Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

In a small cafe in Qirmizi, Azerbaijan, a few elderly mountain Jews chat over a strong tea with sugar cubes. They speak Juhuro, the forsaken tongue of Caucasus Jews. It’s a kind of Persian mixed with Hebrew.

and Twitter

One of them, an elderly man with a big white mustache and a black cap, proudly shows off his arm, decorated with a flower tattoo. “I had it done when I was 20 years old. So that when I’m old, I’ll remember my youthful days,” he said.

The cafe has a small shaded yard with two tables covered in oilcloth, and a pile of firewood next to them. It gets cold here in winters, on the foothills of the Greater Caucasus. An old Lada, essentially a tin can on wheels, is parked under a weeping willow tree. There are many Ladas on Azerbaijan’s roads, plodding alongside some extremely luxurious cars.

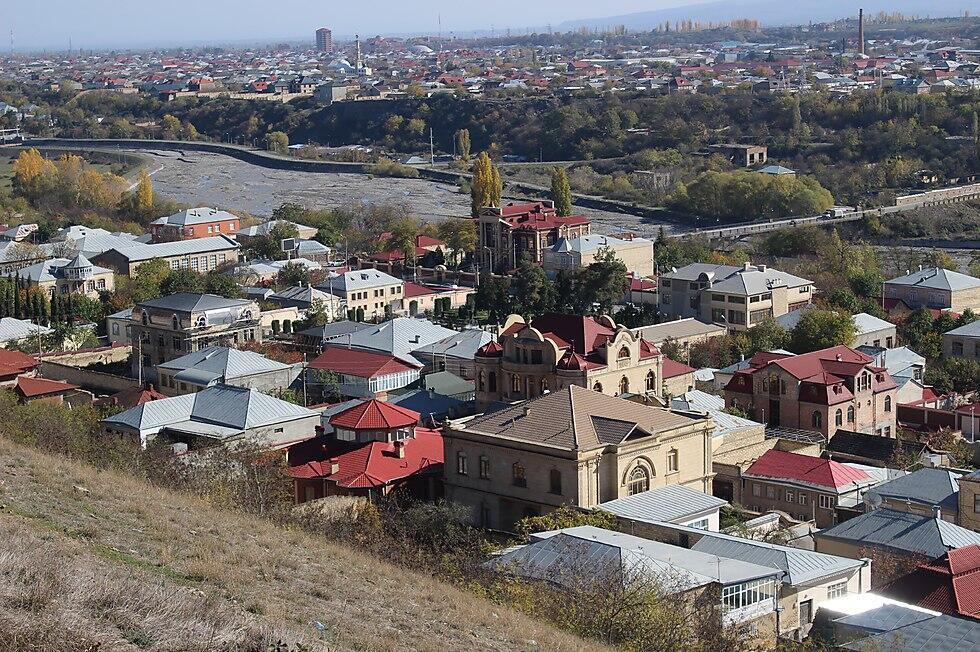

Qirmizi Qəsəbə, also known as Krasnaya Sloboda ("Red Village" in Russian), is one of only two communties outside Israel with an entirely Jewish population (the second being Kiryas Joel in New York State.) Some 3,000-4,000 people live here, but at noon the streets appear empty.

Some residents have businesses in Moscow and only come here for the holidays. The grand manse of Zerach Ilayev, a man whose fortune is estimated at $3 billion, stands empty in the center of town.

The air is full of longing—a longing for the children who have left, for the grandchildren who live in Israel or the US. A longing for the days when this place was called the Jerusalem of the Caucasus.

But Qirmizi still has a lively side to it, which we experienced in the cemetery, of all places. We visited with our wonderful guide Elchin Mammadov (Eli), who wished to visit his mother’s grave.

The first thing you notice in the cemetery is the faces—dozens of faces looking at you from all the black tombstones. The faces of the dead men, women and children.

Some tombstones are covered in white plastic. The custom here is to only unveil the tombstone a year after the parting, and until then it’s kept covered.

