The phone is ringing on and on, but there's no answer at the Chief Rabbinate's Jerusalem district office. There's no answer in the South and Central district offices either. In Haifa, we get a surprise: There is an answering machine asking us to leave a message. We left one, but no one called us back. This is what the Jewish conversion system in the State of Israel looks like: There is no one to talk to.

As the state fails to offer an appropriate solution to those seeking to convert to Judaism, different alternatives are emerging in an effort to help the 400,000 Israelis who lives as Jews in Israel but are not considered Jews according to Halacha (Jewish law).

Within the discussion on conversions lies the particularly acute issue of the conversion of children under 13. There are tens of thousands of children living in Israel who were born here to parents who made Aliyah under the Israeli Law of Return, even though they are not considered Jews by Halacha. There are also hundreds of children who were adopted abroad, and close to a thousand children who were born abroad through surrogacy.

While the Chief Rabbinate has only converted a few dozens of minors over the past three years, alternative conversions have already been performed for hundreds of children.

Sigal and Erez, who live on a moshav in the Sharon region, had a daughter and wanted to extend the family. When their first-born was 12, the couple chose to have their next child through surrogacy. A young woman from Kiev carried their baby, which was conceived from Sigal's egg and Erez's sperm. When they returned home with baby Gilad, the couple learned their son is listed in the the civil registration as having no religion.

"I'm Jewish, my husband is Jewish, we grew up here, we served in the army. This bothered me. I'm not religious, but I am Jewish. I celebrate Hanukkah and not (the Russian New Year) Novy God," Sigal says. "We tried to contact the Chief Rabbinate; it's very hard to get hold of them. They don't answer emails or phone calls. My husband spent hours trying to reach them."

Having a child who was not recognized as a Jew because he was born through surrogacy meant that the family had to have their son convert into the faith, and that meant circumcision.

"We realized we had to do the brit milah (Jewish ritual circumcision) with a mohel who does conversions, very few of which are recognized in Israel. We found a lovely mohel who also does conversions, and he performed the brit milah. It was moving. We named our son Gilad," she says.

"We received the okay from the mohel and contacted the Chief Rabbinate again to start the process of conversion. Finally, we had a meeting scheduled. We didn't hide the fact we were secular; it's not a crime, it's a free country," Sigal says.

But at the meeting, it was made clear to the couple that unless they adopted fully a religious lifestyle, their son would not be able to convert. "When they demanded that not just Gilad, but our older daughter must also attend religious education institutions, I realized a red line had been crossed. It drove me crazy that they were unwilling to show leniency in any way, even though this baby was created from my egg, and no one questions the fact I'm Jewish," Sigal says.

There is a Halachic dispute over who is considered the biological mother of a baby—the egg donor or the surrogate. One view determines that the surrogate is the mother, Halachically speaking, and therefore even a fetus that was conceived from the egg of a Jewish woman, but grew in the womb of a non-Jewish woman, is not Jewish. The Chief Rabbinate has chosen to take this stringent position and demands the baby undergoes conversion even in such a case.

"We came out of every meeting at the Chief Rabbinate frustrated and in tears," Sigal says. "Because my husband's last name is Katz—meaning Kohen Tzedek (righteous priest)—they wouldn't allow this to be Gilad's last name as well. This is when my husband lost his cool. He almost flipped over the table, but he held back. We went through so much suffering, which was very unpleasant. We realized they don't care if Gilad remains non-Jewish."

Sigal and Eerz looked for another solution. After searching online, they found Giyur K’Halacha, an Orthodox non-governmental conversion court network. "They warmly embraced us. At the first meeting, I burst out crying telling them everything we've been through. In the second meeting, we did the conversion," Sigal says. "At the head of the court was Rabbi Stav, who was sensitive and accepting. Erez went with Gilad to a mikveh, which was well-kept and charming. We got a conversion certificate from them."

However, Giyur K’Halacha's conversion is not recognized by the Chief Rabbinate, which means Gilad won't be able to legally marry in the State of Israel.

