Besides the day her father was pressed into the forced labor squads, the clandestine missions under the nose of the Nazis, the traumatic separation from her mother, the overcrowding on the train, the bombings, hunger, uncertainty and fear, after the dysentery at Bergen Belsen Concentration Camp —after all of the above, Daisy Hefner reached Auschwitz. It was supposed to be a sweet moment. After all, her life was spared. But Hefner, 90, primarily remembers the cold.

She was a girl of 15, experienced in hardship and tribulations, who escaped Nazi-occupied Hungary. None of that changed the fact that it was mid-December and it was freezing. Snow covered the city of Caux, 1,000 meters high in the Swiss Alps, and all Hefner received to protect herself from the cold was a blanket.

"Our toes were black from frostbite," she says with a Hungarian accent. The fact that she had survived the difficult phase of her journey mattered less to her than the need to find warmth.

Hefner probably does not recall how, amidst the chaos during the disembarking process, how her personal information was jotted down in blue ink as: Yehudit Tauzski, 10.11.1930, Budapest; student. She made up the birthdate and name as it was the name on the slip of paper she received that allowed her to board the Kastner train. But Hefner's life story is more than real.

75 years after being rescued from the claws of the Nazis, the name of the retired teacher from Kibbutz Givat Brenner and great-grandmother of four, appears on two newly discovered lists of survivors, passengers on the Kastner train that brought them to safe haven in Switzerland.

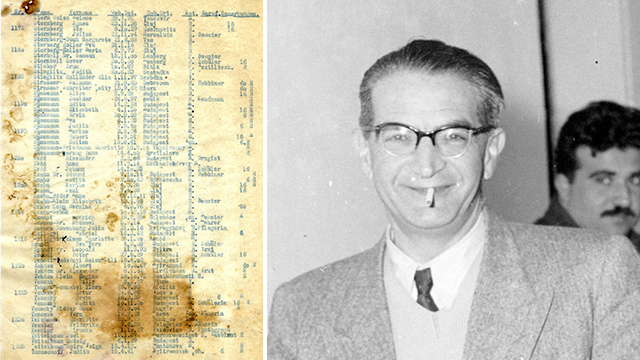

Unlike other, previously publicized lists of the train's passengers, these two lists describe the end of the harrowing journey outside of Nazi-occupied Europe. The lists were located in the Central Archives for the History of the Jewish People at the National Library and will be made available for public viewing, online, this week in honor of Holocaust Remembrance Day.

The lists were delivered to the archives 30 years ago by Rabbi David Moshe Rosen, the chief rabbi of Romania during the Communist period. Although the items received underwent preliminary cataloging, the historical worth of the documents escaped the eyes of the archivists and their actual value was only recently discovered due to a research project utilizing the archives.

The list of people on the "Kastner train," which ferried 1,670 Hungarian Jews to safety, has been published before, but it was drawn up when the train left Hungary, or during its stop at Bergen Belsen.

The uniqueness of these new lists is that they were compiled at the end of the rescue operation. For example, the lists reveal that when the train arrived in Switzerland in December of 1944, there were 20 less people aboard then previously assumed. For some reason or another, those 20 individuals failed to make the journey from Bergen Belsen to safety.

Two of the new lists consist of 1,672 names, fewer than the commonly assumed sum. However, several of those who remained in Bergen Belsen and did not continue on to Switzerland did manage to nevertheless survive the war.

The lists provide a new perspective in understanding one of the biggest, most complicated and controversial rescue operations that took place in Nazi occupied Europe and in Jewish history in general.

Daisy Hefner was born in 1929 in Budapest. She was an only child to artistic parents. Her father had a dance and acrobatic studio and her mother had a clothing store that also supplied costumes for the theatre. They were Jews, but most importantly they were Hungarians —her father fought in the First world War, she studied at a Protestant school and the family was indifferent to Zionism and rarely celebrated Jewish holidays.

"I recall that on Rosh Hashana we would go visit my grandparents and once we celebrated Passover, that is all," says Daisy. "We knew we were Jews, but religion did not play a role in our lives. I never encountered anti-Semitism."

But once the Second World War broke out and the destruction of European Jewry began, rumors regarding the Nazis actions reached Hungary (then still free). "We did not have a radio or newspapers, but we felt from the atmosphere in the house that something big was happening," she said. As the war progressed and began influencing events in Hungary, that felling grew. Jewish refugees from Germany and Poland began trickling in to Hungary and the Hefner family even hosted a few of them. "My father was inducted into forced labor squads and I don’t know how my mother obtained food, but we managed."

