The Shin Bet’s secret activity in Israel’s Arab schools

Confidential documents obtained by Yedioth Ahronoth reveal how Israel’s internal security service operated in the Arab sector for years, in cooperation with the Education Ministry, to remove teachers and principals and thwart the appointments of educators considered hostile to the State of Israel; in many cases, the disqualified teachers were unaware of the real reason for their dismissal.

When the door to the office closes shut, the Education Ministry's director-general and Prime Minister Menachem Begin’s advisor on Arab affairs remain in the room too.

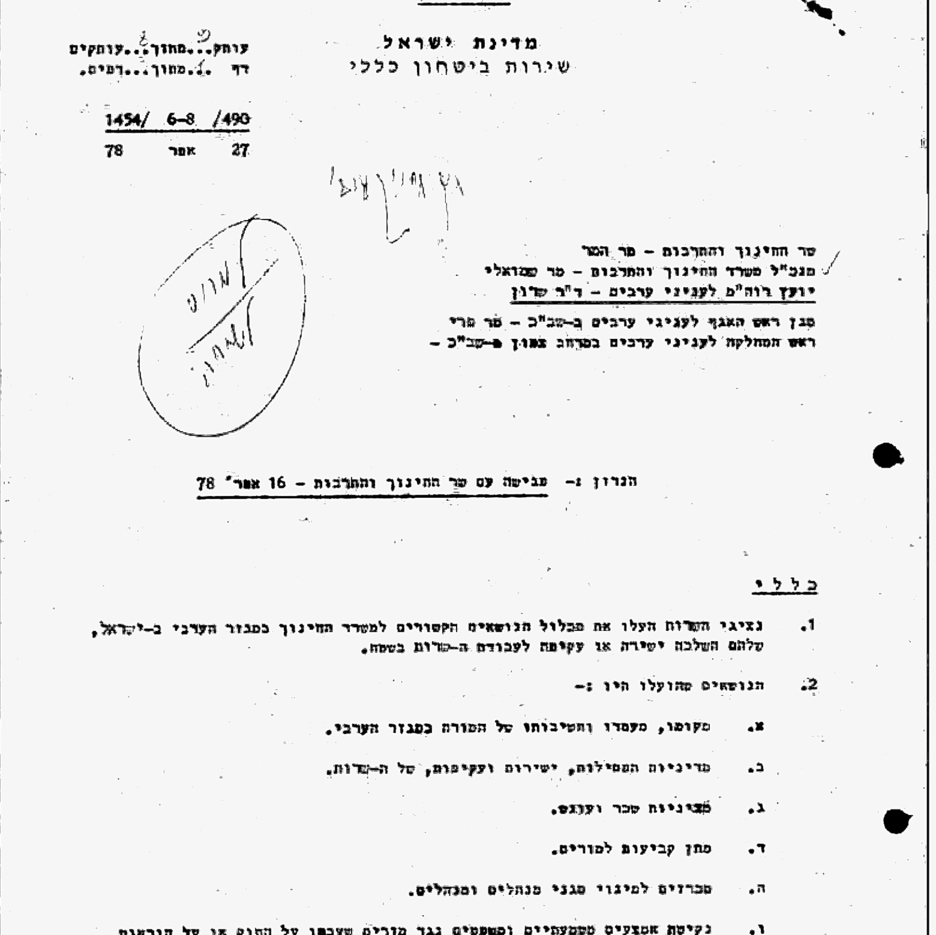

An indication of the confidentiality of the meeting—whose very existence was kept secret until now—can be gleaned from the "Top Secret" heading atop the three-page document disseminated several days later by B., head of the Shin Bet's Arab affairs division.

This extraordinary document summarizes the contents of that eyes-only meeting. It documents in writing, on official Shin Bet letterhead, agreed-upon fundamentals for the manner in which security oversight will be placed on teachers and principals in the Arab sector, and how Shin Bet operatives will be able to work behind the scenes to remove educators, implement a policy of "reward and punishment" and even be clandestinely involved in tenders for school principal appointments.

For decades, in the early days of the State of Israel, it all sounded like an urban legend; bits and pieces of information making the rounds about Shin Bet involvement in the Arab sector's education system: anonymous G-men pulling strings to remove Arab teachers and principals considered hostile to the state.

