It’s time to change Israel’s provincial defense policy

Op-ed: Our political-security echelon isn’t solving or dealing with problems; it's simply postponing them, passing them on to the next generation. It’s as if everything beyond Hezbollah, Hamas and Iran doesn’t exist. It’s as if the world around us hasn’t changed.

It’s as if the headlines were taken from the previous century: The Syrians fire rockets at open areas, Israel destroys Syrian cannons in response, the Iranians threaten to deploy Shiite forces in Syria, Israel announces “red lines” and threatens a military conflict, Fatah and Hamas hold futile talks on a unity government, the prime minister declares Israel is suspending talks with the Palestinians, and everyone here applauds the security and political echelons. There, we showed them the meaning of deterrence.

But what we are seeing here is a provincial defense policy, a false representation of a leadership that barely sees beyond the tip of its nose and is busy putting out fires day and night.

It’s a leadership that sees national security through a narrow regional viewpoint. It’s as if everything beyond Hezbollah, Hamas and Iran doesn’t exist. It’s as if the world around us hasn’t changed in the past decades, and we are stuck in the era of aggressive solutions in the form of reward and punishment as the main political-security activity.

The current political-security echelon isn’t solving problems, isn’t dealing with problems, but simply postponing them, passing them on to the next generation with the use of force.

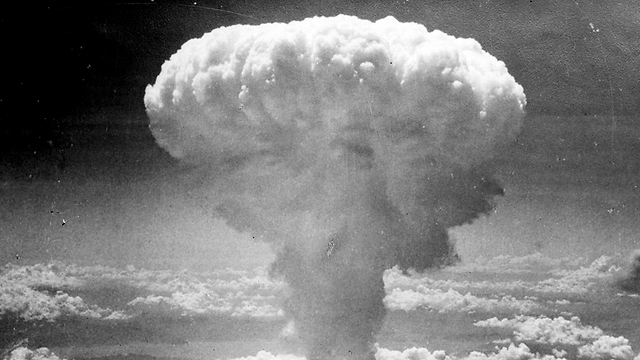

The Israeli security worldview, if there is one, was consolidated somewhere in the Cold War era. There were two world powers at the time—the United States and the Soviet Union—which had complete dominance over the production and use of nuclear weapons. Over the years, the two powers formulated rules for the game that created mutual deterrence. At the time, the chance of a local clash in any corner of the globe sparking a nuclear conflict was low.

In the Six-Day War and in the Yom Kippur War, the Russians threatened to use a nuclear weapon to curb Israeli achievements. But they were likely unwilling to enter a nuclear conflict with the Americans over that.

But times have changed. Today, the world has nine nuclear countries. They are active in different arenas, in places with different rules of the game, and they are threatening to use their nuclear weapons in local conflicts as well.

Take India-Pakistan, for example. There are no clear rules of the game today, no control over the number of missiles capable of carrying a nuclear warhead. The Pakistanis aren’t bothering to produce missiles they can neutralize after the launch, in case of a mistake, and no one understands North Korea’s logic. It’s no wonder Japan and South Korea are on the verge of becoming nuclear states, and the Iranians are following in their footsteps.

The world is a much more dangerous place in terms of the nuclear threat compared to the 1960s and 1980s, and it will become even more dangerous over the next decade, when other countries join the nuclear club. Such an explosive world requires a great amount of caution, in every corner across the globe. When you strike in Syria, you must take into account it could cause a regional and even global chain reaction. A crisis between India and Pakistan, or a nuclear crisis between the US and North Korea, can have ramifications on Israel as well.

In such a situation of an unclear nuclear game, countries rely less on the use of military force for solving problems, and more on the use of “soft force”—all the systems that won't lead to an explosive chain of events to achieve political goals: Diplomacy, media and economic leverages, psychological warfare, cyber warfare, the secret activity of special forces and intelligence agencies, use of low-signature systems to target the enemy and maintaining strategic ambiguity so as not to force the enemy to respond. In other words, Less tanks and more thought.

But Israel isn’t there yet. It isn’t by chance that Israel was excluded from the nuclear agreement with Iran, and that it’s being excluded from the agreement in Syria—it’s because Israel is not properly using the “soft” measures at its disposal—if at all—to reach diplomatic-regional achievements. And when you fail to implement soft abilities, the only option left at your disposal is to bomb three Syrian cannons out of an old habit and creating an illusion among the public that you solved a problem.

Israel does have “soft” abilities. Pushing Hamas into the Egyptians’ arms and pushing the Muslim Brotherhood away from Gaza is an example of a strategic achievement that was the result of proper economic and diplomatic moves. We don’t always have to bang our head against a brick wall.