The Jews-by-choice of San Nicandro, Italy

Hidden away in a remote village in southern Italy stands a small and unique synagogue that is virtually under female control. It all began almost a century ago, when ‘prophet’ Donato Manduzio fell in love with Judaism and gathered a community of believers. After dozens of residents converted and made aliyah, those left behind were mostly women who married local non-Jews. Together, they keep celebrating Shabbat and festivals, eating exclusively kosher food and studying Torah. ‘Every day when I pray,’ says Grazia Sochi, ‘I dream I’m at the Western Wall in Jerusalem.’

The women of the community maintain a flourishing Jewish lifestyle in the heart of a devout Catholic area. In most cases, their husbands are Catholics and many of them are not considered Jewish according to Jewish law—but this does not prevent them from feeling that they are proud Jews.

The unique synagogue is located in a small building which the women, many of whom are engaged in agriculture, bought in 1994 with money they had collected on their own, lira by lira, and without any external help, so that they would have a place to pray. “We would tell our husbands that the price of the dress we bought was a bit more expensive, and we would save the difference in money for the purchase of the synagogue,” one says with a wry smile.

We came to visit the village together with Michael Freund, the founder and chairman of Shavei Israel—an international Jewish organization based in Jerusalem. Its goal is to reach out to communities around the world with Jewish ancestry as well as those who want to connect with the Jewish people. Rabbi Pinhas Punturello, Shavei Israel’s emissary to Italy, also joined us.

The women of the community were very moved by their visit, and they received the guests from Israel with songs and hymns in Hebrew and Italian. We were welcomed into the home of Lucia Guellano Leone, 50, one of the dominant women in the community. Her husband, Matteo, is a former Catholic who underwent conversion with her, and now works as a kosher supervisor at a cracker factory in the port city of Bari.

Inside the Holy Ark in the local synagogue there is, among other things, a particularly old Torah scroll that is 300 to 400 years old. Next to it is a Megillat Esther, the Book of Esther that is read on the holiday of Purim, which the women of the community had prepared many years ago—although it was clear to them that according to Jewish law it was invalid. Two years ago, they received a kosher scroll, which is used for reading on the festival, but they refuse to discard the non-kosher scroll, which for them serves as a symbol.

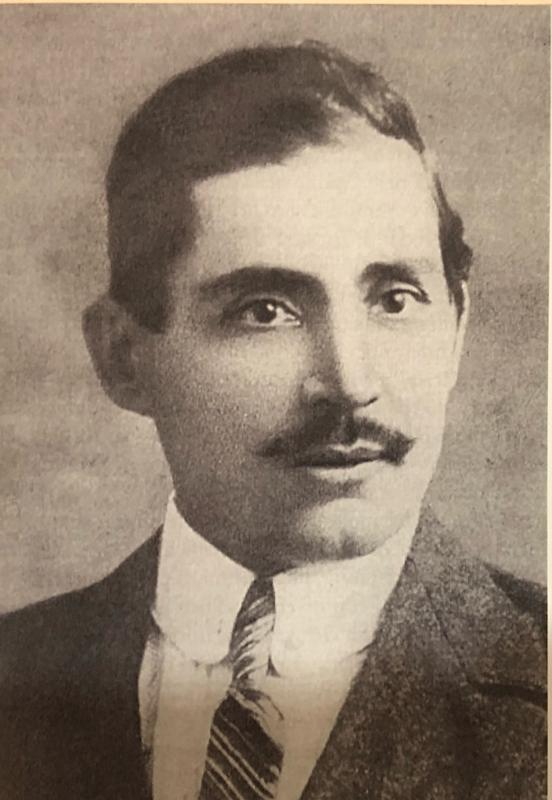

The story of the community of converts from San Nicandro, which could easily become a Hollywood movie, begins in the first World War. Donato Manduzio (1885-1948) was a farmer’s son who had never set foot in a school. During World War I, he was drafted into the army and wounded, and then hospitalized in a military hospital in Pisa with his legs paralyzed. In the bed next to him lay a wounded man who taught him to read and write, and so he began to read books.