Only in the early 2000s did state officials admit that a senior Education Ministry employee was, in fact, a Shin Bet operative—and a petition was filed with the High Court of Justice to remove him from there.

This particular incident notwithstanding, not much was known of the manner in which the Shin Bet worked covertly within the Arab sector's education system, and of its involvement in the decision-making process and staffing issues in the sector over many years.

New testimonies and documents uncovered by Yedioth Ahronoth, including top-secret Shin Bet records, shed light on the Israeli intelligence's wheeling and dealing through the years in Israeli Arab educational institutions and on the manner in which appointments of educators who were suspected to be a security risk to the State of Israel—dubbed "disqualified"—were blocked or terminated, with not only consent but also collaboration from Education Ministry officials.

In fact, the Shin Bet went so far as to appoint or disqualify school principals.

The written records show the marked educators usually never had a clue why they one day suddenly found themselves out of a job, or knew of the unseen hand that had marked them as "disqualified."

Other obtained testimonies point to attempts to work against Arab educators who weren't even directly suspected of hostility towards the state, but had a family member who was hostile—making them guilty of "indirect disqualification," as the Shin Bet termed it.

"I'm happy this is no longer the case," says Carmi Gillon, a former Shin Bet director.

‘Abusing their academic chair’

As a country embroiled in bitter existential battles since its inception, Israel has been understandably vigilant when it came to education, working diligently to prevent abuse of the influence teachers have over the younger generation to harm the country.

Indeed, there is little doubt the Shin Bet has been doing an important job for years, working to prevent incitement and the infiltration of hostile entities into the field of education. Having said that, in light of the testimonies to follow below, one may be moved to wonder if these noble ends truly justified all of the means delineated in this article.

From a very early stage, the Arab sector bristled with different testimonies pointing to the Shin Bet's involvement in the education system.

"The story of the Shin Bet’s involvement in education system appointments was an open secret in the Arab society, dating back as far as 1948," says attorney Hassan Jabareen, general director of Adalah—The Legal Center for Arab Minority Rights in Israel.

"During the period of military administration, for instance, there were reports about Shin Bet operatives sending messages, such as ‘If your son continues to be involved with Maki (the original Israeli Communist Party—ed), he will no longer be a teacher.’

"It wasn't common knowledge among the general Israeli public, but we certainly knew. We knew someone was out there supervising education at all times," Jabareen adds.

Sure enough, over the years the Shin Bet closely monitored what was going on at Arab schools in Israel as well as educators, and—when deemed necessary—acted against them.

An example of such activity can be found in internal Education Ministry documents we obtained, dealing with an Umm al-Fahm high school.

In March 1976, the ministry's legal adviser corresponded with its director-general, Eliezer Shmueli, warning him of "incitement" in the school. According to the adviser, the Umm al-Fahm local council should be cautioned that if the matter is not dealt with, the ministry would "consider a closure order."

Information about the supposed incitement plot, the missive said, was gleaned from a document provided by the Shin Bet.

A different letter on the same topic, sent a year later to Director-General Shmueli, said the situation in the school "remained the same, save for the fact the warning didn't do any good." This information too, it was noted, came directly from the security service.

The Shin Bet was not the only provider of information on Arab sector educators. A correspondence between Prime Minister's Office employees, for example, reported a quote made by a Sakhnin high school teacher during a lesson.

"Who does (then-Egyptian President Anwar) Sadat want to make peace with? Begin the fascist, the terrorist who carried out the Deir Yassin massacre? Is that the kind of person Sadat wants to make peace with?" the teacher was quoted as saying.

"Is it not the time to get some order with teachers like this?" wondered a letter addressed to several Shin Bet officials, and even to Prime Minister Begin as well.

Dr. Moshe Sharon, the prime minister's adviser on Arab affairs, responded in a letter addressed to the Shin Bet, saying: "What this teacher said is a symptom of an undercurrent within the education system wherein Arab teachers abuse their academic chair to disseminate their political opinions and to preach a bully pulpit of nationalism… My suggestion is to react harshly in this case, and in similar cases we have been monitoring."

The Shin Bet didn’t settle for intelligence updates from the ground. Testimonies show it went to great lengths throughout the years to influence the Arab sector’s education system. In April 1978, in Minister Hammer’s office, the organization tried to institutionalize its ability to operate behind the scenes.

