It’s good to live for our country

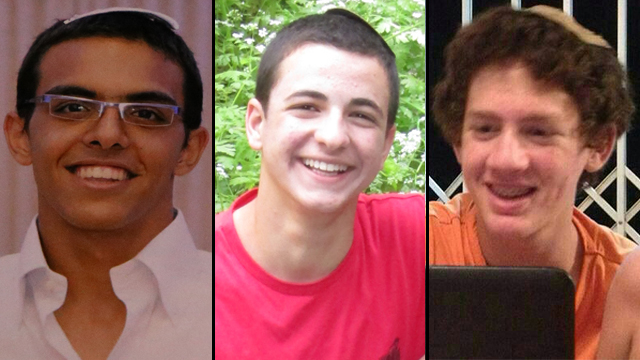

Op-ed: Racheli Frenkel, whose son Naftali was kidnapped and murdered with two other teens in June 2014, explains what Memorial Day means to her: ‘Our memorial days have never been a veneration of the dead. We mention our loved ones, the joy and the smiles, so they will keep living among us. Our mission is to make life better, thanks to them.’

Memorial Day has hardly changed for me since the murder. Life has changed, and there are special days too—the birthday, the day of the kidnapping and the murder, the burial day—but my Memorial Day has hardly changed. I don’t feel a stronger connection to this day now. It has always been my Memorial Day.

I once heard about a support group for parents who lost their children in a mass-casualty incident. At one point, they were asked what was on their horizon, what they wished for themselves now. One of the parents had the audacity to say, “My goal is that my family will have an even better life than before the disaster.” Within the sea of pain in the group, this wish almost seems arrogant. The truth is that one can wonder and fail to understand, and one who is familiar with the burden of the yearning and the pain can doubt and question, but this aspiration is completely appropriate!

In fact, we know that happiness isn’t the result of continuous pleasure, but of meaning, activity, gratitude, friendly relations and family ties. It doesn’t happen on its own and it doesn’t happen without a choice and effort, but we can definitely imagine the lineup of these elements of goodness building up and intensifying in the gentle mending processes that form after a disaster.

In one of her studies, sociologist Brené Brown asked dozens of people who had experienced bereavement what could be done for them. She repeatedly heard the following answer from the family members: When I see you cherish the blessings in your lives, it helps me heal. When you respect what you have, you respect what we have lost.

People don’t yearn for the highlights of their life, and they don’t even yearn for the events they won’t get to experience with their loved one. They endlessly miss the ordinary days, the little moments they had almost despised.

Once, after an event focusing on “Brother's Keeper” (the IDF search operation to find kidnapped teens Naftali Frenkel, Gil-Ad Shaer and Eyal Yifrah), I was approached by a person I didn’t know, who asked me: “Which one of you said that thing about the Priestly Blessing? I have to thank him.”

I knew what he was talking about. The three teens’ fathers were asked in a radio interview what they missed the most. Ofir, Gil-Ad’s father, talked about the custom of letting the children gather under the prayer shawl during the Priestly Blessing and about Gil-Ad’s painfully tangible absence in those moments.

The man standing in front of me wasn’t referring to the heartbreaking aspect of that story, but to the celebration of life. He was given a gift—he always used to bless his own children that way, but those moments just passed by him. He nearly missed them. Now, he cherished them very much. They became moments of gratitude and magic. The essence of life. This applies to one’s personal life and it applies to the entire society. The skill is to raise the price of the good, and in light of the price—to make life even better.

My Memorial Day has hardly changed. It has always been mine, ours, the closest thing to sanctity that can be created by a secular calendar. It has never been perceived as a gesture towards the bereaved family, as a show of respect and goodwill, a gesture towards the victim. It’s coming together around the loss we are all experiencing. One doesn’t have to lose a close relative, God forbid, to feel that this date is part of Israel’s personal and familial calendar.

But our memorial days have never been a veneration of the dead. This isn’t a culture of martyrs. We will always favor, appreciate and celebrate life over death. It is good to live for our country, it is good to live. It is good to raise the price of life.

When we gather, with respect and yearning, around the names and faces we knew, it’s not an addiction to pain. It’s not a macabre day of mourning. It’s a day of renewing the commitment, of reviving the alliance.

We mention our loved ones, the joy and the smiles, so they will keep living among us. Our mission is to make life here better, thanks to them. Their friendship is our challenge, their solidarity has become our responsibility: To incorporate the memory of love into caring, to incorporate the passion into respectful disagreements. To turn the self-sacrifice into further closeness, and to turn the memory into life.

Racheli Frenkel is the mother of Naftali Frenkel, one of the three teens who were kidnapped and murdered on June 12, 2014.