with some kind of a solution in the form of a reconciliation with Fatah, which may improve the public’s life and remove the Egyptian isolation. Unlike Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas, Sinwar has a mandate. According to internal polls conducted by the PA itself, the public support for Abbas is very low. President Trump has higher approval ratings among the American public on a bad day than Abbas’ approval ratings among the Palestinian public on a good day.

But the decisions made by Sinwar, without the acceptable consensus in decisions made by Hamas so far, have created rifts among different interested parties inside and outside Gaza, whose position is threatened by the connection with Egypt and the internal Palestinian reconciliation.

Mohammad Dahlan’s loyalists in the Fatah leadership in Gaza, for example, are very unhappy with the idea that Dahlan—who was pushed to the strip by Egypt as a leading element in the reconciliation process between the organizations and as a potential Abbas successor—was pushed aside upon the PA’s return to the strip in a leading role. Abbas wouldn’t like to see Dahlan or any of his people in a senior position in the strip. Any progress in handing control of Gaza over to Abbas would take Dahlan out of the picture, and his men would find themselves voiceless again. The Egyptian intelligence chief is thus seen as one of the best poker players in the region: Fawzy used Dahlan to push Abbas into the process. As soon as Abbas was caught in the trap and agreed to the talks, Dahlan’s role was over.

At the moment, the biggest obstacle in the reconciliation agreement between Hamas and Fatah is the security issue: Who will be responsible for security in the Gaza Strip and what will happen to Hamas’ security apparatus and to the organization’s military arm. In an attempt to delay the inevitable, the Egyptians are trying to convince the two sides to wait with the issue until an agreement is signed with Israel. In order to keep holding onto an independent military force, and in order to satisfy the PA—which is demanding one weapon, one law and one government—the military Hamas will keep a low profile in its training and weapons tests. Decisions to attack Israel will be made after consulting the PA.

These security issues should be solved, eventually, in a joint committee with Egypt and other Arab states. This was decided in 2011 in the Cairo Agreement, which includes all the components of the political integration between Hamas and Fatah, like election systems and military and civil cooperation. The Cairo Agreement serves as the basis for the discussions being held these days between Hamas and the PA.

Sinwar already fractured Hamas’ monopoly over security in the strip in his agreement to discuss handing some of the policing roles in Gaza over to the PA. In the preliminary talks, the Egyptians presented solutions which were not rejected out of hand, like handing parts of Gaza’s interior ministry to the PA, including handing the responsibility over the Gaza police to the interior minister subject to Palestinian Prime Minister Rami Hamdallah, which means Hamas will be conceding some 12,000 armed policemen. One of the disputes is over what will be done with those policemen’s weapons—will they be transferred to the PA as well or remain in Hamas’ hands?

On the other hand, Hamas has announced it has no intention of giving up the secret internal security apparatus, which the regime relies on. This apparatus includes some 6,000 Hamas members who are involved in activities against subversive groups. Only recently, its members arrested the apparatus’ No. 1 wanted person, ISIS leader in the strip Nur Issa, along with a group of his associates. What will happen to the apparatus in the new agreement remains unclear, but Hamas has already give up its presence in the Rafah Crossing, which will likely be handed over to the Presidential Guard—a PA apparatus in Ramallah which will also guard the new government.

Three birds with one stone

The senior Hamas members surrounding Sinwar believe these small security concessions are just the beginning. Hamas’ military wing includes a very strong ideological group, part of which supports the jihadist battle against Israel and the region’s “rotten regimes” and whose members are concerned about what they see as a clearance sale of the Hamas movement.

The military wing also includes a group of pro-Iranian leaders. The thawing relations with Egypt are pushing Iran and Hezbollah out of Gaza, after years of financial and professional support to Hamas’ military wing. The members of the pro-Iranian movement are afraid that a years-long investment will go down the drain—along with their high positions.

The man most affiliated with the renewed relations between Hamas and Iran, politburo chief Ismail Haniyeh’s new deputy Saleh al-Arouri, may have been chosen to head the Hamas delegation to the talks with the PA in Cairo, but that hasn’t helped ease the concerns of senior pro-Iranian Hamas leaders—like military wing commander Marwan Isaa or Mahmoud al-Zahar. Like other senior Hamas members, they may reach the conclusion that Sinwar is a sort of adventurer who is taking unnecessary risks and endangering the Hamas movement.

The Iranians, on their part, haven’t halted their subversive activity against Israel in Gaza and in the West Bank for a minute. Any reconciliation attempt that may thwart this activity only increases their appetite to remove any disruptive elements from the arena. Iranian intelligence agency officers in Beirut are operating Palestinian cells and agents in the West Bank and Gaza, and are capable of assassinating Sinwar without batting an eyelid.

Al-Arouri’s appointment as head of the delegation is an attempt by Sinwar and Haniyeh to kill three birds with one stone: To hush Iran’s supporters; to neutralize the supporters of the former politburo chief, Khaled Mashal, who doesn’t approve of these moves; and to ensure that the West Bank is represented too, as al-Arouri was recently elected the movement’s leader in the West Bank.

The list of opponents is also joined by senior Hamas government workers, who will be forced to vacate their seats in favor of the ministers’ bureaus from Ramallah and suffer mass dismissals. There are also Salafi organizations that are persecuted by Hamas and are openly threatening Sinwar and his people. This threat includes the possibility of stepping up the rocket attacks on Israel to get the Hamas leadership in trouble with Israel and torpedo the political moves.

We saw an example of that last week. The IDF responded to a rocket attack from the strip with insignificant artillery fire, as Israel doesn’t want to disrupt a move led by an important friend like Egypt with the support of the United States, Russia, the United Nations, the European Union and most of the Sunni world.

At the moment, Israel is avoiding taking any steps that would thwart the reconciliation attempts between Hamas and Fatah, as it assumes they won’t reach a decisive point that would require its intervention. Israeli officials believe there is a good chance the reconciliation move will fail just like six similar moves that have been launched since 2007, so it is letting the Egyptians entertain themselves. The entertainment will end when it turns out that Israel’s strategy of separating between Gaza and the West Bank, in the 12 years that have passed since the disengagement to avoid a real diplomatic process, is no longer relevant.

Yahya Sinwar is aware of the many enemies he is gaining. In recent weeks he has been addressing different forums, mainly young people, in a bid to convince them that he has chosen the only reasonable move that will keep Hamas alive. He has a message for his enemies too. In those meetings, he says he will break the neck of anyone who opposes the reconciliation move. And when Yahya Sinwar promises to break someone’s neck with his bare hands, he should be taken seriously. He has already done just that to one of his opponents, and not so long ago.

Sinwar’s ability to make decisions and lead to changes in Hamas’ strategy is not just his advantage but also his biggest disadvantage. If the move fails, the same Sinwar will have to make a radical change ahead of an all-out conflict with the Egyptians and with Israel.