When Manduzio returned to San Nicandro, he read a great deal of Italian literature and became a healer who brewed potions. After undergoing a “divine revelation” in the middle of the night, he began to study the Old Testament and came to the conclusion that Judaism is the true religion. He began observing Shabbat and gradually other commandments. He conveyed his new teachings to his followers, and established the San Nicandro Jewish community, which at its height numbered 80 people.

Sometime afterward, a merchant who happened upon the village found himself in the midst of a conversation between Manduzio and one of his followers, who were discussing the Book of Psalms. The merchant asked Manduzio if he was an evangelical, and Manduzio replied: “No, we are the people of God” ("Popolo di Dio”).

When the merchant told him that there were thousands of Jews living in Rome, Milan, and Florence, Manduzio was stunned. He was convinced that the people of Israel he had read about in the Old Testament were extinct and no longer existed. He asked the merchant to give him the addresses of the Jewish communities and immediately sent them letters. After a lengthy exchange of correspondence, the Jewish community of Rome concluded that the San Nicandro community was serious and worthy of being converted.

The Chief Rabbi of Rome dispatched a messenger to visit the Mityahadim, or “Jews-by-choice” —as the Italian Jewish community called them—and on that visit the village’s first synagogue was dedicated and the community received prayer shawls, a menorah and several other religious articles.

Jeeps with Star of David

Today, there are about 50 people living in the village who continue to maintain a Jewish lifestyle. They observe Shabbat, perform public prayers on Shabbat and Jewish holidays in Hebrew and in Italian, and consider themselves Jews in every way.The Jewish women of San Nicandro eat kosher food, which they prepare themselves. They even make kosher cheese on their own under supervision. On Sukkot, they erect a large sukkah, organize joint meals on festivals, and every Friday they make a communal Kiddush and Shabbat meal. They make sure to eat only kosher meat, which is brought from Rome, separate meat and dairy, bake their own challahs and of course light Shabbat candles.

The synagogue compound has a screen, which they use to connect to a virtual class on-line with Italian rabbis in order to study Torah. There is a Beit Midrash, which also serves as a museum of the San Nicandro community. On the wall are historical photographs that describe the life of the community from the days of the prophet Manduzio until the present. Among the pictures are children dressed up in costume on Purim, lighting Hanukkah candles, dancing with a Torah scroll and celebrating Israel's Independence Day, which the community in the village marks every year.

The small Jewish community in the village has only eight children, and the women fear that there will be no Jews left in San Nicandro in the future.

The small and well-kept synagogue is located on a central street in the village. There are about 30 people praying on Friday night and about 40 on Shabbat, most of them women. The prayer includes melodies and fragments of poetry. The morning prayer lasts four hours, part in Hebrew and partly in Italian, and the Shabbat service in the synagogue is the center of life for the Jews of the village.

“The Jews of San Nicandro are a unique phenomenon. It is the first time in the modern era in Europe that an entire group of people formally embraced Judaism,” says Shavei Israel Chairman Michael Freund.

“Manduzio and his followers,” Freund says, “discovered the truth of Judaism entirely by themselves and without any external prompting. Despite the rise of fascism and hatred towards Jews at that time, they adopted a Jewish lifestyle with courage and determination and did not give up even after Mussolini decreed the racial laws against the Jews in 1938. They see themselves as spiritually connected with the Jewish people and the religion of Moses and Israel.”

The racial laws against the Jews of Italy were not applied against Manduzio and his followers, due to their Italian Catholic origin, despite their insistence on telling Italian fascist policemen, and later the German Nazi soldiers who entered the village, that they were Jews. Luckily, no one believed them. In 1943, Manduzio quarreled with one of the fascists in the village, who threatened to go to the police the next day and ask to arrest all the Jews. The legend in the community relates that Manduzio, who engaged in Kabbalah, told him: “You will not arrive tomorrow.” A few hours later, the man fell and died.

In October of that year, the British army captured the village from the Germans. Several jeeps belonging to the Jewish Brigade, a group of Jewish fighters from the Land of Israel who served in the British Army during World War II, passed through San Nicandro and they were emblazoned with the Star of David. Manduzio’s followers saw the jeeps pass but did not manage to stop them. They ran to tell Manduzio about the encounter and he decided to paint a flag with a Star of David on a blue background and hang it on his house—in case the jeeps passed by again.

