Jewish officer and liberator recounts Nazi horrors, elation of vengeance

A collection of letters donated by the family of a Jewish-American officer who took part in the liberation of several Nazi concentration camps during World War II depicts shock at witnessing full scale of Holocaust atrocities, as well as survivors' need for retribution.

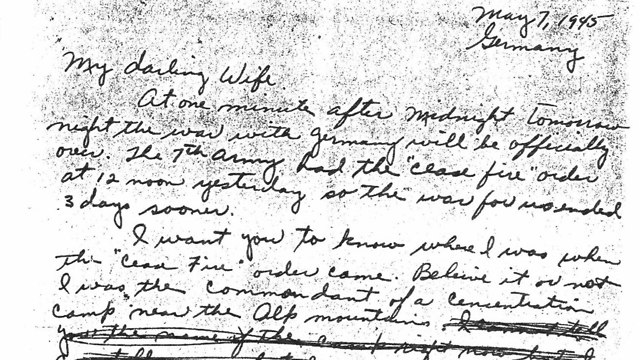

May 7, 1945—the day before the surrender of Nazi Germany took effect. The unit of Dr. Alvin Weinstein, a Jewish officer who serves as a doctor in the American army, recently liberated the Nazi concentration camps of Dachau, Liebenau and Laufen.

Weinstein, who commanded the last two days after the liberation, wrote to his wife in New Jersey and described the nightmarish scenes he witnessed: "My dear, no one will believe what I saw on the last day of the war. I know you will not believe me, my dear, so I took pictures of everything and when I get home I'll show you."

Following his death last year, Weinstein's letters and pictures were donated in February by his family to the archives of the Massuah Institute for Holocaust Studies in Tel Yitzhak. These unique materials document the first days after liberation of the three camps and are not found in any other collection around the world.

"Tomorrow night, one minute after midnight, the war with Germany will officially end," Weinstein began in his letter to his wife. "I want you to know where I was when the cease-fire order was issued.

"Believe it or not, I was the commander of a concentration camp near the Alps."

Weinstein did not fail to describe the physical condition of the prisoners he met, and said that some of them survived the death marches, but not without harm.

"I saw 243 starved, tortured and disease-stricken bodies that were once human beings. 170 of them were Polish Jews who were the only survivors of the 1,600 who had left the Buchenwald concentration camp.

"They walked 440km barefoot for 28 days. They were given five potatoes a day and no water. Anyone who fell or received food from civilians was shot dead by SS soldiers.

"When they reached their new prison, everyone was crammed into barracks together with 73 Russians and Poles in a similar situation. The smell in the shacks made everyone who entered them vomit or at least gag."

Weinstein was appointed commander of the Liebenau camp, which he described as an assortment of "huts without a sewage system or ventilation." A medical doctor, he noted the survivors' physical condition in clear, even clinical detail.

"The men had straw mattresses covered with lice and they were barefoot and half naked, many of them suffering from high fever and hallucinations. I'm sure many of them were infected with typhoid," he attested.

"When the American soldiers arrived, they cheered and cried as though the Messiah had finally arrived. From a nearby camp, packages were sent to them from the American Red Cross and they enjoyed delicacies they had not known since the war began.

"The packages contained cigarettes and chocolates and meat that they could not chew because of their swollen tongues. The things we think of as ordinary were for them a godsend."

'They beat those Hitlerites until they nearly died'

Dr. Weinstein described not only the physical condition of the liberated survivors, but also the emotional state and moods that included more than anything a strong desire to take revenge on the Nazi guards at the camp.

In one incident, Weinstein said, one of the battalion commanders he served with brought two German soldiers who were without uniforms to "the barracks with those tortured souls" and told them that they were members of an SS unit.

"Suddenly these men's strength returned to them and they beat those Hitlerites until they nearly died," he wrote.

"We went inside and stopped them (from killing the two) and put the beaten Nazis on a jeep that took them outside the camp. They were so scared they jumped out of the jeep and tried to run but a guard killed them both.

"When the prisoners heard the shots, they cheered and begged us to bring them more men. They no longer wanted food, a shower or a bed—only more SS men."

Weinstein, like many others at the time, did not truly believe the stories about the concentration camps, thinking it was more exaggeration then reality. What he saw, though, convinced him otherwise.

"I, too, did not believe my eyes. I, too, thought it was propaganda. But now I know it was all true," he admitted.

"Every SS man should be tormented the same way they tortured these poor refugees. Those people—whose greatest sin was being born into a particular religion—should have the right to try and judge these sadistic torturers who murdered four and a half million people of their religion."

Towards the end of the letter, Weinstein spoke of his feelings as a Jewish officer who commanded the release and rescue of his people, the survivors of unimaginable horrors.

"My heart is too full," he wrote. "I fought hard in this war, but as a Jew I fought for my Jewish brethren as well as my country, and on the last day of the war I managed to free 160 of these miserable people.

"My mission in this war has been accomplished. My country defeated the enemy armies and I managed to liberate some of my people. I ask for nothing more."

"Darling, I'll write more tomorrow. I can think of nothing but the misery I saw," he concluded.

'He gave me his Yellow Patch'

The collection of letters handed by Weinstein's family also contained another letter by a man named Murray Eisenstein of Florida, an infantry sergeant from Weinstein's unit, written some 40 years after the end of the war. In it, Eisenstein depicted a chance meeting with a Jewish survivor during the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp—a moment he since considered to be the "apex point" of his life."We brought down the gate and went into the concentration camp, just in front of us were thousands of people in these striped, grotesque uniforms," he recounted, saying saw in the camp small, shoddy buildings and iron cars on a railroad track at the end of the camp.

He noted they later learned the iron cars contained piles of corpses thrown together with dying people.

"A lot of prisoners approached us and asked for rifles so that they could kill the guards who remained in the camp," he echoed Weinstein's testimony. "Many of us had spare weapons that we agreed to give them, and they used them to kill the guards, those who were not the commanders, who had already managed to escape."

Afterwards, Eisenstein wrote, he "saw an elderly man sitting and rocking back and forth as if in prayer or mourning.

"I walked toward him and he asked in Yiddish who I was. I replied that I was a Jewish-American soldier. The man cried and said, 'Everything is over, everything is lost.'

"I put my hand in my pocket and remembered that last night we were chasing SS forces, killing them and rummaging through their pockets. I had 15,000 to 20,000 German Marks in my coat. I took the money out and tried to put it in the pocket of this prisoner's uniform. He looked at me and said in Yiddish, 'I cannot accept this gift ... it's not proper ... I have nothing to give you in return, pointing at his yellow Star of David badge on his uniform."

Eisenstein made him a deal—the money he took from the slain SS soldiers for his Yellow Star. "He gave it to me and it's been in my possession for the past 40 years," he said.

"As an infantry sergeant, I had many experiences. But I must point out that when that lost soul told me that he could not accept my gift, because he had nothing to give in return, I broke down completely. That moment of human emotional expression will forever remain the apex point of my life. I always hoped that my gift was useful and gave this man a chance to live, maybe in Israel, where he could live a normal life again."

Massua Director-General Aya Ben Naftali stressed the significance of Weinstein's collection, as it is not only testimony by a Jewish officer who liberated Nazi concentration camps, but also a look through the eyes of a doctor, who took note of "both the physical condition of the survivors and their mental state."

"There are hardly any references to this in writing," she noted. "It really describes the day the war ended and the situation of the Jewish people with great empathy."