Raed Saleh was 5 years old when his family left their Palestinian village in the West Bank for a better life in Germany. Now 41, the Muslim has become one of Berlin's top politicians and is spearheading efforts to rebuild a synagogue in the German capital that was destroyed by the Nazis 80 years ago.

What may sound utopian in parts of the world where hostilities between Muslims and Jews run high has become a reality in Berlin: Jews, Muslims and Christians have joined forces to rebuild what used to be one of the city's biggest synagogues.

Co-existence isn't always easy in Berlin, either, but with the blessing of people like Saleh, who heads Berlin's Social Democrats and is a lawmaker in the city's government, the interfaith effort may come to fruition in a few years.

"In the past, Berlin tore down the wall between west and east," Saleh said during a recent visit to the synagogue. "Today, we must tear down the walls of hatred."

"The growing anti-Semitism and hostility toward Muslims, the growing intolerance toward each other -- this cannot go on," Saleh said.

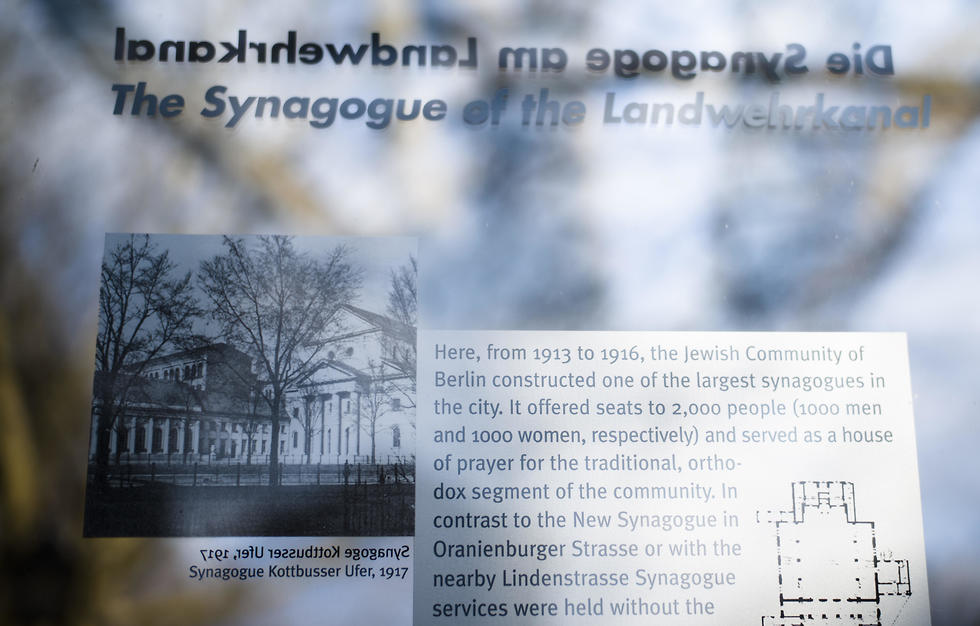

The Fraenkelufer synagogue was opened as an Orthodox house of prayer in 1916 and held 2,000 worshippers. Before the Third Reich, Germany's flourishing Jewish community counted about 560,000 people and was known for its cultural and intellectual prominence. In 1938, however, five years after the Nazis had come to power in Germany, mobs destroyed parts of the building during the Night of Broken Glass, or Kristallnacht, in which synagogues, Jewish stores and homes were vandalized across the country. In the Holocaust that followed, the Nazis and their henchmen murdered 6 million Jews across Europe.

Today, only a side wing of the building, known as the youth synagogue, remains in the middle of what has become a mostly Arab and Turkish immigrant district dotted with mosques, tea houses and kebab stands.

Nonetheless, the small synagogue has attracted a growing number of young Jewish families who have moved to the German capital in recent years from Israel, the United States, the former Soviet Union, South America and Australia.

Saleh said he met up with some of the temple's members over hummus and falafel a while back and asked them how he could help support the growing community.

The answer was clear: they asked for more space.

"When we have bigger events and celebrations, this space is bursting at the seams, it's very quickly getting very tight," said Jonathan Marcus, 38, who is a fifth-generation German member of the Fraenkelufer synagogue. He said there's also a need for additional prayer space, study rooms and a kindergarten.

Saleh promised to turn his words into action last year and now chairs a diverse board of trustees including Jews, Christians and Muslims who seek to raise the estimated 24 million euros ($27.3 million) needed to rebuild the temple's main building, which before the war was a white neo-classical structure fronted by columns.

There are no architectural blueprints yet, but many enthusiastic supporters who hope to collect enough donations to break the ground five years from now.

One of them, Nirit Bialer, a 40-year-old Israeli business development manager who moved to Germany 13 years ago, said she can't wait for her dreams of a cultural center within the synagogue to become real.

"I think it's great that Berlin enables us to work together -- people of different faiths, of different backgrounds," Bialer said before attending a prayer service on the eve of the Purim holiday inside the synagogue's somewhat cramped prayer room. "The fact that Raed Saleh is Palestinian by roots is a non-issue ... for me he is a Berliner."

So far, Saleh says reactions to the project have been overwhelmingly positive. Even some Muslim communities vowed to collect money for the synagogue in their mosques after Friday prayers.

"In the end this synagogue is more than just a synagogue: It's a sign for togetherness of religions, cultures and traditions," Saleh said.