New Polish remembrance day: Manipulation or moral message?

Op-ed: The Polish government’s attempt to emphasize the issue of Poles who saved Jews can be seen as a trick aimed at clearing the Poles’ conscience. On the other hand, the efforts to glorify the rescue of Jews during the Holocaust can also be seen as a source of great national pride and a message to the young generation.

The date—March 24—was selected to mark the day in 1944 in which the Nazis murdered eight members of the Ulma family, two adults and six children, who hid eight Jews in their home. Those Jews were also murdered. They were all turned over to the Germans by a polish policeman.

In 1995, Yad Vashem added the Ulma family to the Righteous Among the Nations list. The family lived in the village of Markowa in southeastern Poland, at the foot of the Carpathian Mountains. Before World War II, the village had 120 Jewish residents. About 30 of them survived the Holocaust after finding shelter (usually for money) with local peasant families.

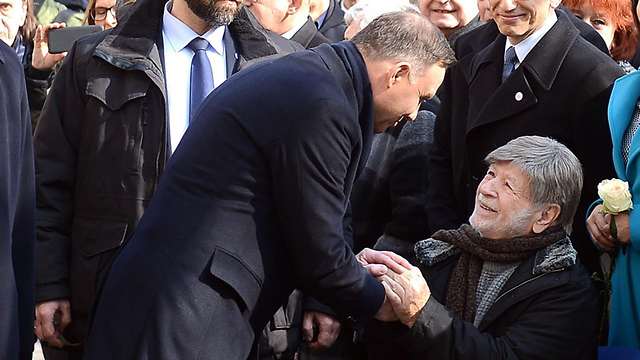

The Polish government, led by the nationalist-conservative Law and Justice party, inaugurated in Markowa in 2016 the Ulma Family Museum of Poles Saving Jews in World War II. The museum, which has a Hebrew-language website, was the center of the ceremonies and conferences marking rescue day. Independent Polish historians have criticized the museum display for being one-sided and ignoring the persecutions, extraditions and murders of Jews in the area.

The remembrance day for Poles who saved Jews was led by the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN), which is combination of a research institute, an archive and a legal practice. Among other things, IPN produced a video about the Polish acts of heroism in saving Jews, distributed learning material for schools and prepared a mobile exhibition about the Żegota organization, the Polish Council to Aid Jews, which operated as a secret arm of the Polish national resistance and the state’s army. The Polish postal company issued a special stamp with the portrait of Irena Sendler, a Polish woman who saved many Jewish children and was recognized as a Righteous Among the Nations.

Some 3.3 million Jews lived on Polish territory before World War II broke out; 50,000 of them survived the Holocaust. Half a million Jews lived in the capital of Warsaw; 98 percent of them were murdered in the Holocaust and in the revolt, and 2 percent survived. There was no other ghetto like the one the Nazis built in Warsaw in any other city in occupied Europe.

Jewish Canadian historian Gunnar S. Paulsson estimated in his controversial book “Secret City” that some 80,000 Poles in the Warsaw area had been directly or indirectly involved in aiding Jews. Many historians believe the number is radically exaggerated, and that “only several thousand noble and brave Poles” operated in occupied Warsaw, as Prof. Havi Dreifuss has stated.

Nearly 6,700 Poles have been recognized as Righteous Among the Nation, according to strict Yad Vashem criteria, including the condition of not taking any money or cash equivalents for the rescue. But since the reality in the days of the Nazi occupation in Poland was very complex, it’s impossible to make clear distinctions between humanitarian and material motives. The correct number of Poles who saved Jews is therefore higher, but it’s still far from the hundreds of thousands implied by the modern rewriters of Polish history.

Some 250,000 Jews who fled the ghettos, the trains and the death camps were turned over to the Nazis by Polish people, and thousands were murdered by their neighbors.

The Polish government’s attempt to emphasize the issue of Poles who saved Jews can be seen as a distraction and manipulation trick aimed at whitewashing and clearing the Poles’ conscience, presenting Poland as a victim of an international plot, mainly a German-Jewish one. On the other hand, Poland’s efforts to glorify the rescue of Jews during the Holocaust can be seen as a source of great national pride and a moral message to the young generation, a message of sacrificing yourself for your Jewish neighbor.

With all the justified criticism over the law against “slandering Poland,” over the regular replacement of museum directors, over the forgiveness towards anti-Semitic acts, we shouldn’t ignore the fact that 75 years after the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Poland is still mercilessly dealing with the open wounds of the Holocaust era and continuously engaging in national-moral self-examination. As far as Poland is concerned, as far as we’re concerned too, that past isn’t over and done with.