Following in the footsteps of her cousin, she joined the Zionist youth movement Habonim Dror and would carry out secret missions to provide food and supplies to Jewish refugees in Hungary. "I was not a hero, rather a curious girl who suddenly felt very important," she says modestly. "At times it was very scary, travelling by train to the mountains to bring food in a backpack to Polish Jews. Apparently, I was a very brazen and curious girl." Her boldness and curiosity would soon help her survive.

The German occupation of Hungary in March 1944 brought with it decrees targeting the Jews who were subject to curfews and had to wear a yellow tag. A fellow member of Habonim provided her with a "ticket" to safety.

Several hundred Hungarian Jews received such a "ticket" that allowed them passage on the "Kastner train" which left Budapest in June 1944.

Hefner met other Jews, many frightened and confused, at the predetermined meeting place at the outskirts of the city. There was a rumor that they would travel to the Land of Israel via Spain; others spoke of Auschwitz, a notorious location they had heard stories of.

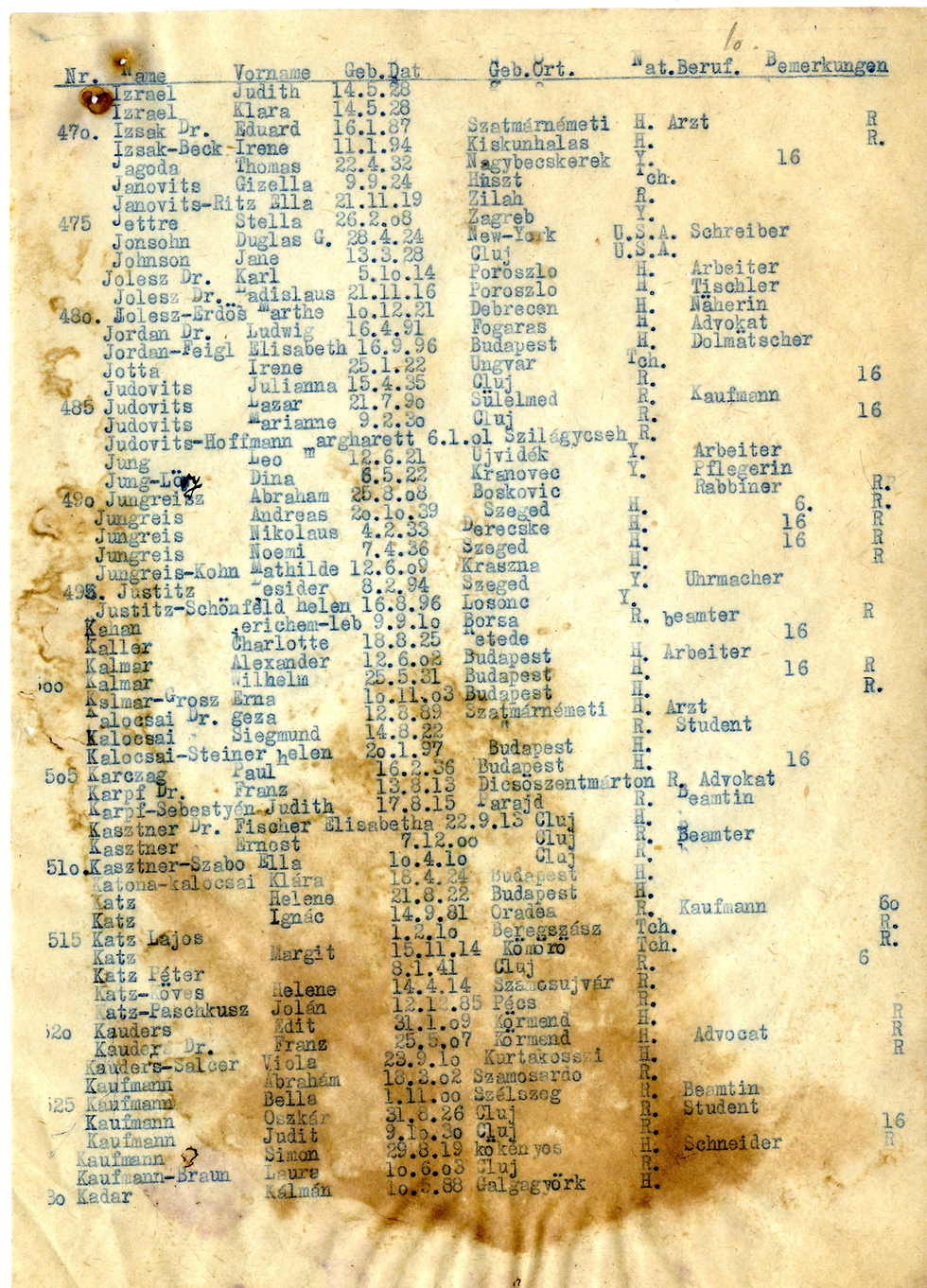

Dr Israel Kastner was raised in an affluent Jewish family and he was a prominent Zionist activist in Hungary. He was among the founders of the Aid and Rescue Committee in Budapest which assisted Jewish refugees. Following the Nazi occupation, the committee, headed by Kastner, began negotiations with the Nazi commander charged with Jewish affairs Adolf Eichmann to transport Jews to countries outside of the Nazi occupation zone in exchange for money and goods.

Kastner ultimately managed to convince the Germans to allow several hundred Jews to escape Hungary. In June 1944, a train left Budapest with 1,684 Jews onboard. The train made a stop at the Bergen Belsen concentration camp in Germany where its passengers waited as negotiations continued. In December the train finally left for safety in neutral Switzerland.

Hefner describes the experience as a chaotic and confusing one. The passengers were crammed into the crowded train cars and were uncertain of their fate as they slowly made their way West, through territory under allied bombardment as well Nazi bureaucracy.

Hefner contracted dysentery and was barely conscious during the first few weeks in Bergen Belsen. Even after reaching safety in Switzerland she describes the ordeal as a nightmare: they were put up in an abandoned hotel without heating, high up in the Alps and she mainly remembers the cold they were subject to.

In 1949 Hefner immigrated to the young State of Israel and settled in Kibbutz Givat Brenner. Her mother also survived and made her way to Israel as well. Her father on the other hand, perished during the war.

In 1952, a journalist by the name of Malkiel Greenwald accused Dr Kastner of preparing the ground for the destruction of Hungarian Jewry by the Nazis and of plundering their property. He described the Kastner train as carrying "well connected" individuals, including Kastner's own family.

