Book can help Holocaust survivors reclaim property in Warsaw

Warsaw's 1939 land registry book could help Holocaust survivors reclaim thousands of properties confiscated under Nazi rule. We joined Yoram Sztykgold on their trip to the Polish capital for their sad journey to find his family’s lost property and found the fight for justice won't be easy.

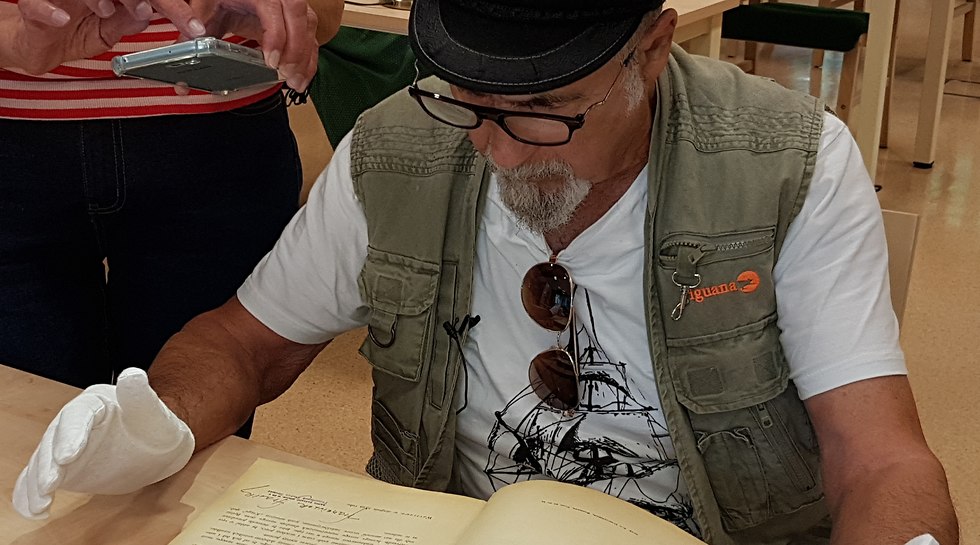

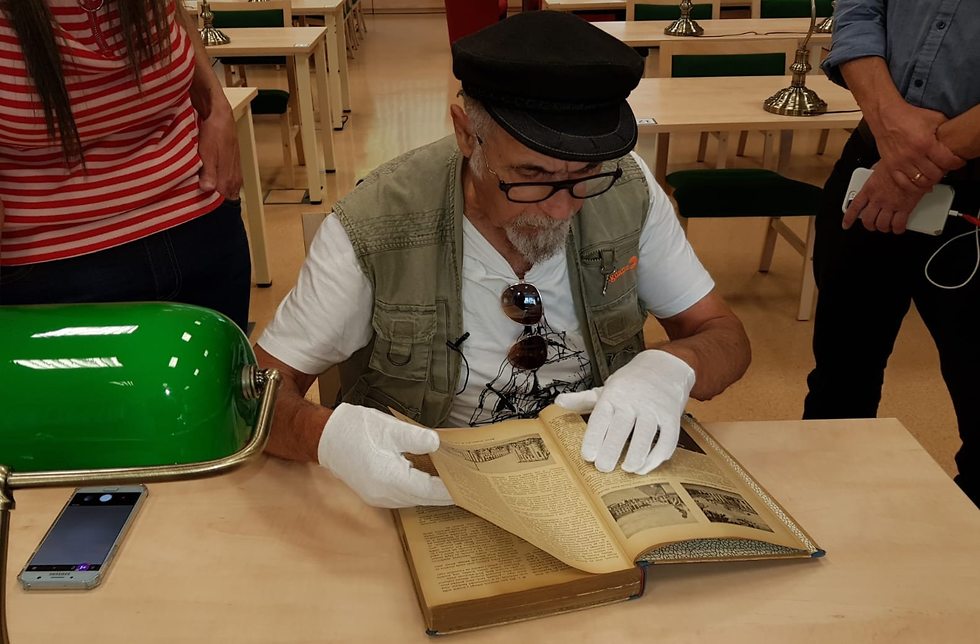

Yoram Sztykgold, 82, is one of those who dreamed of finding this book. For years, he tried to prove his ownership over the properties his family owned in Poland, which were confiscated during the war.

“I was probably the last boy to leave the Warsaw Ghetto, just a few days before the uprising,” he said, standing where there was once a big house right in the center of Warsaw, behind the large synagogue. Today it’s a municipal park with tall trees and public benches, filled with parents, children and elderly—some as old as Sztykgold.

He looks around, helpless. Nothing here reminds him of the city he knew as a child. Nothing is left of the place where his family home stood in the ghetto. “For me, there are two Warsaws,” he says. “There’s the Warsaw that is gone and will never return, and there’s the new Warsaw that came to life. They have nothing to do with each other.”

The Poles take their time

Yoram was born in September 1936 to a traditional Jewish family. His father, Mieczysław Moshe, was an engineer and owner of one of the biggest gas lamp factories in Europe of the time. His grandfather, Meir, was in real estate and owned multiple properties in Poland. He lived in a large house with servants, nannies and a cook. The family had at least 10 properties. And now, 73 years later, they want to reclaim them, or at least get restitution for the rightful heirs.In September 2016, the Warsaw municipality published a list of 2,613 addresses linked to open property claims, but without the homeowner names. Holocaust survivors had only six months to report to the Polish capital and reinstate their claims once the municipality published the announcement about their property in the local media. They later received three more months to prove ownership before the homes would be officially declared property of the Warsaw municipality or of the Polish Treasury.