A review of the secret Shin Bet document summarizing that meeting points to the Service’s intimate involvement in the Arab sector’s education system.

“The Service’s representatives raised all the issued concerting the Education Ministry in Israel’s Arab sector which have a direct or indirect impact on the Service’s activity on the ground,” the document stated.

The issues discussed in the meeting included the teacher’s status and important in the Arab sector, direct and indirect disqualification policies, reward and punishment policies, teacher tenure, tenders for the appointment of principals, etc.

After the general introduction, the document got down to business. First, it dealt with directly disqualifying Arab educators from teaching at schools—as a result of the educator’s actions.

The Education Ministry appeared to have no problem with that. “As for direct disqualifications, the Education Ministry will adopt our recommendation,” the Shin Bet document stated. “The Education Ministry’s director-general asked us to hand the material over to his office along with the reason for the disqualification.”

In the case of indirect disqualifications—in other words, denying a teacher a job due to his relatives’ actions, with no involvement whatsoever on the candidate’s part—the Education Ministry wasn’t keen on cooperating with the Shin Bet.

“The education minister’s position is that if there is no negative security information on a candidate for a teaching positions, and if the candidate isn’t subject to negative influence from his close relatives, it would be very difficult to indirectly disqualify the candidate,” the document said.

The next part of the document summarizing the meeting is titled Reward and Punishment Policy. It states that “the Education and Culture Ministry will try to accommodate the Service’s request in adopting our recommendations on encouraging positive teachers.”

The third segment, Teacher Tenure, points to the extent of the Shin Bet’s involvement in Arab schools, revealing that a teacher would only be granted tenure after hearing the Shin Bet’s opinion.

It turns out the Shin Bet was also involved in tender committees for the appointment of educators. “The education and culture minister has agreed,” the document stated, “to let us pass any negative security information on candidates for principal and deputy jobs to the Education Ministry’s representative in the tender committees.”

The penultimate segment of the document is perhaps the most interesting, stating that the Education Ministry would employ a sort of “agent provocateur” on behalf of the Shin Bet: “The education minister suggested the appointment of a representative of the Service as a full-fledged employee in the Education and Culture Ministry’s Arab Education Department, to coordinate the Service’s activities in the ministry. The employee will also deal with other issues related to the department.”

Pulling some strings

These far-reaching agreements didn’t remain on paper. Testimonies and documents obtained by Yedioth Ahronoth describe the Shin Bet’s discreet activity in the Arab sector and reveal how “disqualified” educators were suddenly kicked out of the system without being informed of the real reason for their dismissal.

M. was a science teacher at the local council of Tur’an in the Lower Galilee. He was disqualified following information received by the Shin Bet, and his employer—the Tur’an Local Council—was informed by the Education Ministry that it was vetoing his employment as a teacher.

Documents from that time, November 1978, reveal the Education Ministry was asked to reconsider its decision due to a shortage of science teachers in higher grades. At the same time, negotiations were held behind the scenes with the Shin Bet.

Eventually, the documents reveal, the Shin Bet provided the ministry with an approval to keep employing the teacher temporarily, “for the sake of the students, who are about to take their matriculation exams.” It was clarified, however, that the teacher “must not be employed as an educator in the next school year under any circumstances.”

And indeed, the following year, the Education Ministry refused to let the Tur’an council keep M. as a teacher. The reason for his disqualification and the Shin Bet’s involvement behind the scenes were concealed. “We are not permitted to indicate that the teacher’s job has been terminated for security reasons,” a senior Education Ministry official noted in a discreet document about the Tur’an teacher.

The incident, however, reached a Channel 1 television program called “Between the Citizen and the Authorities.” When the show’s producers tried to obtain information about the dismissed teacher, Education Ministry officials stressed out.

An internal ministry document signed by Emmanuel Kopelevich, who served at the time as head of the ministry’s Arab Education and Culture Department, describes the unusual chain of events. “I have no suggestion on how to respond to the show’s producer regarding this matter,” Kopelevich wrote to a ministry official. “I think we should find a way, through the television’s management or through the Israel Broadcasting Authority management, to prevent this matter from being raised on this show or on any show… by pulling some strings, if needed.”

Another educator, Ramzi Suleiman, started working as a counselling psychologist in a teachers’ seminary in northern Israel, until one day an order was received from the Education Ministry to dismiss him.

