Amar is a rare find in Israel's academia. He is a Mizrahi Jew who wears a black kippah, a Rabbi, but also a professor. For years he has been alone in this mission to find and preserve the cultural treasures of North Africa, while trying to interest various culture institutions in funding his research.

According to Amar, whereas there is a growing interest in Mizrahi music and cuisine, centuries-old spiritual treasures are being neglected. "Mimouna (a traditional Moroccan end-of-Passover celebration), and Mufleta (a Moroccan pastry - ed.) are nice to enjoy now—but the spiritual legacy will remain forever,” Amar said.

An expert in Medieval Hebrew Paleography, Amar is the chairman of the "Lights of the Jews of the Maghreb," an institution for the preservation of Moroccan Jewry heritage. According to the professor, the problematic relationship between Israeli academia and Sephardic literature and philosophy started back in the 80’

“There was an outrage following the publication of Kalman Katzenelson’s 1964 book entitled 'The Ashkenazi Revolution'”, he explained. According to the book, there are two peoples living in Israel: supreme Ashkenazim and inferior Sephardim, who should learn Yiddish in order to be considered 'cultured.'

“There was a great cry and then the Knesset decided to make a change. The Institute for Integration of Mizrahi Jewry Legacy was founded, and all the universities, who wanted in on the budgets, established research facilities," Amar added.

However, between 2006-2007, things began to change. “Limor Livnat, the education minister at the time, had decided to close the integration institution and the universities were out of incentives. Once a professor retired, his position was cancelled and only several courses were left," he elaborated.

There is no shortage of students, however. Amar says the majority of students come to study at the department after consulting with him about other subjects. “It ends there, unfortunately.They have nothing to do with it afterwards, Maghreb Jewry isn’t studied anywhere in universities," Amar lamented.

After the 2016 Biton Committee, which was supposed to encourage Mizrahi legacy in education, one would presume things are about to change. However, according to Amar, Culture and Sports Minister Miri Regev encourages Mizrahi popular culture alone. “We had high hopes of the Biton Committee, but nothing came out of it," he continued.

Professor Amar, one of the leading researchers in his field, is now retired. He travels to Morocco independently in order to find books and manuscripts from different communities—but it’s a one man mission.

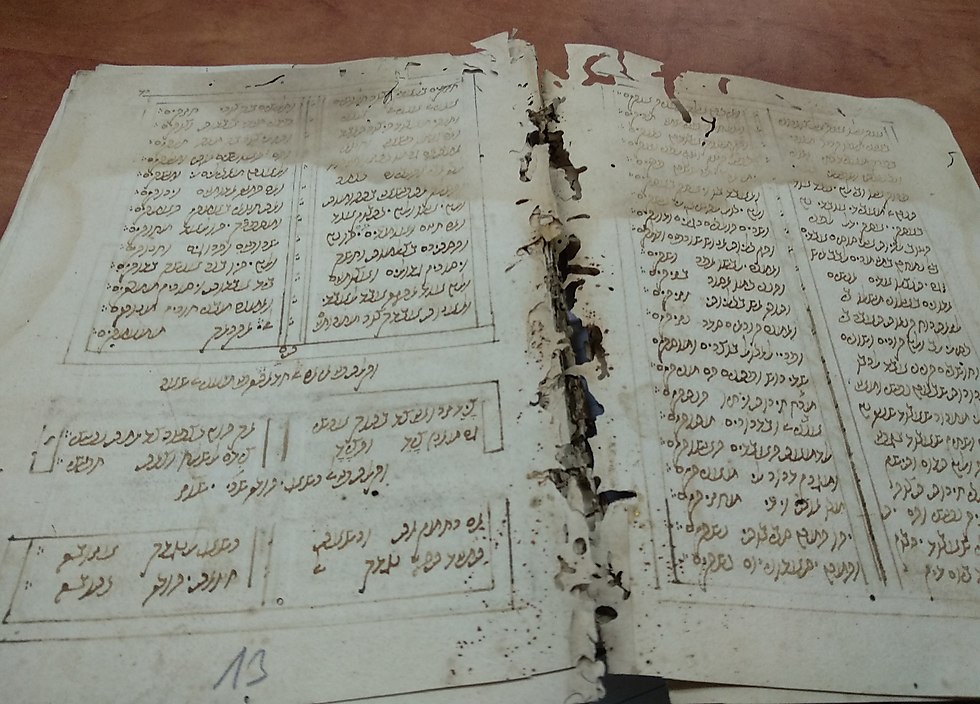

He showed me an ancient poetry book, written by a 15th-century Jewish diplomat named Avraham Ben Zimra, only a generation or two after the Alhambra Decree.“I found this by mistake, and intact! His poetry is amazing, and there are a lot of details here about one of the most important periods in history,” Amar exclaimed.

