Israel hands out deportation notices to African asylum seekers

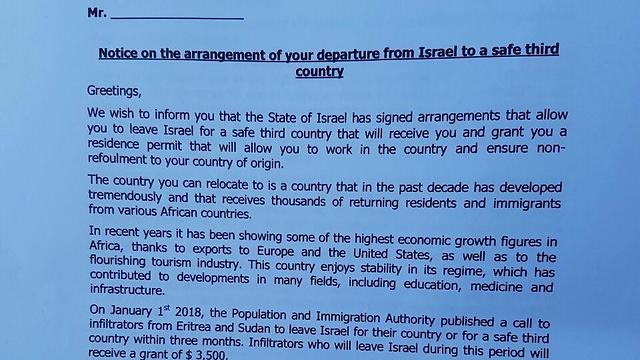

Letter describing the unnamed African destination country as having a 'flourishing tourism industry' and 'stability in its regime' details the penalties Eritrean and Sudanese refugees can face if they don't leave Israel: indefinite incarceration and financial sanctions.

Israel's Population and Immigration Authority started handing out deportation notices to asylum seekers from Eritrea and Sudan who arrived at its offices Sunday to renew their residence permit, as they are required to do every two months.

The candidates for deportation are single men who were not able to submit a request for asylum by January 1, 2018. The deportation letters summoned the asylum seekers to a hearing, during which they could make their case against being expelled.

If their arguments are not accepted and they do not leave "voluntarily" to an unnamed African country within two months in exchange for $3,500 and a plane ticket, they will be either be incarcerated indefinitely at the Saharonim Prison in the Negev or forcefully deported. Those forcefully deported will receive a "significantly reduced" monetary incentive than those leaving willingly, according to the deportation notice.

Meanwhile, 33 percent of a deposit made on their behalf will be subject to deducations as penalty for illegal stay in Israel. Israeli employers are required by law to deposit 20 percent of the African migrants' monthly salary into a bank account, which the migrants could then receive in cash or via bank transfer after passing border control at Ben-Gurion Airport.

Only a handful have received the letter so far, which claims the country they are due to be deported to—believed to be Rwanda—has "in the past decade developed tremendously, and that receives thousands of returning residents and immigrants from various African countries."

The letter further states that "In recent years, (this country) has been showing some of the highest economic growth figures in Africa, thanks to exports to Europe and the United States, as well as to the flourishing tourism industry. This country enjoys stability in its regime, which has contributed to developments in many fields, including education, medicine and infrastructure."

The deportation plan has sparked outrage in Israel, where groups of pilots, doctors, writers, rabbis, students and Holocaust survivors have appealed to have it halted. They say the deportations are unethical and would damage Israel's image as a refuge for Jewish migrants.

Debasai Berharabo, 50, who received a notice of deportation, came to Israel from Eritrea nine years ago. He currently resides in Netanya and works in a senior housing project.

"They told me I had to leave to a third country. They didn't say which one, but I know it's Rwanda. It's a danger country. People who have already gone there said it was not good there and that they left. My country isn't good either. I'm afraid to go back, or to leave to Rwanda," he said.

"If I don't leave in two months they'll jail me. Let them. I prefer prison, no matter how long I'm there. They don't understand I won't leave to my death. Prison is better than death," he stated.

"I've been here for years and everything was fine. I don't understand why we're being expelled. We've done nothing wrong. We all have jobs. I'm old now, why should I leave?" Berharabo demanded.

His claims were congruent with those of assistance organizations that accompany them during their stay in Israel, with both claiming expulsion poses a potential life risk for the expellees.

'Go to Rwanda? I'd rather be in jail'

Marawi Zauda, and 34-year-old Eritrean national, has been in Israel for 12 years and now resides in Pardes Katz. "They said if I don't go back (to Eritrea) in 60 days, I'll go to jail. They told me I could go back to Eritrea or move to Rwanda or Uganda. What's waiting for me in Rwanda? It's not my country. It's the same as Eritrea as far as I'm concerned," he said.

"I get nothing, only 3,500 dollars. I don't want money (anyway), I want to stay in Israel. Eritrea, Rwanda, Uganda—it's all the same to me, and I'd rather be in jail," Zauda said.

"I have a lawyer, I'll speak to her and we'll see what we can do," he added. "If I'm not going back to Eritrea, why should I go to Rwanda? I'm a human being. Nobody explained anything about what'll happen to me there."

"If I have to leave, I'll go back to Eritrea, to at least die in my own country. But I'm going to stay in Israel, in jail. I don't matter to me—a year, two years or ten years," he said defiantly.

According to Population Authority data, some 38,000 migrants are currently in Israel, 970 of which are incarcerated at the Holot detention center and 450 in the Saharonim prison.

The Knesset's plenum approved this past December an amendment to the Anti-infiltration Law, according to which the Holot facility will close down.

Right before the conclusion of 2017, Israel's Population and Immigration Authority published data that said no infiltrators entered Israel in 2017. Official requests for asylum were made, however, from 7,710 Ukrainian nationals, 1,682 Eritreans, 1,350 Georgians and 868 Sudanese.

Head of the Authority's Enforcement and Foreigners Administration Yossi Edelstein said that "Unfortunately (the Africans) abused Israel's asylum mechanism and submitted requests for asylum which we found to be groundless."

The Associated Press contributed to this report.