Do-over with the second generation

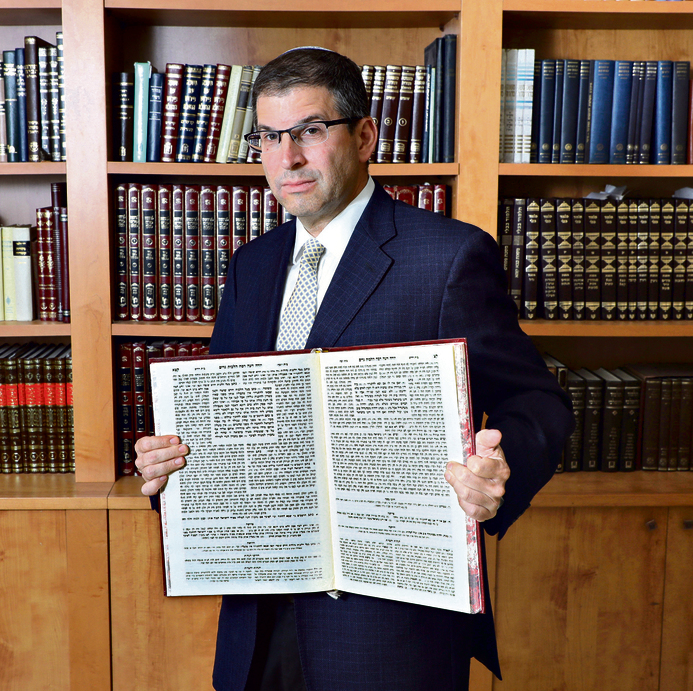

At the head of the Giyur K’Halacha network is Rabbi Prof. Nachum Rabinovitch, the head of the Ma'ale Adumim national-religious Hesder yeshiva. His partners include Rabbi Shlomo Riskin, Rabbi Re’em HaCohen, Rabbi David Stav and some 70 additional rabbis from the more liberal branches of the religious-Zionist community. The establishment of the organization some three years ago was seen as rebellion against the Chief Rabbinate and faced backlash from many movements within the religious-Zionist sector, mostly from the Chardal movement (national ultra-Orthodox).

"There are several Halachic views on the conversion of minors. Giyur K’Halacha is based on the rulings of Rabbi Moshe Feinstein (one of the most prominent ultra-Orthodox Halachic sages of the 20th century), who said the burden of mitzvahs should not be put on a minor under the age of Bar Mitzvah," says Rabbi Dr. Shaul Farber, one of the founders of the organization.

"There are other, more stringent positions that require the parents of the minor to uphold the mitzvahs, because anyone who allows the conversion of a child without ensuring he could live a religious life is setting him up to fail. But these are the stringent positions that do not represent the main Halachic movement that supports Rabbi Feinstein's ruling. Unfortunately, the official conversion authority in the State of Israel today chose the most stringent position for minors," says Rabbi Farber.

"A year and a half ago, the special committee for the conversion of minors in the official court in Jerusalem was closed, and since then the number of conversions of minors has been dropping," Rabbi Farber says. "Instead of making the process easier, they're only making it more stringent and demanding the parents fully uphold mitzvahs and for the child to only attend religious or Haredi educational institutions. We believe it's possible to solve—in a worthy and dignified Halahic manner—all the acute problems of conversions by converting the next generation, the minors. We missed the first generation, we now have the opportunity for a do-over with the second generation."

"This issue needs to be at the heart of the public discussion, certainly now ahead of the elections," he says. "Because of political considerations, and not Halachic ones, we will find ourselves in another generation facing a grave crisis of mixed marriages. It's a ticking time bomb. Our Halachic solution is the mass conversion of minors; the conversion of adults is a lot more complex. On this matter we agree with the Rabbinate, that when it comes to adults the conversion must include the acceptance of the full burden of mitzvahs. This is what separates us from the Reform Jews. But when it comes to children, there's no need for that."

What are your conditions for converting minors?

"Our basic condition is that the family doesn't later raise the child in a different religion, and that both parents—either biological or adoptive—want the conversion. Beyond that, it's important for the child to have a connection to the traditional Jewish world. Every child in the state's education system learns about the holidays and has a connection to the Jewish identity. We also do the conversion in cases the mother doesn't convert herself, on the condition she doesn't raise the child as Christian and that the Jewish holidays are celebrated at home. Furthermore, we only convert children who are Israeli citizens; we don't do conversions for children of foreign migrants or tourists.

