Even for Or-Ner, who is considered an outsider in the Israeli art scene and whose creations have always been described as unusual, this was extreme. It was so extreme that in 2006, when he had an exhibition at a Tel Aviv gallery titled "My friend Hitler," the police showed up and ordered him to close up shop. "Well, in the end we worked it out and the exhibition went on," he says with a smile.

The police raid didn't stop Or-Ner. Nothing could prevent him from continuing to create to his heart's desire—a desire that hasn't always been fully understood.

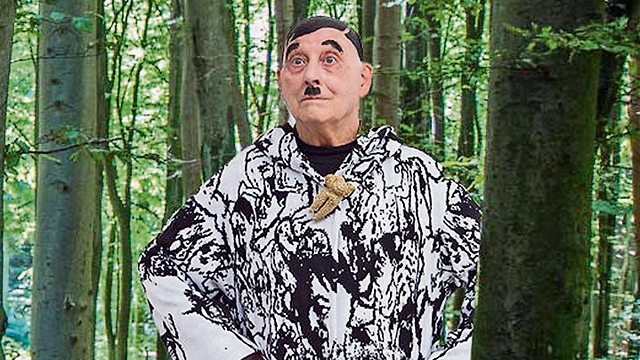

Shortly after that, he created the character of "Bud Ranrua" (an anagram of his name in Hebrew), which resembles a grotesque and ridiculous version of Hitler. To get into the role, the 92-year-old Or-Ner paints his bald head black and draws a small moustache under his nose, and in this getup he goes out into the world.

"I once walked around like this at the Tel Aviv Central Bus Station, but to my surprise there was no reaction," he says. "Sometimes I walk around like that at Kibbutz Hatzor, where I live. At first people didn't recognize me. Even my wife, who has since passed away, didn't recognize me the first time she saw me in costume."

Did you get reactions from people who were against this, who were outraged?

"There are no violent reactions. Normally people talk to me and ask me why I'm doing this thing, and what does it mean."

And why are you doing this thing? What does it mean?

"Even I don't really know how to explain it. It's a character that lives with me, and we get along mostly. When I'm in this character I feel good, 50 years younger."

This unusual relationship between Or-Ner and Hitler hit a new high last week when "Bud Ranrua" appeared for the first time at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, one of the central institutions of Israel's art scene, as part of the exhibition "Kibbutz Buchenwald" by Gil Yefman, who won the Rappaport Prize for young artists.

Yefman collaborated with Or-Ner on one of the works in the exhibition, both of them dressing up as their alter-egos—in Yefman's case, it's Penelope, a colorful and joyful African woman—and taking pictures with the Buchenwald concentration camp as the backdrop. In this manner, they are bringing Hitler back to the scene of the crime, but in a manner that can be seen as a bad joke.

It turns out the name of the exhibition, which could be seen as provocative in and of itself, refers to something that actually existed: Kibbutz Buchenwald, which was founded by Holocaust survivors near Ness Ziona in 1948, but after much opposition was renamed Netzer Sereni and exists to this very day. As part of the exhibition, Bud Ranrua and Penelope were photographed walking the kibbutz's paths.

The outsider

Despite being a very pleasant person, Or-Ner has never been easy to understand. We meet at his studio in Kibbutz Hatzor. Photos of him dressed like Hitler are on the walls, alongside countless sketches, paintings and statues he created. Even at his age, he still rides his bicycle here every morning."I have a hearing problem, sometimes you might have to repeat the question," Or-Ner says apologetically at the beginning of our conversation.

His voice is weak and shaky, but what's left of his French accent can still easily be detected. "We were French, I barely knew we were Jews," he says.

All of that changed in September 1939, when the young Or-Ner returned home to find his parents listening to the radio. To this day, 80 years later, he clearly remembers the strange sounds coming out of the radio, the likes of which he had not heard before. "It sounded like the barking of a wounded dog," he says.

Later he would learn these strange sounds were the voice of Adolf Hitler, who was making a speech after the Nazi occupation of Poland—the move that launched the Second World War and with it the Holocaust. "This voice remained within me for years. It really bothered me, physically. It was hard for me to speak," he says.

Hitler's terrible barking accompanied Or-Ner when he escaped Paris with his parents to a distant village, and when his mother and father were arrested and sent to an extermination camp, never to return. This devil wouldn't let go of him even as he survived the war alone on the street, when he returned to Paris and stayed at a shelter for orphans, when he made Aliyah to Israel, and when he joined Kibbutz Hatzor and became one of the unique figures in the Israeli art scene.

"But about 15 years ago, something happened," Or-Ner says. "Hitler's voice started coming out."

Hitler may be taboo to most of us, but to Or-Ner he has become a sort of a friend in recent years. It would not be an exaggeration to say that his almost obsessive occupation with Hitler brings a sort of comfort to the Holocaust survivor.

Either way, his work caught the eye of Gil Yefman, a young artist who started visiting Or-Ner's studio and struck up a friendship with him. "A year and a half ago, Gil sat right here, where you're sitting now, and asked me if I've ever heard of Kibbutz Buchenwald," Or-Ner says. "When I heard this, I looked at him wide-eyed. Kibbutz? Buchenwald? It didn't add up. This is where the entire process began."

The connection between the young Yefman and the older Or-Ner is now at the basis of the exhibition that opened last week at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, which deals with the memory of the Holocaust in a considerably unusual manner. For the first time, Or-Ner is being embraced by the Israeli art scene after decades of solely cold shoulders.

Or-Ner may indeed have been part of the most important Israeli art exhibitions of the 1970s, represented Israel in the 1972 Paris Biennale and the 1980 São Paulo Biennial, and even won the National Education Award in 1996, but he always preferred working away from the media's watchful eye and steered clear of the artistic cliques. Even though he is one of the most productive veteran artists in Israel, who influenced many artists and collaborated with dozens of creators, he has never gotten his own exhibition at a museum.

Now, Or-Ner is coming in through the back door to the very heart of the mainstream thanks to his collaboration with Yefman.

"It doesn't matter to me if I'm in or out. The most important thing is that I could do my things, things I love," he says. "Normally that means being here, in the studio, working and creating. Sometimes my things come out, other times I bury them; that happens too. What I mostly love is collaborations with other, young artists."