He found it while wandering around antique shops in Morroco. “Antique sellers collected things from abandoned Synagogues or from people who left the country. So I walked in and asked if they have anything that ‘belonged to Jews’. I asked for manuscripts, and the owner said ‘you won’t pay what I want for it’, but closed the shop and showed me the basement.

“In the basement this book was waiting for me, alongside Torah scrolls and inscriptions. Just by the writing I could tell it's very old, and I told him I’ll take it. He asked for $1000, an imaginary sum for Morocco in the 90’s. He said if I don’t take it, an American will come by and pay double the amount. What could I have done?" he went on to say.

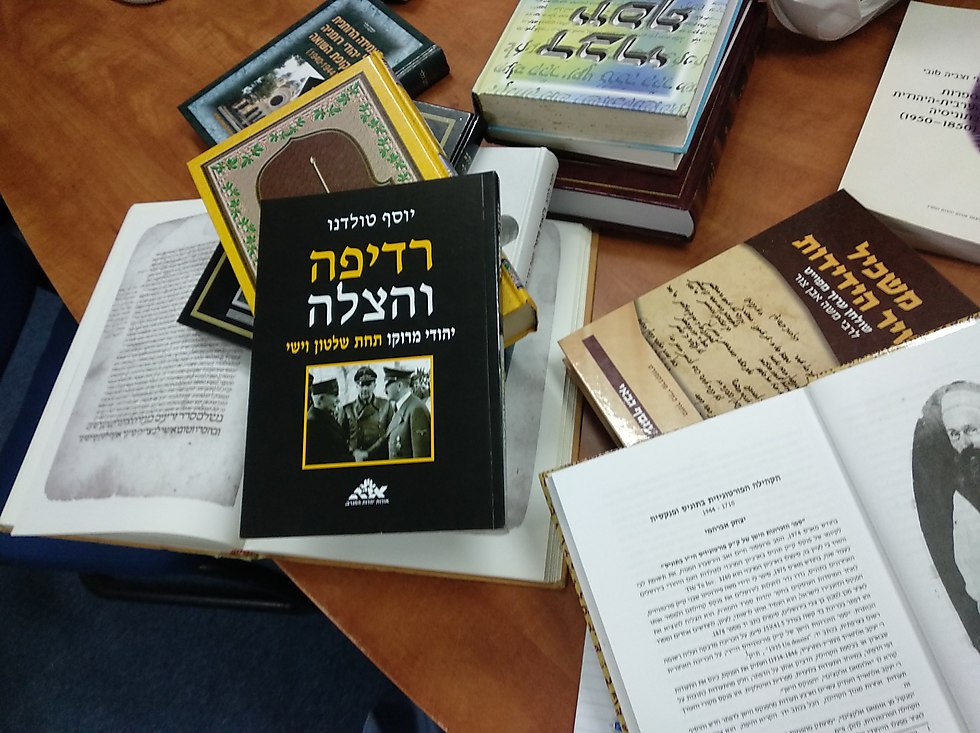

Among the texts Amar keeps in his archives are protocols from local Rabbinical Courts that tell the story of entire communities—stories of plagues, pogroms, hardship, philosophy and much more.

Amar’s life story is exceptional in itself. “In 1963 I arrived in Israel, and was studying in the famous Sephardic yeshiva Porat Yosef. The financial situation was difficult. I went to one of my teachers for advice, and he suggested I study to become a Rabbi," he elaborated.

Later on, Amar left the yeshiva and joined the IDF, where he served as a teacher. He continued to serve as a community Rabbi for a decade, until a friend introduced him to Professor Haim Ze'ev Hirschberg—the founder of North African Jewry research at Bar-Ilan University.

“Hirschberg asked, ‘do you have a high school diploma? How will you be accepted into university otherwise?’ I replied that I can read manuscripts of any kind. He pulled out a huge pile of papers from his drawer and asked me to translate them and write a few short texts, so I did," he said.

In 1975, Amar was accepted into university without a highs school diploma. “When I finished my BA I started my PhD immediately, and became a professor a few years after that— I, the yeshiva student, the Orthodox guy who knew nothing about academia.

"My dream is a school that will teach both Rabbis and researchers. We now started a small project in Jerusalem—we only accept Rabbis, and it’s a two-year program. We have two main goals—to teach students how to treat their public, and know the traditions of Sephardic Halachic ruling," Amar added excitedly.

“The young generation knows nothing of Sephardic ruling. They know the Lithuanian tradition,” he bemoaned.

However, Ashkenazi Rabbis also attend the program. “The change I see in how people think is amazing The Sephardic Rabbis knew how to handle problems that today are being dragged for years in the Rabbinate. They knew how to solve problems before they become problems, and how to rule in a way that emphasized Halacha. Today we are far from that kind of ruling,” he concluded.

.