And so it was. The Jewish officers from Israel, who did not know a word in Italian, were astonished to meet Jewish farmers in the remote village. The soldiers of the Jewish Brigade spoke to Manduzio and heard his story. They decided to call him “the Prophet,” a nickname that would accompany him later on.

Members of the Jewish Brigade urged the people of San Nicandro to immigrate to Israel, telling them a Jew’s place was in the Land of Israel. In 1946, the rabbinate in Rome converted the community. In the years 1947-1949, 74 members of the San Nicandro community immigrated to Israel on ships that brought Holocaust survivors from Europe. They settled in three communities: Ashkelon, Bat Yam, and Safed.

The “prophet” Manduzio objected to their emigration on the grounds that the role of the community was to be a light unto the nations. He remained in the village with his wife and three other women who were married to Catholics.

A few months prior to the establishment of the State of Israel, Manduzio passed away and was buried in the Jewish section of the small cemetery in San Nicandro. On his grave is a Star of David and the inscription: “Here is buried he who lived under the delusion of worshipping foreign gods until 1930, but on August 11 of that year, by Divine inspiration, called himself Levi, proclaimed the unity of God and the observance of the Sabbath.”

6,800 euros for a 'Shabbat clock'

In recent years, 14 of the 50 members of the San Nicandro community have undergone conversion by an Italian rabbinical court, thanks in large measure to the efforts of the late Rabbi Giuseppe Laras, one of Italy’s most prominent rabbis, and Shavei Israel. The rest of the women have encountered difficulties in undergoing the complex conversion process, which requires undertaking a long trip and residing in one of the larger Jewish communities in Italy, such as Rome or Milan. Apart from the fact that this will disconnect them from the village and their fields, the requirement that they convert to be officially recognized as Jews offends some of them.“The fact that they do not officially recognize me does not change the fact that I'm Jewish,” says Grazia Casavecchia, a member of the community. "I study Torah without calling it a conversion process because I am already Jewish. When I follow the commandments and maintain a Jewish lifestyle it gives me a good feeling and I don’t care if I do not have a formal stamp of approval. It is like discovering one day that you are an adopted daughter of Judaism, and it's hard to accept it.”

Lucia Leone, who specializes in growing tomatoes, peppers and olives, and also makes excellent olive oil, describes the insult she felt before she completed her conversion: “I cried when I heard from the rabbis that I was not Jewish according to halacha. How can it be? I am a descendant of Manduzio’s followers and I also have a Jewish family living for many years in Israel.”

Lucia Zorro, 50, who is married like most women in the community to a Catholic man, boasts that, “my children live as Jews, but when they grew up they moved away from it a little. The amazing thing is that my husband got angry at them and asked them to respect their mother and continue to live a Jewish life.”

Her husband, Nazzario, stopped eating pork two years ago and refrains from going to a cafe or restaurant on Shabbat. The women, though, do not pressure the husbands to convert: “There is mutual respect here,” explain the men and women alike.

Thus, for example, the Catholic husband of Grazia Sochi, one of the community activists, prepared a menorah and a Star of David at his workshop and then placed them in their field. She boasts that he also paid 6,800 euros to bring into the house a “smart” clock system that operates all the electricity in an automated fashion, including lighting and shutters, in order to observe Shabbat properly.

“My husband even encourages our sons to go to synagogue with me,” she says. “He respects me very much and at home we celebrate only Jewish holidays. We do not celebrate any Catholic holidays, but my husband does not want to convert and I respect him.”

The San Nicandro community in Israel continues to maintain contact with the “mother community” in Italy and their members come for visits and vacations in the summer. According to them, they did not experience any problems of anti-Semitism, and the mayor even named a square in the town after Manduzio.

The women of San Nicandro consider the possibility of immigrating to Israel, but they claim that without conversion it is unrealistic. Their economic situation also makes it difficult for many to visit Israel, but that does not stop them from dreaming about the Promised Land.

“Every day when I pray, I close my eyes and imagine myself at the Western Wall in Jerusalem,” says Grazia with glistening eyes. And who knows, perhaps her prayer will soon come true. Michael Freund of Shavei Israel says he hopes to organize a trip to Israel for San Nicandro’s determined “Jews-by-choice” this summer, enabling them at last to realize their dream.