The Palestinian security prisoners’ internal court: Snitches get killed

In second part of special series of interviews, Palestinian terrorists released from Israeli prisons in 2013 talk about the brutal internal punishment system against prisoners accused of violence against fellow inmates or of tipping off wardens—from denying a prisoner’s right to buy at the canteen to killing collaborators.

In a series of interviews they gave Ynet after being released from prison, they said that over the years they often had high expectations for a release, but their hopes were shattered time and again for various reasons. At first, they thought the Oslo Agreements would bring their prison term to an end, but reality kept striking them in the face.

“Most prisoners felt they had been abandoned,” Esmat Mansour, who took part in the 1993 murder of Haim Mizrahi in Beit El, says about the weeks after the Oslo Agreements were signed. “And not just them, but all the issues we had fought for. We hoped we would be released earlier, but we were abandoned for 20 years. There has been mutual recognition between the Palestinian Authority and Israel for the past 20 years, but Israel hasn’t recognized the PA’s prisoners. As a prisoner, I felt there was something wrong here. What are you making peace for? What are you shaking hands for?”

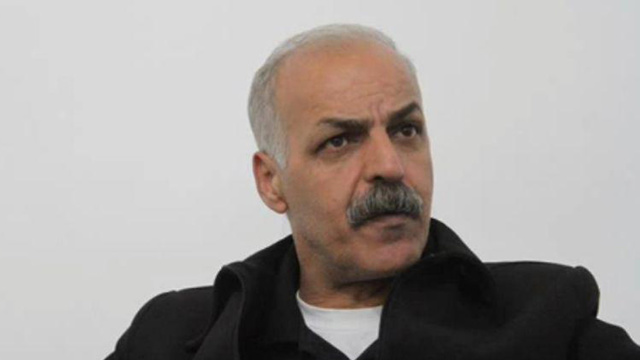

Haza’a Mohamed Sa’di, who murdered Yosef Eliyahu and Leah Elmakayes in 1985, believes the Palestinian leadership mishandled the prisoner issue. “I was disappointed by the fact that when they were working on the Oslo Agreement, they let Israel decide how the prisoners would be released. I think they shouldn’t have agreed. Even our leadership told us it had been wrong about this issue.”

Rizq Salah, who murdered IDF soldier Guy Friedman with an explosive device in 1990, has an even stronger opinion: “In the beginning, we felt betrayed by the Palestinian leadership in the West Bank. We got a copy of the Oslo Agreement and failed to find a single article in it about us. There were 15,000 prisoners like us in Israeli jails, and not a single segment about us. I nearly went wild.”

Daily schedule: Roll-calls, walks and cigarettes

The conversations with Ynet shed light on the security prisoners’ life behind bars. The prison has a regular daily routine: At 6:30am, there is an hour-long roll-call during which the prisoners must stand while the wardens visit their cells. Later, a limited number of inmates is allowed to go out to the prison yard for a non-compulsory workout. Then they return to their cells for a shower and a meal.

Later, the prisoners are allowed to take a walk or sit in the yard if they want to. Then the cells open up for a limited period of time, and the inmates are free to visit their friends in the other cells in the wing.

The wardens check the cells to rule out any attempts to escape or saw through the bars, etc. At this time, the prisoners are removed from the examined cell.

At 12pm, the inmates must return to their cells for the afternoon roll-call. Once it is over, the cells reopen and assigned prisoners clean the wing and the yard and dispose of the trash. They also hand out food to the other inmates in their cells. Surprisingly, the prisoners say they enjoyed being on duty, as they considered it a routine-breaking activity that helped them pass the time more efficiently.

Between 1-5pm, the prisoners are permitted to take a second walk in the yard, in several rounds. They return to their cells in the afternoon hours, and the evening roll-call is held at 7pm. In between, they have dinner. After the evening roll-call, the cells are locked until the morning, and the inmates are free to watch television.

There is no official lights-out policy, and it’s basically up to the inmates. Some say they used to go to sleep relatively early, at around 10pm, while others liked to stay up until the middle of the night.

The number of prisoners per cell varies between the different prisons. At the Hadarim Prison, for example, there are three inmates per cell, while at the rest of the prisoners there are eight to 10. Smoking is permitted in the cells without any restrictions.

According to the prisoners’ rating of the different jails, the Ashkelon Prison is the worst while the Ramon Prison is the best. Most interviewees described the infrastructure at the old-fashioned Ashkelon Prison as very poor.

‘We broke his hand’

The security prisoners created their own set of strict rules for prison conduct. An inmate who commits an “offense” goes on trial in an internal “court” and is punished according to the severity of his act. The punishment system is secret and the prisoners do everything in their power to prevent the Israel Prison Service from finding out about it. Issa Abed Rabbo agreed to give us a rare peek into what is considered taboo among the prisoners.