In an effort to change the decision, a senior official at the seminary turned to the Prime Minister’s Office. Officials at the Prime Minister’s Office began discussing the issue in October 1978, trying to understand why the teacher had been disqualified—and whether the Shin Bet had anything to do with it.

The mystery was solved when Kopelevich confirmed that the Shin Bet had indeed been behind the educator’s disqualification. “Those days, we were contacted by D. from the security service in Haifa… He asked if Mr. Ramzi was employed and informed us that they were against his employment,” the Education Ministry official wrote in response to an appeal from the Prime Minister’s Office.

Kopelevich added that he had contacted the seminary principal himself and informed him that “we are unable to approve the employment.” Later, he added, the ministry received a message that “the Service would possibly withdraw its objection, despite the evidence against him, due to the intervention of different elements.”

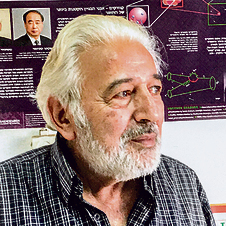

Ramzi Suleiman, the counselling psychologist, is today a veteran professor who served as chair of Haifa University’s Psychology Department and specializes in behavioral sciences and exact sciences. He remembers that incident very well.

“A friend of mine, who was one of the Hadash representatives at the Teachers’ Union, gave me some pamphlets printed by the movement and asked me to hand them out to the teachers. I put them on the table and didn’t even hand them out, but because of the Shin Bet’s dominance and the atmosphere of suspicion at the time, one of the teachers informed the principal about it. The principal was scared and informed the Shin Bet. Later, the principal explained that he had no choice but to report it, otherwise someone else would have report it. That’s when the order was issued to dismiss me immediately.

“A seminary representative asked if they could let me teach after all, as there was no substitute teacher. They asked me to meet with someone from the Shin Bet, but I refused, saying I hadn’t done anything wrong. Eventually, they had a meeting without me and succeeding in arranging for me to keep teaching.

“There was an atmosphere of fear and snitching at the time. Everyone was afraid someone would snitch on them, and if someone snitched on you, you didn’t get an appointment, you didn’t get a job. People suspected each other and were afraid to open their mouths in public. I kept hearing the saying ‘walls have ears.’

“I’m not the only one. Many people experienced similar things. A lot of slots in the education system, Arabs’ niches, were filled with pathetic rather than dignified figures. They chose their own people.”

No negotiations

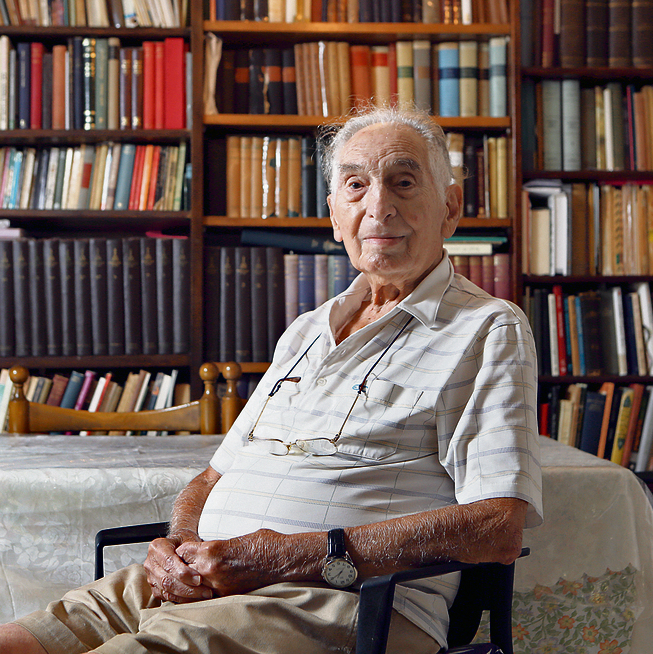

For 16 years, until 1987, Kopelevich was in charge of the Education Ministry’s Arab Education and Culture Department. We met with him at his Jerusalem home. “This whole business took place under extremely difficult conditions,” he recalls as he describes the Shin Bet’s disqualification system behind the scenes.

