Israeli Ambassador to the United Kingdom Mark Regev spent years as Prime Minister Netanyahu’s spokesman to the foreign media before being elevated to his sensitive posting.

Ambassador Regev, who has sat for few interviews, discusses the unique responsibilities of representing the Jewish state to a major power with anti-Semitism again on an upward trajectory and a burning issue in the political landscape in an exclusive conversation at the London Embassy.

Mr. Ambassador, much has been written and said about the rise of anti-Semitism globally, and in particular in Great Britain. During the three years of your tenure in the UK, what have you witnessed?

There is no doubt that we have seen the rise of anti-Semitism, and it’s very sad. It’s not that long ago there was a feeling anti-Semitism was dying out.

Following the horrors of the Holocaust, people thought humanity has finally learned its lesson that the people would understand where this oldest of hatreds can lead and we would finally throw anti-Semitism into the dust bin of history where it belongs. That hasn’t happened.

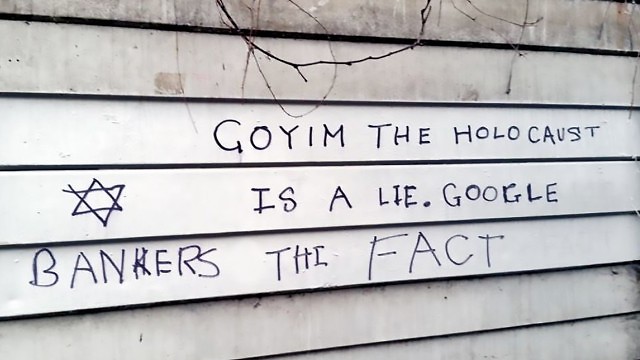

There is something about anti-Semitism; it manages to mutate and to make itself relevant for new generations. And today in Europe, if we are frank, you see old-fashioned far-right neo-Nazi type anti-Semitism.

You see (it) with the radical Islamists... and you see on the far-extreme left, you see anti-Semitism. And what unites the three of them? They’re all extremists; there is something about the political extremes that attracts anti-Semitism.

It’s possible that when you’re on the extreme and everything is so simple, everything is black and white, when you divide the world simplistically between “goodies” and “baddies,” it’s very easy to put the Jews in the “baddies.” And there is no doubt that we see, across Europe and the UK, a reemergence of anti-Semitism when many people thought this was just a relic of the past.

What do you do? How do you solve something that’s gotten out of hand?

It’s difficult. You have to fight it. And here I want to praise the UK government, which has been very, very strong in fighting anti-Semitism - both in providing moral leadership on the issue (and) in its guidelines.

I think the United Kingdom was one of the first countries in Europe to adopt the IHRA (International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance) definition of anti-Semitism, which is very important because how can you fight anti-Semitism unless you can define it?

And they’ve been, to be fair, very supportive of the Jewish community vis-à-vis what the community does to protect itself. And I know in Israel, we’ve praised the UK government for its strong stand against anti-Semitism.

There have been problems on the university campuses in particular when it comes to anti-Semitism, swastikas, chants, demonstrations. I’m sure you’ve witnessed a lot of it in speaking. What do you feel is the tool today that most benefits Israel in order to turn the clock back?

One has to find anti-Semitism and there’s a myth about anti-Semitism. It’s a very comfortable myth but it’s a myth and that is that the anti-Semites are only the uncultured, the uneducated, the unwashed, the skinheads with tattoos who never finished primary school.

It’s not true. We know from studying history that some very, very educated and important people were anti-Semitic. And that there is anti-Semitism on university campuses today in the second decade of the 21st century shouldn’t come as a shock because we know that in the previous century, many anti-Semitic movements were very popular on university campuses. So, we have to fight it. Where we see anti-Semitism, we have to fight it.

You say, Ambassador, ‘we have to fight it.’ It’s a global issue today. It begins at the top where it could be a dean of a university; it could be the head of the department. Where does one begin?

I think it’s incumbent on everyone. It’s incumbent upon Jews to fight anti-Semitism because they are the victims of it, but it’s also incumbent upon non-Jews to fight anti-Semitism. It’s often been said, it’s almost a truism, that anti-Semitism is the canary in the coal mine.