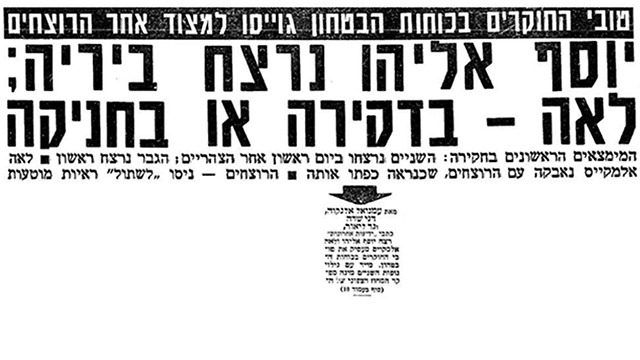

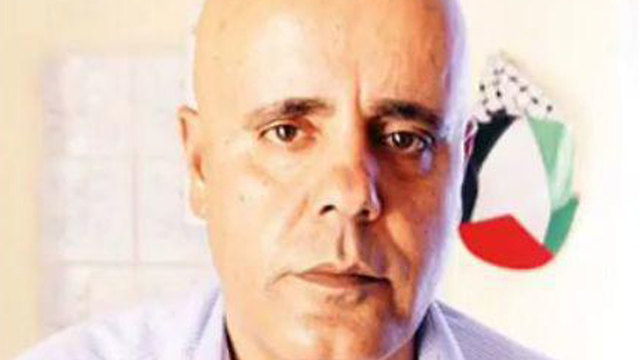

Abed Rabbo, who murdered Revital Seri and Ron Levi near Bethlehem in 1984 and was considered one of Fatah’s top prisoners, lives in the Dheisheh Refugee Camp.

“There are committees in every prison,” he says in the interview. “Each wing has a committee. In each cell, there are one or two people in charge whose job is to solve problems. If there are problems between two people, they are raised and discussed. The one who is found to be at fault is punished. The punishment is decided by the small committee, and the senior committee signs and approves it.”

What are the punishments?

“If someone hit someone else, he will be hit on the hand 20 times and will be denied the right to buy from the prison canteen.”

What was the most serious offense committed by a prisoner?

“One prisoner cut another prisoner’s face with a razor.”

How was he punished?

“We broke his hand. He did the worst thing possible as far as we were concerned, raising a knife on a friend.”

How do you break a person’s hand?

“Every bunk bed has an iron ladder. You put his hand between the rungs of the ladder, and then one inmate kicks his hand and it breaks.”

That’s brutal.

“Yes, it’s hard, but he did something very serious.”

How is a trial conducted?

“It’s begins very fast. Because of the prison management, you can’t wait patiently. If something like that happens, the committee starts by questioning the stabbed inmate and then going to the other guy and asking him why he did it. The punishment will be quick. The trial is held on the spot. They don’t wait for the prison management.”

‘Snitches are sometimes killed’

The inmates know that heavy punishments like a broken hand can’t be concealed from the prison management. The injured prisoners are taken to the hospital, and the prison’s intelligence officer tries to figure out what happened.

According to Abed Rabbo, there is a code of silence between the security prisoners about the internal punishment system, which must not be violated. “If he is a good guy, he wouldn't talk,” he says. “He’d say his hand broke because he fell out of bed. He’d never tell. Some people did tell the management what had happened to them. Those who discuss it with the management don’t come back to us.”

Other punishments imposed by prisoners on fellow inmates include cleaning toilets and rooms and refraining from smoking for a certain period of time.

The security prisoners also deal with the issue of collaborators among the inmates—those who provide information on the things taking place inside the wings and the cells, likely in exchange for different perks. They are referred to as “aSaafiir” (birds).

“We manage our life in jail very well. We know what every person is doing, even what he drinks,” Abed Rabbo adds. “We have good friends in every cell, and they write down the exact things every person in the cell is doing. We write down everything and send the report to the security chief at the Palestinian apparatuses. That’s how we know what every person is doing.”

And what happens if you suspect someone is an “uSfuur” (bird)?

“Sometimes we interrogate him, and sometimes, if it’s a prisoner who has a month or two left in jail, we send it to the Palestinian Authority and the apparatuses question him when he gets out.”

If you find an “uSfuur” in prison, do you punish him?

“Of course. There are lots of punishments. If he did small things, he gets an easy punishment. If he did something big, they would sometimes kill him.”

Let’s assume the management finds a cellphone during a search, and you suspect one of the prisoners tipped off an officer. Is it considered a serious offense?

“No, that’s a small thing. He will be suspended from the organization for a limited period of time and will be punished by being beaten up or something else.”

10 minutes a week with a smuggled phone

Phones smuggled into jail have become increasingly important for the prisoners over the past 15 years. They are willing to pay a lot of money for a smuggled cellphone, which serves as their connection to the outside world, whether for conversations with family members or for coordination purposes between the prisoners’ leaderships in the different prisons.

A smuggled cellphone, they say, costs NIS 35,000-70,000, and the price increases in accordance with the device’s technological abilities. Sometimes, especially among Hamas prisoners, these phones are used for guiding terror attacks.

“There are two or three cellphones in every wing,” says Mudqaq Salah, who murdered Israel Tenenbaum in Netanya in 1993. “Everyone knows about it, and it’s shared by everyone. Once a week, during the weekend, you are entitled to 10 minutes on the phone. There are phones with cameras, so you can talk and see your family.”

Abed Rabbo admits some prisoners used cellphones to carry out terror attacks. “I’ll tell you honestly, there were prisoners who misused the phones. Wanting to kidnap, wanting to kill. But most prisoners used the cellphones to talk to their families. I treated the phone in my cell like gold. I used it only to talk to my mother.

“If we know there’s a collaborator in the cell, we say the phone has been hidden in a certain spot so he will inform the management. And if they come looking, the phone is in an entirely different place.”

Abed Rabbo says the prison management knows there are smuggled phones in the cells, but it usually prefers to turn a blind eye to maintain a calm atmosphere in the prison.