“After the formal meeting between the Education Ministry and the security service (at Minister Hammer’s office in 1978), the matters which had not been on the table became official. When a teacher from the Arab sector was disqualified for security reasons, the Education Ministry didn’t tell him he was dismissed or that he wasn’t accepted due to security issues.”

Did the General Security Service tell you, for example, not to employ a certain teacher?

“Yes, but not in writing.”

And then you didn’t hire that person?

“Right.”

Didn’t that person ask why he wasn’t hired?

“There were two channels, a formal one and an informal one. In the formal channel, the teacher was notified, and different people were told different things. In the informal channel, someone hinted to that person that he had been disqualified.”

Was there some kind of negotiation or did the Shin Bet have the final say?

“There was some kind of contact. There were cases in which a candidate was disqualified and I said, ‘Hold on, why?’ There was no negotiation. I never interfered in their considerations. They never explained why they disqualified a teacher.

“There are two interests here which sometimes contradict each other. On the one hand, the interest the security service is in charge of—to prevent people who act against the state’s best interest from setting foot in official institutions or educational institutions. None of us want that.

“On the other hand, there is the educational interest—wanting Arab children to get the best education possible, including the best teachers. In many cases in the Arab population, the finest people from an educational and leadership perspective have anti-Israel tendencies.

“This whole occupation with disqualifications was mostly reflected in the appointment of school principals,” Kopelevich adds. “There were few cases in which the Service rejected the finest candidates for principal and I was forced to take a second-rate educator, because the person who I saw as the most suitable candidate had been disqualified.”

‘Feeling of alienation’

The disqualified teachers were usually unaware of the reason for their dismissal or rejection, yet some insisted and asked questions. One of them was northern resident Awad Abdelfatah Hussein.

In the 1980s, he started working as an English teacher in the Galilee village of Arraba. One day he was fired, he says, in favor of a person who didn’t even have a degree in English studies. Fifteen years later, he tried to work as a teacher again, and even applied for an Education Ministry’s training program, which promised to provide suitable candidates with a job. Hussein completed the teachers’ training, but says he was the only one of the dozens of graduates who did not get a job.

In 1996, he petitioned the High Court of Justice, voicing his suspicion that the Shin Bet was preventing him from getting a job due to his political opinions and affiliation with the Bnei Hakfar (Sons of the Land) movement. “Over the years, I was questioned and arrested by the Shin Bet several times, but I was never charged in a court of law,” he told us recently.

We managed to obtain the minutes of a discussion held at the Education Ministry those days, which reveal why the English teacher was barred from pursuing his career. Ministry officials quoted comments made by the teacher, in which he had slammed the state, and mentioned meetings he had held with Jihad and Hamas representatives. “There is a concern that you may want to influence students and promote your ideas,” he was told by the Education Ministry’s director-general at the time, Dr. Shimshon Shoshani.

“That’s amazing. Do you show such an interest in every teacher?” the teacher’s lawyer fought back, noting later on that “my impression is this is a Shin Bet method.”

“It’s good to have someone who gathers information,” Shoshani replied. “The Shin Bet plays an important role here. My job is to ensure that no one suffers any injustice… We are not against radical teachers when it comes to education, but we are against radical teacher when it comes to being loyal to the State of Israel.”

Eventually, at the parties’ request, the petition was withdrawn. Although he had the option of resuming his teaching career, Hussein decided to give up. “It was a major blow,” he explains. “It isn’t easy being fired and going to work in construction. I felt a deep sense of alienation, as if I didn’t belong here.”

Dr. Shoshani offered the following comment: “We held a proper hearing, and the decision was based on what he said and voiced during the hearing. The quotes must be reviewed in the general context of what was said in the hearing.”

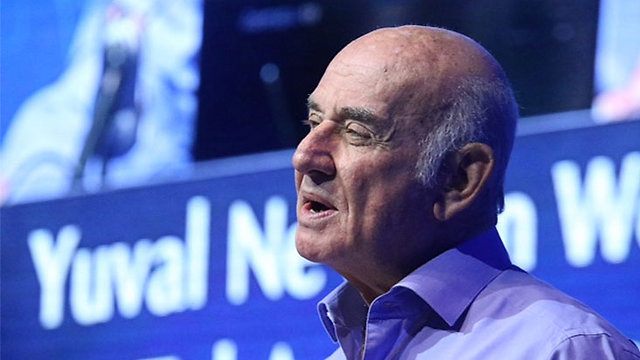

“People knew that the Service had a hand, and I’m being mild, in appointing teachers,” says Knesset Member Yaakov Peri, who served as Shin Bet director from 1988 to 1995.