"The conversion of minors that we do also includes an introductory meeting with the family to choose the path most suitable for them, after we present them with all of the possibilities. Some parents choose the Chief Rabbinate's official conversion track, despite the difficulties and stringent demands it entails. We also try to help them via the ITIM Institute, which accompanies the conversion process and increases the chances of a successful conversion through the Chief Rabbinate by 60 percent. If they choose to do the conversion through us, most of the time we do the conversion on the second meeting. We have a short course of four meetings for parents who want their children to undergo conversion. This course is optional, it doesn't constitute a condition for the conversion, and it does not require accepting the burden of mitzvahs, because Halachically speaking there is no requirement for a minor to fully take on the burden of mitzvahs. We recommend (the parents) to stay connected to the community and the synagogue."

Last September, the district court ordered the Interior Ministry to recognize the Jewish status of a woman who converted through Giyur K’Halacha. This unprecedented ruling was the first time a court in Israel recognized these alternative conversions and compared them to the status Reform and Conservative conversions hold in the State of Israel. Despite this, Giyur K’Halacha's conversions are still not recognized by the Chief Rabbinate.

"At this stage, (Giyur K’Halacha conversions) are not recognized," Farber says. "But we're in constant dialogue with the Halachic institution, and we hope and prepare for the day our conversions are recognized. We of course make it very clear to the people we perform conversions for that this still hasn't happened and might not happen. Everything is open and transparent with us, unlike the Chief Rabbinate. We explain to people they won't be able to legally marry in the State of Israel; they will have to marry in a civil ceremony outside Israel, and then they can do the religious ceremony in Israel. There are a lot of Orthodox rabbis who will marry them privately in Israel, in accordance with the laws of Moses and Israel."

Would you agree to your son marrying a woman who as a minor underwent Giyur K’Halacha conversion?

"Of course. It's a Halachic conversion to all intents and purposes."

How many children have you converted so far?

"More than 500 children over the past three years, and the numbers are only rising. People want an Orthodox conversion, but they are not willing to lie for it. The Chief Rabbinate's conversion forces people who are not religious to lie."

"This feeling is terrible. I will never forgive them for making liars out of us," says Na'ama (not her real name), who managed to have her daughter, who was born two years ago from an egg donation through surrogacy, undergo conversion with the Chief Rabbinate.

"We're secular, but just like it was important to our parents that we get married through the Chief Rabbinate, it was important to us that our daughter would be able to marry through the Chief Rabbinate. In this regard, Giyur K’Halacha can't help us. We went to the synagogue for a year, dressed differently, signed documents saying we'd send her to religious educational institutions—we did everything. There are wonderful rabbis in the community who were with us throughout, and we really feel bad (about deceiving them). For now, we were issued a conditional conversion certificate after my husband wept in front of the (Rabbinate) court. Meanwhile, he's still going to the synagogue on Shabbat because he feels bad, but we are secular, and we will remain so."

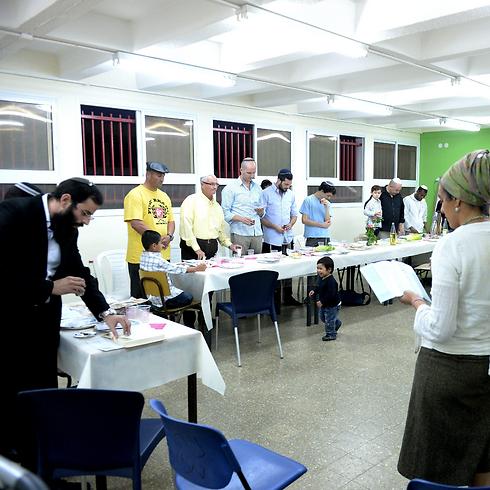

Wanted: Zera Yisrael

Rabbi David Ben-Nissan, who has been dealing with conversions for years through the state conversion institute Ami, helps parents of children born through surrogacy who wish to have their children undergo conversion through the Chief Rabbinate. Recently, Rabbi Ben-Nissan opened a private course for eight couples whose children are candidates for conversion. The first course took place in Herzliya over a period of six months, with one meeting a week, at a cost of NIS 2,000 per couple. The children of two of the couples who did the course have already undergone conversion through the Chief Rabbinate, and others are in the midst of the process. Another course is about to begin.