One tombstone has a stone bird figurine on it. “This means the deceased left no children behind him,” our guide explains.

We spot a small area with four tombstones together: mother Golda, father Ephraim and children Eliya and Hava. Eliya was seven and Hava was five when the whole family died in a plane crash in Russia 10 years ago. A marble plaque shows a family picture under the image of a Boeing 737.

Down the road are the older graves, from a century ago, some broken and others almost illegible. Hezi, the graveyard keeper asked us to translate some inscriptions from Hebrew. “Here lies the woman who was killed by brutal gentiles in Quba. Shunamit daughter of Nisan, in the year 5678 (1918).”

The Quba in question is Azerbaijan’s capital of carpet weaving and apple plantations, located across the River Kudyal from the capital Baku.The river is dry in early winter, but when the snows thaw up in the summits, it overflows.

Matchmaking in Azerbaijan

Three bridges separate Qirmizi and Quba. One of them, a bridge that’s closed to vehicles, is referred to as "‘the love bridge" — and functions as the city’s JDate. This is where the single Jewish men and women come to meet a match.

“Girls walk the bridge with their mothers,” Eli explains, “while the guys look on from the banks. If a guy sees a girl he likes, his parents will approach her parents and ask for her hand.”

Not exactly what you would find on the curriculum of a gender studies program, but in Azerbaijan, it works. Around the corner from the bridge is the city’s wedding venue — a pillared hall that houses weddings, bar mitzvahs and circumcisions. There’s a huge photo of the Western Wall inside.

“So what kind of presents do you bring?” we asked our guide. “Checks, of course,” he said. “A minimum of 100 Azeri manat”—the equivalent of NIS 220 or approximately $60.

Caucasus weddings are a good deal

A local kosher restaurant supplies everything you need for the big day. The feast menu includes juicy kebabs that can also be found everywhere from roadside stalls en route to Baku to the fancy restaurants once you get there; Dushpere, a soup with meat-stuffed dumplings; and Dolma—vine or cabbage leaves stuffed with meat.

Then there’s the pickles, of course—not only cucumbers, but also olives, peppers stuffed with cabbage, tomatoes and cherries. And add alcohol, and a band that plays Azar music with Persian instruments like kamāncha and Tar. All this for $22 per person—not a bad deal.

Azerbaijan pays its respect for the Jews

Azerbaijan is a Muslim Shiite country, with most Azaris living in nearby Iran and making up 25% of the population there. But people here love Israel, and not only because we buy their oil and sell them weapons (including Iron Dome systems, which are lined across the Azari border with Armenia.)

The local Jews are respected and treated with tolerance. In central Baku, Jews wearing kippas walk around undisturbed—not something you would see in Paris or other European cities nowadays.

A small sign informs us of the contribution of Azari Jews to their homeland: a plaque commemorating a young Jew, Albert Agrovich, who fought and died in the infamous war against Armenia in the 1990s over the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region.

By the tea house there’s a statue of a Soviet soldier, commemorating “the Great Patriotic War,” during which the Red Army stopped Hitler from conquering the oil-rich Caucasus and murdering its Jewish population.

A prayer book in Juhuri

During Soviet times, there were 11 synagogues in Qirmizi, but they weren’t in use — Communism was the only religion. And yet the mountain Jews continued to preserve their faith and customs in their homes—observing the Sabbath, fasting on Yom Kippur. Most of them didn’t even know why.

“If you asked a Jew why he observes Shabbat, the answer was ‘because my grandfather told me to,” says Eli.

Today there are only two synagogues left in in the town, but they are both active. The larger one was closed so we visit the smaller one. The beadle asks us to remove our shoes, and when we enter we understood why: the floor is adorned with colorful and magnificent Azari carpets (such a carpet can reach a cost of NIS 10,000 or $2,500).

Every day 25-30 people come to pray here, and during holidays it’s packed. There’s even a Siddur (Jewish prayer book) in Juhuru, the local dialect. Neither my wife nor I are religious, but here, standing in the last Jewish town in Azerbaijan, we pray.