So far, homeowners' details were only released for 211 of the properties, dozens every month. Some claim the bureaucracy and short deadlines are meant to make it difficult for the owners or heirs to claim the properties. The Polish authorities, however, claim it’s a way of preventing fraud.

What good is this list, if the heirs don’t know the addresses? This is where the World Jewish Restitution Organization (WJRO) comes to their aid. The organization created a database that allows survivors and heirs to track their assets by address, and learn whether they are entitled to proceed with claims that originated with the 1945 Warsaw Decree.

After the Holocaust, properties that were confiscated under German rule should have returned to their rightful owners. However, the Polish communist government nationalized properties, and so original owners were prevented from reclaiming their real estate assets. Poland, the home of 3.3 million Jews before the Holocaust, is the only one in Europe that doesn’t have a restitution of property law. The Warsaw case was unusual and gave hope to many.

A breakthrough was made when Logan Kleinwaks, a Jewish genealogist from Washington, managed to match addresses from the famous Warsaw book to the list of Warsaw homeowners from 1939-1940.

In 2014, Kleinwaks discovered that a Polish book seller is going to sell a copy of the homeowners' book at an auction in Krakow. He was going to attend but missed it, and the book was bought by the Polish Military Library for $3,000. The WJRO's computer database of Warsaw properties is based on the information in this book.

'For the kids and the grandkids'

We went on this journey with Yoram, his wife and his niece. It was a difficult journey for Yoram. One of the family's properties, which was listed under his grandfather's name since 1897, is now crossed by a street and houses a Polish kebab restaurant. Another one is 24 kilometers outside of Warsaw, in the city of Otvozk. A third is a massive property of 6,000 square meters that today is covered by forest and houses a huge villa.I suggest that Yoram enter the restaurant and introduce himself as the true owner. He’s worried: “We shouldn't cause provocation.” The Sztykgolds are now waiting for the Warsaw municipality to publish the list of properties from the book. Meanwhile, Yoram is trying to get his hands on documents that would prove his ownership. Apparently his mother filed a claim in 1945 and some documents do exist. The family hopes, but is skeptical that they can get all the paperwork done in six months in order to make the draconic deadline.

“It’s important for me, for my family, for my grandchildren, to get something for the properties we owned,” said Yoram. “Why? Because my children, and perhaps grandchildren, suffered through me. They deserve it. For me it doesn't matter, I’m 82. We’ll leave the historical justice to politicians.”

Yoram can’t forget the life in the ghetto, the hardships, the hunger. His grandparents, who were among the richest people in Warsaw, found themselves penniless.

“When I left the city, ten days before the uprising, there was no one left in the streets. The only ones left were those who had jobs, it was awfully quiet. My father got me and my mother fake IDs, and we decided to run, but at the last minute he didn't join us,” he recalled.

Yoram escaped with his mother, but they later parted ways and met again after the war. “I saw miserable people coming out of the fire. Disabled, burnt,” he said, when describing his return to Warsaw, which was in ruins. “My mother found me half dead, emotionally and physically devastated, exhausted, bloated with hunger. My recovery took months.”

Claims of property scams

“The Polish property restitution is a sensitive issue, and we want to change that,” said Konstanty Gebert, a Jewish journalist in the Gazeta Wyborcza, the country’s most important newspaper. “The reason for this is that people see property restitution as unfair, as it’s going to be funded off tax money. The Poles see themselves as victims of the Nazi and Communist regimes, and they feel it’s unfair for a few to get property and restitution from other victims.”“There is fear that if the property restitution is granted, there would be millions of Jewish claims that would empty the country's coffers,” Gebert went on to say.

In recent years, there have been several corruption scandals revolving around property restitution, including arrests of officials who were allegedly bribed by those who claimed properties. Poland's Deputy Minister of Justice Patrick Yaki, who is also the ruling party’s Warsaw mayoral candidate, worked on a property restitution law in 2017. But his draft was frowned upon and condemned by the Israeli government and Jewish organizations, who saw it as draconic.

Yaki’s bill stated that a survivor who wishes to claim property has to be a Polish citizen today, and had to live in Poland when the property was nationalized by the Communist rule. This means most survivors, who left during or right after the Holocaust, are not eligible to claim properties.

In light of the criticism of the bill, Poland withdrew the legislation for further assessment, and it isn’t expected to be discussed until after elections—meaning 2020. Meanwhile, Holocaust survivors are dying, and it’s unlikely that their heirs would be able to sue for properties and restitution.

Gideon Taylor, chair of Operations and Treasure at WJRO, is angry: “I’m not pleased by the recent developments. I was expecting Warsaw to disclose all information about properties in a public manner that would allow property owners to file suits. We demand they set up a longer deadline and disclose all details about assets.”

Yoram’s wife, Lusha, can’t use the newly-discovered book to retrieve her family’s property. “To speak of property and assets is no shame,” she says. “At our age, we are left alone. We are the last survivors left. We want to die in better conditions than the ones we live in today. We need restitution for our suffering—no parents, no childhood. The property claims are claims for justice, since it’s a disgrace that 80 year olds in Israel and around the world live penniless. The property clams will help me financially. For me, justice is also revenge.”