Another alternative is the Reform conversion system, which does conversions for some 220 people every year, including many minors. "We really embraced this field. There are a lot of children who were born through surrogacy. A lot of couples turn to us, but it's mostly same-sex couples who can't find a solution even among the most liberal of Orthodox. I meet with each family personally and accompany them (throughout the process)," says Rabbi Galia Sadan, who was recently appointed the director of the conversion court of the Reform Movement in Israel.

The popularity of Reform conversion in Israel began to grow after the High Court of Justice ordered the State of Israel in 2012 to recognize the conversions done by the Reform and the Conservative movements.

"The phones didn't stop ringing, people realized there was a conversion option that was not Orthodox, without anyone expecting them to become religious," Sadan says.

At the time, the Reform Movement launched a campaign under the slogan of "There is more than one way to become a Jew," which was plastered on buses across Israel. "I saw there was a demand. I had zero experience in conversion at the time, I was a student rabbi in the Rishon LeZion community. I spoke to the heads of our court, people who dealt with conversions in the past, to get the syllabus of the prep course. I opened a conversion class in Rishon LeZion with the help of more veteran rabbis and instructors," she says.

Later, Sadan opened a conversion class in Beit Daniel, the main community for Progressive Judaism in Tel Aviv, with the help of its founder Rabbi Meir Azari. The class is now offered in three languages: Hebrew, English and Russian. The curriculum, which was written by Sadan, takes a year to complete, and at the end of it the new converts arrive at a conversion court, where they immerse in the mikveh (Jewish ritual bath) as part of their conversion ceremony. Men are also required to undergo ritual circumcision.

"The Reform Movement is not a Halachic movement," Sadan says. "Conversion is the most Halachic institution within the Reform Movement. As for the mikveh immersion and the circumcision—we remain faithful to the 2,000-year-old tradition. The disagreement is over what it means to take on the burden of mitzvahs. Our conversion doesn't require one to accept the burden of mitzvahs, but it's important to us that people know the traditional Jewish law before converting. When a man joins a certain tradition, he needs to have a basis. You can't make choices within the tradition without knowing it at all. In the end, the people who undergo our courses know a lot more than any average Israeli.

"We have a shorter course for people who belong to Zera Yisrael (people who are blood descendants of Jews who, for one reason or another, are not legally Jewish according to religious criteria). Mostly these are people who grew up in Israeli educational institutions and already know the traditions. When it comes to the conversion of adopted minors, or minors born through surrogacy, or minors of Zera Yisrael whose father is Jewish but their mother isn't—the process doesn't include teaching the traditions, but a meeting about family life and the parents' commitment to raise their child as Jewish."

The desire to ensure the continuation of Jewish life led Ido (not his real name), a 50-year-old unmarried man, to decide to bring a child into the world. "I'm a special ed teacher. I went to Poland with a delegation of teachers shortly after my father, who was a Holocaust survivor, passed away. At Auschwitz, I decided I needed to add another branch to our family tree. I went back to Israel and began the surrogacy process. Today I raise Evyatar on my own. I'm not a religious man, even though I teach at a religious institution and therefore know all the traditions. My son underwent conversion through an Orthodox rabbi, but when I wanted to register him with the Chief Rabbinate, I was told that rabbi's conversions, which had previously been recognized, were no longer accepted. I went through a nightmare. Nothing I did helped. They demanded I bring documents to prove I was Jewish. When I turned to my mother and asked for proof that she was Jewish, she was deeply offended. She didn't sleep for several nights. They were asking her, a Holocaust survivor who is the descendent of a family of rabbis, to prove that she was Jewish. I gave up and I turned to Reform conversion. I was treated very respectfully. They even said there was no need for Evyatar to visit the mikveh again because they trusted the immersion he went through with the Orthodox court. Evyatar is growing up as a Jew, he is registered in the civil registration as a Jew, he went through both an Orthodox and a Reform conversion, but absurdly when he wants to marry, the Chief Rabbinate won't recognize him as Jewish."