“The decisions made in the state’s first decades were justified. Supervising populations would could pose a security risk is a legitimate thing that should be done in a decent and balanced manner, and as the years go by it is done in a more transparent way.

“As far as I remember, a person wasn’t disqualified for belonging to a certain movement. A person was disqualified if the opinions he voiced or his activity were seen by the Service as harmful.”

During his term, Peri was forced to deal with criticism which began surfacing against the Shin Bet’s activity in the Education Ministry. He even held a discussion with then-Education Ministry Shulamit Aloni.

“As culture minister, I didn’t approve of this interference. The military government days in Israel are long gone,” Aloni wrote in a document from 2001, in which she addressed her meeting with Peri. “The violation of civil rights wasn’t the only issue I raised. I also noted that we must consider the huge damage caused by the interference, such as a strife between clans, the selection of loyal (to whom?) yet unqualified teachers, and teachers whose status is undermined.”

Following the meeting, Aloni wrote, “I got the impression that the Shin Bet had found more important matters to deal with, which didn’t cause as much harm to the rights of Israel’s Arab citizens, and that the blatant interference in the appointment of principals and in influencing tenders (without an explanation and without early or late notice) had come to an end… I was so convinced that this matter had been solved, that I no longer dealt with the issue during my term. I may have been careless or perhaps naïve.”

Carmi Gillon, who replaced Peri as Shin Bet director, says the education minister during his term, Dr. Amnon Rubinstein, asked him to terminate the position of a Shin Bet official in the Education Ministry, and he approached Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin on the matter. “We began looking into the issue in a bid to prepare a concise position paper and put an end to it, and Rabin gave us his blessing,” he reveals. He believes the move was interrupted by the prime minister’s murder.

According to Gillon, the decision to have a Shin Bet agent inside the Education Ministry wasn’t necessarily a bad one. “I assume that until then, the Education Ministry would send the Shin Bet a letter stating, for example, that ‘Ahmad has applied for a teaching job in Tira,’ and the Shin Bet would say yes or no, and the other way around. It was a move aimed at creating a dialogue, rather than giving the Shin Bet veto power. This was a sensitive issue, and it wasn’t handled with sufficient sensitivity until 1978.”

Asked how many cases of disqualification he had to deal with, Gillon replies “very few.”

“I remember cases that came down to a decision between the best interest of the education system and the security demands, and then you have to decide whether to approve it or not. You have to get a bird’s eye view of the situation. What good would it do to disqualify all teachers in Umm al-Fahm and leave all children without a school?”

Another decade went by, however, before the Shin Bet position in the Education Ministry was officially cancelled. Only in 2004, following information complied by the Adalah center, a petition was filed against the Education Ministry, the Shin Bet and the Prime Minister’s Office. Adalah petitioned the High Court to put an end to the Shin Bet’s involvement in the appointment of educators in the Arab sector. The petition was supported by letters from three former education ministers who were in favor of removing the Shin Bet representative from the Education Ministry.

“I believed there was no longer room for security opinions on Arab candidates for teaching positions, but I was unable to cancel an existing routine… During my term, there was no security-related disqualification,” Amnon Rubinstein stated. “My opinion is that the Shin Bet’s involvement in the Education Ministry is wrong and should therefore be cancelled,” Yossi Sarid wrote.

The issue of the Shin Bet’s involvement in the Education Ministry was never discussed by the court, however. The state’s response to the petition was that as part of the Dovrat Commission’s reform, which focused on a comprehensive reorganization of the education system, it had already been decided to cancel the position of deputy manager of the Arab education department—the position held by the Shin Bet representative. The state’s announcement made the petition redundant and essentially prevented a further discussion of the issue.

“At that time, the Education Ministry admitted for the first time that this position existed,” says Prof. Ismail Abu-Saad, who was a member of the Dovrat Commission at the time. “Up until then, it was a top secret. It was raised for discussion in the Dovrat Commission, and the members said the position should be terminated urgently. We still live in a democratic country, and if someone committed a criminal or security offense, it should be dealt with by the police or the law. It must not be part of the education system’s work.”