Then Sadat said: ‘No one believed that I truly sought peace’

When the Egyptian president announced that he was ready to go to Jerusalem to make peace, few believed he was serious. As a young journalist accompanying the Israeli delegation in Cairo, Smadar Perry earned an exclusive interview with Sadat and also got to enjoy the other pleasures Cairo offered.

Only by coincidence did I recognize Sayed Marey, the speaker of the Egyptian parliament, from photos in Egyptian newspapers. He had just exited his vehicle and entered the Peace Gallery in Cairo via the back door. I knew this would be a unique opportunity for me, so I broke away from the other Israeli journalists without attracting too much attention.

It was the first ever visit by Israelis to Egypt, December of 1977, and we were sated by the treats of the luxurious Mena House Hotel at the foot of the Pyramids, so we decided to run off to the big city.

The Egyptians actually thought that they could keep us cooped up in the hotel, with organized daily outings to the three pyramids and the Sphinx. We left, accompanied by a security detail, in the morning and breathlessly climbed the stones of the pyramids, visited the Sphinx multiple times and everything was refreshingly novel and full of promise — until we became accustomed and fed up.

It did not occur to Sayed Marey, whose son was married to President Sadat’s daughter Nuha, that I was an Israeli. I cautiously drew near and speaking in English expressed my desire to interview the speaker of the parliament.

The security guards immediately cleared the way for me and I approached Marey and identified myself as Israeli. His face lit up with a huge smile. “Let’s speak after I deliver the opening remarks for the gallery,” he said and gestured toward a pair of seats in the corner of the hall.

Then he revealed to me, for the first time, the meeting between Moshe Dayan and Hassan Tuhami, Sadat’s adviser, in Morocco. “If not for that meeting,” Marey said, “President Sadat would not have travelled to Jerusalem and you, Israelis, would not be freely roaming in Cairo.”

We spoke of Sadat’s expectations’ of these trips, that were supposed to result in a peace deal between Israel and Egypt and Marey revealed to me how Sadat had visited Syria just before his famed visit to Israel and nearly paid with his life.

“Sadat wished for (Syrian President Hafez) Assad to join him on his peace trip,” he said, adding: “But Assad was furious and planned to assassinate the Egyptian leader while he was in Syria.”

I requested of Marey to arrange an interview with Sadat for me. He expressed a willingness to do so, gave me his number and asked that I call him in 10 days or so.

Birthday interview

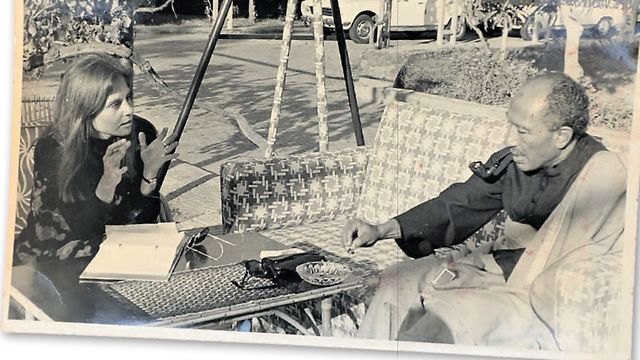

In retrospect, it is still hard to grasp the meeting with Sadat in all its aspects. I arrived on his 60th birthday and he chose to celebrate it, as he always did, at his hometown of Mit Abu El Kom in the Monufia district in the Nile delta. I entered the modest house, surrounded by a large garden, accompanied by Anis Mansur, the editor of the October Magazine and a close confidant of the Egyptian president.

Sadat was in the midst of an interview with Himat Mustafa of Egyptian television and someone motioned to us to wait. We were served mango juice and Mansur implored that I do not address Sadat with Chutzpah (disrespect) “as you Israelis are accustomed to speaking with your leaders.”

It was Sadat’s first interview to the Israeli media. Each word was fresh; each sentence intended to excite the reader. When the president’s aide motioned for me to approach, I clutched my recording equipment and then Sadat drew me into a completely unexpected trap.

He sat down on a swinging bench and invited me to sit to his right on the bench. At some point, Sadat began to speak enthusiastically about the peace initiative and of the benefits peace would bring. I managed to see how Mansur was relaxing in his armchair and grinning to himself. No doubt he saw how I had trouble keeping up with all the swinging. I almost fainted from excitement, or vomit my soul because of the motion. Fortunately, my recorder did its job and captured the event.

Sadat chose to begin with tales about his previous career as a senior journalist and editor of the daily al-Gomhuria (The Republic), one of Egypt’s three official, major periodicals. “I accepted the position halfheartedly and tried to make it into a true newspaper, with special stories and exclusive content,” he told. “But the journalists were lazy. They preferred to print content that was fed to them and did not try to seek out genuinely interesting material.”

Then Sadat began to tell me how the Egyptian parliament reacted to the peace initiative. I could not restrain myself and I revealed to him how the initiative was hardly accepted by Israelis at first, even in the media.

“I delivered a celebratory speech from the dais at the parliament in Cairo and I remember that Yasser Arafat was sitting in the VIP chair,” Sadat said. “I revealed my plans to visit Jerusalem and the ministers, delegates, Arafat and the newspaper editors cheered, not realizing or believing that I really intended to make the dramatic move and visit Jerusalem.”

Osama al-Bazz, a senior adviser to the president, began to scream and shout that the president had lost his mind and recommended that he be isolated for a few days of observation.

Among Israelis too, I told Sadat, there was disbelief regarding what you said. “We were sure,” I told him, “that you were issuing pronouncements regarding peace in order to divert attention from Egypt’s many problems.”