(W)hen you see anti-Semitism, always remember it’s not just about the Jews, because the fact that someone is sprouting anti-Semitic language usually it means he’s got an agenda that is dangerous for everyone. And I think we’ve seen that in modern history on numerous occasions.

Before being appointed ambassador, as adviser to Prime Minister Netanyahu, you were privy to the friction between the two nations. As ambassador in London, were you surprised or relieved at Israel’s status among the British?

Look, I’ve had a very exciting time here in Britain. We celebrated, one year into my term, 100 years of the Balfour Declaration, and we remembered Britain’s important role in providing the framework where the Jewish people could re-establish our sovereignty and independence in our historic homeland.

I mean, Balfour didn’t give the Jews the right to national self-determination. That is our natural right, that is our historic right. The importance of the Balfour Declaration, in November 1917, was that it was the first time a major global power recognized the right of the Jewish people to self-determination in our homeland. And that’s the importance.

And Balfour leads to a series of events because Balfour ultimately starts off as the unilateral declaration of a major world power. It is then accepted by the major allied powers who win the first world war: the French, the Italians, others, the Americans. And then it becomes the official policy of the international community when the League of Nations officially adopts the Balfour Declaration.

So, what started here in Britain is, in many ways, the beginning of the international support for Zionism, for the return of the Jewish people to their homeland, and for the establishment of a national home for the Jewish people.

Do you think that relationship has strengthened?

If I look at different vectors, and I look at the time I’ve been here, I see the relationship between the two governments as moving in the right direction. I see the relationship between the two countries moving in the right direction.

I’ll give you a few examples: The trade relationship between Britain and Israel is moving in the right direction. There really is positive momentum. Last year, in 2018, we had bilateral trade, 8.6 billion pounds. For Israel, Britain is our third largest export market.

First is the United States of America, then comes China, then comes Britain. Last year, if in 2018 we had 8.6 billion pounds (about $11 billion) in bilateral trade, the year before in 2017, we had 7 billion. The year before that, was 20 percent less.

In other words, we’re seeing a continuous growth in the trade between our two countries. That’s good for jobs, that’s good for prosperity in both countries.

Import/export?

Yes, that’s correct. And we were one of the first countries to sign a trade deal with the U.K. as the U.K. leaves the European Union. Up until now, we’ve traded with the United Kingdom in the framework of their membership of the European Union.

We now have the legal framework in place so that when Brexit happens, we can continue to see the trade grow between Israel and the U.K. But that’s only one factor that shows, I think, the strength of the relationship.

Our defense relationship is stronger than ever. We had in April a visit by the chief of the general staff of the British military, General Carter, the most senior British soldier in uniform. And he met with (Israel Defense Forces chief-of-staff) General Kochavi, and that was just an example of the close defense cooperation we have.

Israeli pilots will be here this year in the United Kingdom to train with the Royal Air Force, in an exercise called Cobra Warrior. That’s later this year. Israeli pilots and British pilots will be conducting joint exercises in British skies. It’s the first time it’s happening publicly.

And so, on the defense side, we see a lot of cooperation; we see that growing and that’s making people in both our countries safer.

On the political side, at the recent so-called United Nations Human Rights Council, where Israel is automatically bashed, I’m happy to tell you that Britain voted against all the Chapter 7 anti-Israel resolutions. They set an example for other countries. And that is only one manifestation of what is ultimately a very close political dialogue between our two countries.

In the three years I’ve been here, Prime Minister Netanyahu has been here three times for meetings with Prime Minister May. And maybe the icing on the cake was last year’s visit by Prince William, the Duke of Cambridge, to Israel. The first ever official visit by a senior British royal to the Jewish State and it happened just last year.

So, there is a lot that we can be proud of. There remains a lot that we need to do and one can never rest on their laurels, but today, I think I can say with confidence that U.K.-Israel relations are in a pretty good place.

Do you think that that status quo will build even if there’s a shift in elections, that Teresa May is voted out?

