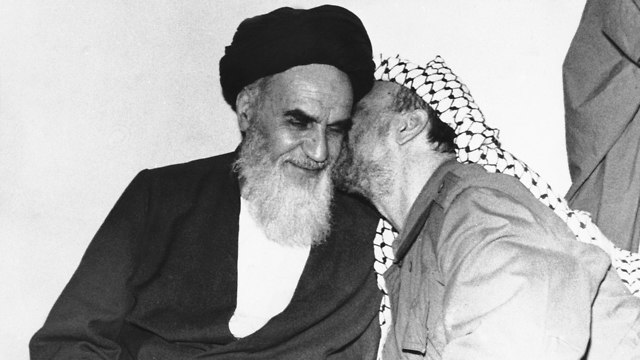

Ayatollah Khomeini

Photo: Getty Images

They were born after their parents' protests brought down the shah of Iran in 1979, when enthusiasm gave way to the hard years of US-led isolation and a bloody, eight-year war with Iraq.

Iran's "revolution babies" are a major force in the country today, in the wake of the overthrow of Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and the creation of the Islamic Republic, now marking its 40th anniversary.

More than half of Iran's 80 million people are under 35, and all of them deal with the legacy of the uprising, especially as the country struggles anew under re-imposed US economic sanctions after President Donald Trump pulled Washington out of Tehran's nuclear agreement with world powers last year.

For many, the objectives of the revolution are still elusive.

"We had some goals and still believe those goals were right," said Farzad Farahani, a 22-year-old university student. "We had demands and still think those demands were fair, but the revolution failed to fully realize our demands."

Besides installing the Shiite theocracy that governs today, the Islamic Revolution touted independence from both the West and the East. It also came with a host of plans pushed by the leftists who joined forces with Iran's clergy, including economic development, education and social justice. Its leaders promised the people a share of Iran's lucrative oil sales.

Today, nearly every Iranian can read, compared with only 47 percent in 1976, according to government statistics at the time. College enrollment is high, as evidenced by the crowds of young people on the streets near Tehran University.

But at least one in four can't find work, according to the International Monetary Fund, amid Iran's 11 percent unemployment overall. Those who do find jobs often take positions below their means, such as those with doctorates driving taxi cabs.

Mania Filum, a 27-year-old student, said the revolution did produce more educated Iranians, but now she and her friends are determined to leave if there's an opportunity abroad.

"Everybody plans to win funds for Ph.D.s and leave Iran," Filum said. "Those who are staying, it's because they have rich daddies, or dads that own factories or good jobs. They can have a job and have a stable situation."

Iran has a large youth population, in part because family planning clinics were dismantled after the revolution. The government aimed for an "army of 20 million" of loyalists to confront "global arrogance" and lead the Muslim world.

Many also grew up after a bloody war in the 1980s that Iraq launched against Iran and saw 1 million killed.

"The economic situation is very bad. My father went to the war and was wounded in action, he was ready to sacrifice his life, and he loved Imam (Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini)," said Kimia Zakeri, a 20-year-old student.

"Even now, when we talk, he doesn't want to accept the reality and the bad situation," Zakeri said. "My parents are very unhappy. They think that the economic situation should have been much better. People's beliefs are a bit less firm than before."

Zakeri added: "You can't have any fun or buy anything. You just have to make ends meet so that you can breathe and survive."

The younger generation has known times of incredible political pressure — and a brief thaw.

Western sanctions have been a fact of life for decades in the wake of the storming of the US Embassy in Tehran in 1979 and the 444-day hostage crisis that saw Iranians chanting "Death to America!"

There was a sense of optimism in 2015, when Iran reached the nuclear deal in which it limited its enrichment of uranium in exchange for the lifting of sanctions. But that hope has now faded under Trump, who withdrew from the agreement over Iran's growing role in the region and its ballistic missile program.

Shayan Momeni, a 27-year-old dentistry student, blames Iran's current problems on the United States.

"It mostly doesn't have anything to do with the revolution. It's mostly America's muscle-flexing," he said. "America likes to dominate the Middle East, but it can't achieve that. Now it's struggling to bring us to our knees, but it hasn't succeeded."

Filum, the other student, disagreed.

"Japan could have cut its ties with America forever after Hiroshima and could have kept saying, 'Death to America' until now, but it kept its ties, enjoyed the benefits, and this greatly helped its progress," she said. "But Iran is not like that. It still insists that America is bad, it's our enemy. Britain is bad, it's our enemy."

She asked: "This is independence at what price? At the cost of our lives getting worse?"

Those views are shared by many who grew up with growing access to the internet and satellite TV channels that offer views far different than Iran's state-run broadcasters.

But they also watched as the 2011 Arab Spring protests sputtered out into wars and repression, a warning for them amid increased US pressure targeting Iran's government. They also remember the chaos and crackdown that followed Iran's disputed 2009 presidential election.

Farahani said he believes that, in general, revolutions are not a good thing.

"I think reforms are better than revolution and making radical changes that destroy good things too," he said.

Mohammad Ahadi, a 25-year-old cook, is proud of the progress Iran has made.

"Before this 40-year period, people had no say," Ahadi noted outside a Tehran mosque where he had just prayed. "But today, when we look at everything after 40 years, our missile and nuclear technology and our achievements in the Middle East and around the world are talked about everywhere. It's a great feeling, and we feel powerful."

Even with the economic sanctions, he sees a defiance that brings independence, and that "is well worth it."

"Yes, America is ahead of us, because it started to work 300 years ago, but our revolution started only 40 years ago," Ahadi added. "If the revolution hadn't happened, we would have now been in a position like Saudi Arabia. ... Our entire lives -- even our breathing -- would depend on America."