They grew up in Syria, Afghanistan and Somalia and can place Israel on a map, but many young refugees in Sweden have never heard of the Holocaust.

Their first contact with Jewish history in Europe is often in the classroom and sometimes from the teachers themselves.

"One of my teachers was harassed by other students. He's Jewish and they made fun of him all the time," says Nergis Resne, a 19-year-old born in Sweden to Turkish-Macedonian parents.

She has since joined the group Young People Against Anti-Semitism and Xenophobia founded by Siavosh Derakthi in Malmö, Sweden's third-biggest city where one in three inhabitants was born abroad.

Organizations and a foundation started by Stieg Larsson, the late author of the best-selling Millennium crime trilogy, are taking on the challenge of helping students and teachers fight against anti-Semitism.

Despite online threats against him, Derakthi, 27, organizes seminars in schools, group talks and study visits to former concentration camps to raise young people's awareness of the horrors of the mass killing of Jews during World War Two and the need for peaceful co-existence.

"Some of them come from dictatorships, from warzones brimming with anti-Semitic, homophobic and misogynistic beliefs," explains Derakthi, originally from Iran, who in 2013 won the first Raoul Wallenberg Prize in honor of the Swedish diplomat who save thousands of Jews in the war.

Educators say their job is made more difficult by the vast amount of prejudice, fake news and conspiracy theories circulating on social networks.

"The most popular is without a doubt YouTube, where the radical far-right propaganda and the propaganda from radical Islam occasionally overlap," says Jonathan Leman, a researcher at the Larsson-founded Expo foundation.

Expo put together a booklet after 90 of the 100 teachers it surveyed in 2016 said their students believed conspiracy theories including that the Holocaust either never happened or did not happen in the way it's told in history books.

The imam and the rabbi

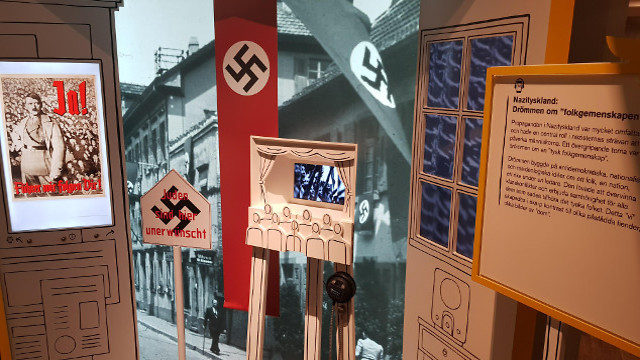

A stone's throw from Expo, in Stockholm's Old Town, Ingrid Lomfors welcomes thousands of students each year to the Living History Forum museum. Here the aim is to foster understanding by appealing to people's compassion and touching their hearts, rather than giving lessons in morality.

"Last year I had a wonderful exchange with three young Muslim girls about Anne Frank," the Jewish girl in Amsterdam who wrote a diary before she died in a concentration camp, says Lomfors.

"They knew nothing about Anne Frank. They walked through the exhibit, and then at the end two of them told me they identified with her, because of the isolation, the constant threats, the persecution, not knowing if they'd be alive the next day."

In Malmö, Imam Salahuddin Bakarat and Rabbi Moshe-David HaCohen have together founded the Amanah project aimed at building bridges between their two communities through festivals, workshops and lectures.

The challenge is rendered even more difficult by urban segregation, with large numbers of immigrant youths concentrated in the same neighborhoods and schools.

Swedes see anti-Semitism growing

According to the most recent report by the Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention in 2016, three percent of crimes of religious, ethnic, political or sexual nature had an anti-Semitic character, in a country of 10 million people that is home to 15,000 to 20,000 Jews.

In one such case, young migrants from Syria and the Palestinian territories were convicted for throwing Molotov cocktails at a synagogue in Gothenburg in December 2017. No one was injured in the attack.

In 2016, anti-Muslim crimes were more than twice as common as anti-Semitic ones, at seven percent. Mosques and migrant housing centers were the targets of numerous attacks.

Police have not seen any significant rise in the number of anti-Semitic crimes reported since 2014, even though Sweden has taken in 400,000 migrants since then, more than any other European country per capita. Sweden does not include ethnicity in its crime statistics.

Last year 35 police reports of anti-Semitic crimes were filed in Malmö, a number seen as stable but in all likelihood below the actual number, suggests Malmö police official Zandra Brodd.

Meanwhile three out of four Swedes believe anti-Semitism has grown in the past five years – the highest proportion in the European Union – according to a Eurobarometer study published by the European Commission in December.

"Many Jews choose to keep a low profile in public. They may for example hide a Star of David pendant inside their shirt or take off their kippah as soon as they leave the synagogue," says a spokesman for Malmö's Jewish community, Fredrik Sieradzki.

In January, Swedish Prime Minister Stefan Löfven pledged to allocate more funding so more youths can visit Holocaust memorial sites in Europe, and Sweden will host an international genocide conference in 2020.