I don’t take anything for granted. One has to work always to make sure the relationship remains strong and robust.

The Palestinians say they won’t accept any involvement in the peace process, while it is no secret the Europeans are anxious to become first-line players. Is it possible that you could see the U.K. playing a role in terms of this process?

I think there’s an understanding among all serious people that the United States is the crucial actor here. And as we speak, people are waiting for the Americans to put something on the table. And I think everyone is waiting to see the nature of the American plan. We haven’t seen over the last few months independent European initiatives. I think the international community is very much waiting to see what the Americans are going to put on the table and the system is waiting for that to happen.

You’ve developed somewhat of a reputation for your outreach to the Muslim community, yet if you google Ambassador Mark Regev, there are many suggestions the Ambassador is pretty rough on the Islamic population. Which of the two is an accurate portrayal?

I’ve tried to do as much outreach as I can, as the Muslim community in Britain is an important community. We at the Embassy have done events together with different Muslim groups. I, at my residence every year, and will be doing it again this year, have an Iftar event where we break the Ramadan fast together.

I invite members of the Jewish community; I invite, obviously, members of the Muslim community. My goal is this: I want to show that Jews and Muslims can be friends, that we aren’t destined to be on the opposite sides of a conflict, and I think it’s possible and we have to work at it.

This year, my embassy organized for a group of British Muslim spiritual leaders, Imams, to visit Israel. That’s important. We have to work at building bridges with the Muslim community.

I’m old enough to remember when (Egyptian) President (Anwar) Sadat came to Jerusalem. We celebrated earlier this year 40 years of the peace between Israel and Egypt. And I remember he landed in Israel on a Saturday night, and on the Sunday morning, before he started his official meetings with his Israeli counterparts, he went to the mosque and he prayed and he said: ‘My religion is a religion of peace.’ And it’s important that we engage with the Muslim community and we find ways, as I said, to build bridges and understanding. I think that’s the important part of my job.

What have you learned about the relationship between the UK and Israel you didn’t know before your posting?

Every day, I learn something new. Britain’s relationship with Israel goes back, as I said before, to the Balfour Declaration, when it played an important role. We had a British mandate, yes, from the end of the First World War until the British left in May 1948.

Now it’s true, I’m not telling a state secret, when I say that we had ups and downs with the British. When the mandate ended in 1948, there were many people in Israel who thought the British had let us down, that they hadn’t fulfilled their promises to us in the Balfour Declaration and their legal obligations under the mandate.

But it’s a long relationship, it’s ongoing. Today, I’m glad to tell you that the relationship is in a good place.

On a personal note, looking back at your time as Israel’s media representative in a somewhat difficult position, what’s your greatest source of pride and what do you wish was different?

I hoped when I was the spokesman for the government to international media and I hope the same now in my current position, that I am earning my salary in a way that brings respect for my country. In other words, the Israeli taxpayers are paying me to do a job and I hope I am serving them in the best way I can, with professionalism, with diligence, and with a commitment.

Ultimately, and I believe this strongly, I don’t think I could do my job effectively unless I believed in the essential justice of Israel’s course. And I do, with my entire being, I believe in the essential justice of Israel’s course. And if I am privileged to be, in the past I was the spokesperson for the government, if today I am ambassador in the United Kingdom, that is for me not just a job; it is in many ways a vocation, it is something that I give my entire being to.

From Australia to a kibbutz to the streets of the United Kingdom, you’ve witnessed a lot of food fare. Do you have a favorite food here in Great Britain?

I’m not a big food person. I like all sorts of food. You know the British are famous for their fish and chips but walk down the street here in London and you will see food from the Middle East, food from Asia and from the Indian subcontinent.

The truth is, I like a lot of it. I like most of it. I would even say, I like it all.

What do you miss most from home?

Family, friends. I’ve got two older children I left behind in Israel. I’ve got now a granddaughter in Israel. You miss family, you miss friends. Also, as an ambassador, you’re an official, yes? An ambassador is always on duty. In Israel, I can be Mark.

Article written by Felice Friedson. Reprinted with permission from The Media Line