Kastner sued Greenwald for libel leading to the famous "Kastner trial" which opened a pandora's box that has yet to fully settle. The trail shook the foundations of Israeli society and in his verdict, judge Binyamin Halevy wrote that "Kastner had sold his soul to the devil."

The narrative that emerged following the trial was that Kastner personally chose which Jews would be saved from the Nazis and did so at the expense of the rest of Hungarian Jewry, for personal gain while cooperating with the Nazis. In 1957, while the verdict was under appeal, Kastner was murdered outside of his home in Tel Aviv; it was Israel's first political murder.

Shortly before his death, Kastner penned his thoughts on the matter citing the complexity surrounding the question of which Jews ought to be saved and who would be left behind. He wrote that at least children, especially non-orphans, and those Jews who devoted their lives to public service ought to be saved, along with their wives.

Many of those recued by Kastner remain in contact with each other and stubbornly defend him, arguing that he had the brazenness and courage to approach Eichmann and take action.

"He did not choose me to be on the train, he did not know me," says Hefner, "he gave the "tickets" to the youth movement and religious leaders (like the Rebbe of Satmar), as well as many intellectuals and wealthy individuals whose money went to the rescue effort."

"I was never ashamed of being a 'Kastner survivor,'" says Prof. Victor Hernik. "Kastner saved me, I was lucky. I had no special right to board that train, but nor did I have any less right than other children."

Hernik, who is now professor emeritus of mathematics at Haifa University, was five when he boarded the Kastner train with his parents. His father was a Zionist activist, which gained him the "ticket" to escape with his family from the Kluj Ghetto while most of its inhabitants perished in Auschwitz.

"I am here today because of Kastner," he says. "Some people criticize him saying he should have acted differently. But if such a person had lived in Budapest at that time and had to make the decisions that Kastner made, they would understand the significance and responsibility. I don’t think Kastner could have acted differently."

Every year, around the time of Holocaust Remembrance Day, Kastner train survivors gather outside Kastner's home in Tel Aviv and light a candle in his memory. They feel that they have an obligation to cleanse his name of the accusations he faced.

In the words of Dr. Yohai Ben-Gedalia, director of the Central Archive for the History of the Jewish People at the National Library, "Much of the talk surrounding Kastner is regarding the controversy of his character and the train. The lists we have discovered do not shed new light on this matter, but rather on the survivors themselves."

When researchers looked into the addresses where the train passengers stayed in Switzerland, they discovered that they were all institutions of the Swiss Jewish community, testifying to the effort by Jewish organizations to help their brethren.