The United Nations agency dealing with Palestinian refugees may not be able to open schools for half a million children because it has run out of money since the United States cut its funding, UN officials say.

UNRWA, which runs more than 700 schools for Palestinian refugees, already faces what it described as a "very tense" situation in Gaza after job cuts drew protests by its own employees, leaving some senior staff unable to work in their offices.

Some fear for the survival of the agency, which this month must decide whether it can open its network of schools across Gaza, the West Bank, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon for the coming academic year.

"We are running on empty. We simply don't have enough money to pay 22,000 teachers who in 711 schools provide a daily education for over half a million children," said UNRWA spokesman Chris Gunness, who described the situation as "catastrophic" and unprecedented.

UN officials say that aid cuts by the United States, the single largest donor to UNRWA, were a major cause of the crisis.

In January, US President Donald Trump said he would scale back aid to the Palestinians unless they cooperate with his plans to revive peacemaking with Israel. Those peace efforts stalled in 2014.

"The actions that we are now seeing are consequences of the decision by the Trump administration to withhold $305 million for UNRWA this year, so whether it is political or not it has catastrophic implications and consequences for us on the ground," said Gunness.

Worry at schools

Palestinian families, children and teachers said they were worried about whether schools will open at the end of August.

In the West Bank, Reem Nakhla's children attend an UNRWA school in Jalazone refugee camp. In June staff and pupils were thrilled to be visited by Britain's Prince William during his tour of Israel and the West Bank. But now there is confusion outside the school gates.

"Of course I am worried, I think about where should I send them," said Nakhla. "The UNRWA school is a big help to people," she added. "Our situation in the camp is very difficult."

UNRWA was founded in 1949 in the aftermath of the War of Independece.

That conflict saw 700,000 Palestinians forced to leave their homes or flee. UNRWA now helps around 5 million Palestinian refugees, who include descendants of those displaced by the fighting nearly 70 years ago.

Funded almost entirely by voluntary contributions from UN member states, the United States has long been its largest donor. But officials say that after the Trump administration slashed its contribution, UNRWA now needs more than $200 million from other donors to cover its deficit.

In January Trump tweeted "we pay the Palestinians HUNDRED OF MILLIONS OF DOLLARS a year and get no appreciation or respect. They don't even want to negotiate a long overdue peace treaty with Israel." The US State Department has said the agency needed to make unspecified reforms.

Israel has accused UNRWA of favoring Palestinians, and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu welcomed Trump's decision to cut funding. "This is how to rid the world of UNRWA and deal with genuine refugee problems, to the extent that such remain," he said in January.

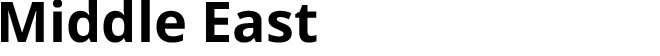

In Gaza, Amal Al-Batsh, deputy chairman of the union of Palestinian employees at UNRWA, feared that the United States was targeting UNRWA's existence "not as an institution but as a symbol and a witness to the issue of Palestinian refugees".

President Mahmoud Abbas's Western-backed Fatah faction said the Palestinian leader would seek donations for UNRWA at the upcoming UN General Assembly meeting in September.