Criticism of the Chief Rabbinate

"Anyone who talks to Israelis who have tried to undergo conversion through the Chief Rabbinate immediately hear of the drawn-out proceedings, the court's condescending attitude, and the attempt to push them into ultra-Orthodoxy before they even convert," says Gilad Kariv, the executive director of the Reform Movement in Israel.

"We don't intend to abandon tens of thousands of Israeli families to this hostile and belligerent institution. In the coming years, we intend to dramatically expand our conversion activities across the country, and go from the conversion of hundreds every year to thousands. This is our duty toward the tens of thousands of Israeli families who made Aliyah under the Law of Return, and all the families who adopt children. Any government that tries to stop this Jewish and Zionist mission through legislation will be met with fierce and uncompromising opposition in Israel and in the Diaspora. The Haredi parties have been trying to promote conversion legislation since the days of (David) Ben-Gurion—and fail every time. Along with most of the Israeli public and world Jewry, we'll make sure they don't succeed in the future either."

"The existing situation doesn't bother me," says Rabbi Sadan. "The state recognizes our conversions for the purposes of civil registration. The situation may overload the courts, because the court needs to approve each conversion certificate we issue—as the state won't put its seal of approval on our certificates itself. It also costs our converts more: they have to pay a NIS 1,200 fee to the court and NIS 300 more to our lawyer who deals with this."

Doesn't it bother you that people who undergo your conversion won't be able to marry Orthodox Jews?

"They could be married by us. There needs to be civil marriage in this country, allowing each person to choose the religious ceremony that works for them."

Do you think there is a chance the different Jewish streams could cooperate on the conversion of minors, to avoid having separate marriage lists for each?

"We have a disagreement with the liberal Orthodox over the conversion of surrogacy children born to gay parents, having women judges in the rabbinical court and the presence of men when women immerse in the mikveh. We are very strict about not having a female attendant when men visit the mikveh and not having male presence when women visit in the mikveh. However, I'm willing to have a round table discussion to think together about a shared mechanism for the conversion of minors."

Rabbi Farber, meanwhile, says there are those on the Orthodox side who are also searching for a more liberal way. "Regarding the conversion of surrogacy children of gay couples, we're holding internal discussions in Giyur K’Halacha about the issue. We would be happy to provide an appropriate solution to this public, but there are different voices, and there are rabbis who say the court can't recognize a couple living together against Halacha laws.

"Regarding the integration of women in the court, this is an issue that cannot be ignored. It's possible we could come up with solutions, such as expanding the court's panel to include more than three rabbinical judges and add women. As a private individual, I believe the Halacha is supposed to provide an answer to everyone and should know how to operate in this new reality that has been created in the State of Israel and in the Jewish world. The Halacha solution should be one that is respectful toward everyone and provides a solution for everyone. We shouldn't rule out the rights of Reform Jews, or tell them that everything they're doing is worthless. To me, it's better for a Jew to attend a Reform synagogue on Shabbat than go to the beach. I'm a man of Halacha, but does that mean that as part of my Halacha I need to step over anyone who doesn't believe in that Halacha? No. I can respect him."

Do you think the Chief Rabbinate should maintain its monopoly, or would it be better if conversions and marriages were privatized?

"There are differing opinions about that matter among the 70 rabbis who support Giyur K’Halacha. There are rabbis who prefer a strong Chief Rabbinate, but hope it acts in a way that brings people together and without unnecessarily stringent demands, and there are rabbis who say it's better to privatize everything. To me, this question isn't binary—either a Chief Rabbinate or privatization. The Jewish world doesn't want chaos, but it also doesn't want such a centralized and strict Chief Rabbinate. There are other, more pluralistic models that maintain order and stability but at the same time still respect each person's choices on how to live a Jewish life."

The Chief Rabbinate's conversions authority offered the following response: "The treatment of people undergoing conversion is respectable throughout the entire process. Minors specifically are handled with great sensitivity, as we keep in mind the challenges entailed in the conversion process. The demands concerning the lifestyle of the family during the conversion process are determined by the Chief Rabbinate to ensure a uniform and Halachically valid conversion."

The head of the Chief Rabbinate's conversions department, Rabbi Moshe Veller, added that, "the conversion court's approach is based on the majority opinion in Halacha in an effort to maintain unity among the people and not divide them."