Comedians in the Middle East play an important role in combating all forms of extremism, a veteran Jordanian comedian has said, amid a widening controversy over streaming giant Netflix’s decision to yank an episode of Patriot Act with Hasan Minhaj in Saudi Arabia.

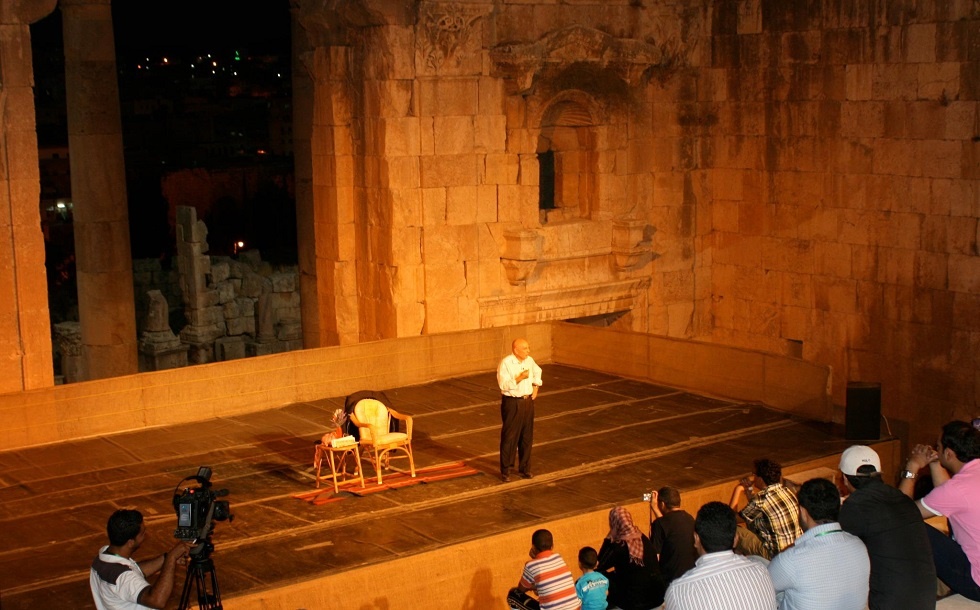

“The biggest enemy of extremism and fundamentalism is comedy,” Nabil Sawalha, who has been performed for nearly five decades in stage plays, films and television, said. “In Jordan, there are so many stand-up comedians now, as well as in Lebanon, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf countries.”

In response to a request by the Saudi Communications and Information Technology Commission, Netflix has removed an episode in Saudi Arabia in which comedian Hasan Minhaj ridicules attempts by the Saudi authorities to downplay crown prince Mohammed bin Salman’s role in the murder of U.S.-based journalist Jamal Khashoggi. The Saudi government charged that the segment, which remains available outside the kingdom, violated the country’s broad anti-cybercrime law, which forbids the “production, preparation, transmission or storage of material impinging on public order, religious values, public morals and privacy online.”

Sawalha—who has performed in Qatar, Dubai, Lebanon, Israel, the Palestinian Territories and the UK, among others—underlined that comedians in Jordan are mostly free to do as they please.

“In Jordan, we don’t have censorship and what you do is your responsibility,” he said, noting that the art form had recently taken off across the Middle East and had escaped restrictions, for the most part. However, due to unending conflicts and war, some comedians have been forced to change their routines.

“Politics in the Arab world has gotten very messy and so sometimes there is are no punch lines to laugh at,” Sawalha explained. “The degree of tolerance to comedy has gone down because of religious upheaval—in the face of IS and other violent groups—and this makes people a bit narrow-minded. So, most comedians deal with everyday issues. You don’t touch religion in any shape or form. But we used to put all the sheikhs on stage.”

Sawalha revealed that he generally avoids political issues like those connected to Syria or Iraq because of ongoing violence. He also stressed that the only instance in which he personally encountered limits on his material occurred when he was invited to perform on Jordanian state television. There, he said, producers requested that he refrain from mocking the government; he eventually decided against making an appearance.

“Humor is incredible now in the Arab world because of social media, which the authorities cannot control,” Sawalha said. “Political humor is doing what it was originally made to do: release the pressure felt against dictators, negative social issues and for Palestinian comedians—the occupation.”

Others believe the firestorm and attention being given to Netflix and Minhaj, who has an Indian-Muslim background, stems from a deeply ingrained system of discrimination against other Middle Eastern comedians.

“I don’t believe Indian Muslims experience the depth of the discrimination that Arab Muslims face in the news media. If Minhaj were a Palestinian or Christian, the media would not have cared if the show had been banned in Saudi Arabia or any Arab country,” Ray Hanania, a Christian-Palestinian comedian who currently resides in the United States, said. “I think American society overall discriminates against real Middle Eastern comedians", he said.

“Palestinian comedians like me are excluded and marginalized,” he added. “In America, the reality of racism and discrimination of Arabs and Muslims is measured not by lynching or violence but by social ostracism.”

Hanania, an award-winning political and comedy columnist launched an Israeli-Palestinian Comedy Tour which brought together Israeli and Palestinian comedians following the September 11 attacks.

“As a Christian-Palestinian comedian, I experience the worst discrimination from mainstream news and entertainment media, and from political extremists who dominate the dialogue in America,” he said. “I am ignored by non-Arab Muslims because I am irrelevant to them. It’s very important for comedians to express themselves but they have to have the opportunity to do so.”

In Israel, stand-up comedians praised the willingness of Israeli audiences to hear jokes that are often deemed less acceptable to Western ears. Comedian Mike Kroll, who is originally from Texas, has been performing for the past 12 years and said his career only took off after he moved to Israel.

“I’m a firm believer that you shouldn’t apologize for your comedy if you’re not hurting anyone,” Kroll, who often performs dressed as a drag queen, said, adding that only once an audience member confronted him over his material.

“I’ve never encountered an audience or venue that would limit what I say or what I want to get across,” he continued. “In terms of content, it’s very free in Israel. People in the West are picking apart comedians, but thankfully in Israel, we’re so small and there are so many bigger issues to deal with, that comedy can grow in a positive way.

Similarly, Israeli-American comedian, educator and writer Benji Lovitt—who has been performing for the past two decades—says he does not feel hampered by so-called political correctness or censorship in Israel, but argued the same could not be said of the West.

“What happens in America or Europe is that people are getting offended and calling for someone’s head every other day—and sometimes that's ok, but sometimes people miss the joke or are triggered by something,” Lovitt said. “I think that when we lose the ability to look at someone’s intent and actually think critically, that’s when there’s a problem.”

As an example, Lovitt pointed to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, a thorny issue he admittedly avoids in the U.S. “When people hear jokes about sensitive topics often they don’t get it, they automatically think: ‘Uh oh, am I allowed to laugh at this?’ That’s what annoys me: when people lose the ability to really get what’s being made fun of. Comedy has always been about pushing the envelope and making people think. But if audiences are no longer perceptive, that’s going to kill comedy," he said.

Article written by Maya Margit

Reprinted with permission from The Media Line