Mussa Sabari, the editor of the al-Ahbar daily told me how he sat among the VIPs in the parliament and heard Sadat speak of visiting Israel and decided, together with his two fellow editors at al-Ahram and al-Gomhuria, to omit mentioning the plan to visit Israel from news reports. Not a word of it was reported.

“We too, in the Israeli media,” I told Sadat, “did not attribute any special importance to your message. We did not recognize that it was a historic moment, and we did not publish it."

“So what are you worth as journalists?” Sadat replied. “The following day, upon seeing that the Egyptian media failed to print anything regarding my intention to visit Israel, I called the editors who heard my speech and told them off.”

I attended a secret conference at the Van Leer Institute in November of 1977, three days before Sadat’s visit to Jerusalem. The institute’s director invited me, along with intelligence officials and Egypt experts in academia, to a long discussion regarding the objective of Sadat. Why would he suddenly decide to break away from the Russian bear hug, move to the American side and suddenly declare his intention to visit Israel?

Nobody there believed that the visit would result in a genuine peace agreement. The Arabist historians pointed to the bread riots in Egypt that year after the authorities allowed for the bread and pita to be sold at a smaller size to reduce expenses. The military men spoke about what Sadat did to the Russians and stressed that they could not find any evidence that the Americans had no believed that Sadat rally intended to fulfill his pledge and achieve a peace agreement with Israel.

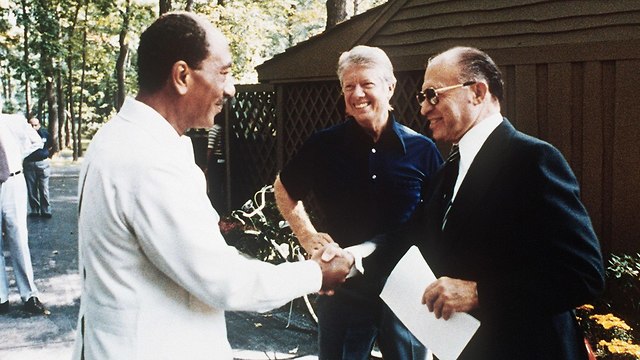

The meetings in Morocco between Dayan and Tuhami were kept under wraps, both in Israel and Egypt. Only prime minister Menachem Begin was sure that something unique was happening in Cairo. Begin directed his staff to ensure the continued secrecy of the Morocco meetings and went out to meet Sadat.

“Imagine, none of my men wished to join me on the visit,” Sadat told me. He left his deputy, Hosni Mubarak, responsible for internal security. On the return journey, the flight plan was changed and they landed in Cairo instead of Alexandria. Sadat was twice greeted by excited crowds. “As in Jerusalem, thus I was greeted with mass joy in Cairo,” he said.

The first round of talks at the Mena House Hotel were intended to bring together the two delegations. They exchanged gifts, went to a night club to see the famed belly dancer Fifi Abdou, a native of Sadat’s village, ate together around the huge wooden tables and conducted private talks. The journalists took advantage of any opportunity. It was not simple to merely leave the hotel and take a cab to central Cairo.

We visited the Khan al Khalili Market. A colorful, dynamic place, full of statues of mythological figures from the Valley of the Kings in Luxor, small hand crafts made with coarse hands, miniature statues of the Sphinx and Pyramids, and fake perfume bottles.

Beyond the market, we visited the Al-Azhar Mosque. At night a large group of journalists went to the Hilton Hotel on the outskirts of Cairo. All at once, peace was forgotten in favor of casino gambling; one playing the roulette, the other exchanging currencies or receiving prize money.

The souvenirs were delightful — a gold pendant of Queen Nefertiti was sold in dozens of different sizes and prices, according to one’s ability to bargain; small, painted wall rugs, and three handmade birds that are in my living room to this day. All the souvenirs were snatched up and the books I was asked to lend were never returned.

Relations will remain cold

My interview with Sadat caught me by surprise and owing to the excitement, I failed to notice how one of the residence’s staff members placed his own recording device alongside my own and released the interview to the Cairo media. The response was immediate: In Israel, the celebratory promises of the Egyptian president were welcomed with open arms.

In Egypt on the other hand, the picture was more complex. The masses who celebrated Sadat’s return from Jerusalem pounced upon the newspapers and welcomed the peace deal. They envisioned the deal bringing economic cooperation and prosperity to Egypt.

However, a large group of academics and senior media people despised the fact that Sadat failed to even mention the Palestinian issue. the intellectuals did not give up and attacked the president and the peace initiative for months afterward. Two years later, Sadat imprisoned them for “Harassment of decisions and interference in state affairs.” Only after his assassination during a Yom Kippur War victory march and was replaced by Mubarak, were they freed from prison but their aversion to the peace deal remained.

We felt so comfortable in Cairo on our first visit that we decided on a long day of sightseeing in the city. We began at the Egyptian Museum, continued to the great synagogue, had coffee at the spot my parents met when they were serving in the British military and purchased boxes of locally made chocolate as a special gift for my parents in Haifa.

Then we found ourselves outside of the veteran Madbouly Bookshop central Cairo. I will never forget how the publisher and store owner, Ayman Madbouly, greeted me with a huge smile. I immediately informed him that we were from Israel and I was looking for new novels and special books in Arabic.

He gave a small, cunning smile and led me to the Israel shelf where he showed me the collection: the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a book of caricatures about the "greedy Jew," Israeli biographies translated into Arabic with a vulgar introduction, and another book whose name I cannot recall but whose cover I remember very well: a drawing of an ugly Jewish figure lying on the ground and above him, men dressed in Arab garb, threatening his life.

“This new reality between us will not go smoothly,” Madbouly told me. “The Egyptian people do not like you. Sadat and Begin can sign as many agreements as they wish but my people will not follow them. You will see that relations will remain cold and distant.”